Notes on My Father.

Written by Yuri Varshavsky, published at “Panorama Iskusstv”, v. 11, Sovetsky Khudozhnik Publishers, 1988, pp.351-363; translated into English by Richard DeLong.

I will start out with the fact that my father belonged to a class of people who are nowadays quite rare. A member of the intelligentsia in terms of profession, interests, and personality, he nonetheless lacked systematic training. In other words, he was self-taught or, as he liked to call others like him, an “autodidact.” In 1919 Father completed third grade at a private gymnasium school in Odessa and left his parents’ home at the youthful age of thirteen, never to receive any formal education again. To put it more accurately, his education continued always and everywhere. Though he never went beyond the gymnasium basics in the hard sciences, he took to the humanities with zeal, soaking up knowledge wherever he could find it. Father said, “I never took a single test in my life.” And though a diploma-carrying expert might occasionally uncover gaps in his knowledge, the same person would, a moment later, be struck by how precisely Father was able to describe historical and literary context or give an art attribution. The very fact that Father acquired his erudition on his own, outside of school and through unconventional and at times not entirely “legitimate” means, is probably why he knew so many things which “nobody knows anymore,” as he proudly put it. The way he said this conveyed the attitude of a collector: the world of facts also has its rarities, and possessing them gives you something to boast of. The facts of history—particularly the history of culture, thoughts of great sages, famous pithy sayings, paintings, prints, poems, schools, and names—all of this Father didn’t just pick up on the fly and somehow manage to remember; this was his reality, his bread and butter, his heart and soul. Not all diletants are created equal. Father was a diletant in the sense that is closest to the original Latin word delectari—to take pleasure, joy, or delight in something. This enjoyment of culture (along with prodigious talent, of course) explains how a gymnasium dropout acquired an all but encyclopedic knowledge of the humanities.

My father’s uninterrupted, intense, and intimate relationship with the realm of culture is, I believe, where the broader secret of his personality is to be found—the “hidden engine” driving his ability to live a happy life in spite of circumstances. Two passions burned brightly in him: a passion for literature and a passion for art collecting. The highlights of his days had to do with books read and additions made to his collection. It was at these times that he felt most fully alive or, put simply, was happy. Father also derived joy from his own writing work with its nearly unbearable tension and fleeting moments of serendipity. The mundane and commonplace, on the other hand, bored him to tears. Ordinary chit-chat made him glum, and he would quickly grow despondent and even seemed to age before your eyes. But all it took was mentioning some literary pseudonym or quoting a line of poetry, and Father would spring back to life, his countenance instantly becoming more youthful as he enthusiastically joined the discussion. In the last two years of his life, Father was quite ill and often lacked the energy to leave his bed for a day or more. The only thing that could make him get up was if a collector friend dropped by to share his excitement over a lucky find or—even better—offer an interesting swap. Half an hour after getting a phone call, Father would be sitting in his office clean-shaven and with his tie on, waiting for the guest to arrive. “Resuscitators”—that’s what my mother rightfully called these guests who would bring him back to life. Father’s safeguard against the pettiness of everyday life, against squabbles, misfortunes, ailments, and old age was what people used to call “higher interests” (he liked to use this expression, which must have become part of his vocabulary while still a young lad). A lesson for us all…

My father was born in Odessa in 1906. Along with his brother, who was two years younger than him, he grew up in a well-to-do family of intellectuals. His father was a prominent local doctor, and his mother ran the household and raised their sons. After the revolution, she went to work teaching German and English at an institute in Odessa. Their house was full of books. Being surrounded with bookshelves, book spines, and bindings from an early age instilled in him a reverence for culture, books, and the writer’s profession. I still remember the beautiful reverence with which Father’s fingers would turn, then smooth down, the pages of books.

I can only vaguely remember the contents of grandfather’s home library, but my father mentioned many of his first books at different times and occasions. Travels: the great seafarers, the explorers of Central Africa, Darwin’s Beagle. The gods of Olympus, Greek kings and heroes, Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. The French Revolution with all the fierce eloquence of its leaders. The natural world: Brehm, Fabre (I have seen Fabre’s book with its blinding coloured charts which at first barely show through the wispy cigarette paper), forbidden anatomy atlases to be leafed through in secret. Novels also had much to teach about the world: Dumas, Walter Scott, Stevenson, Cooper, Thomas Mayne Reid, Jules Verne, Hugo, Dickens… But right after them in his first years at the gymnasium came Shakespeare, Goethe, Stendhal, Flaubert, Maupassant. Here’s an excerpt from a letter which miraculously survived to our day from his childhood: “Make sure you drop by Rousseau and buy La Petit Rousse (referring to Larousse’s short-form encyclopedia — Y.V.) and bring it on Sunday… Try to exchange these three books and bring four or five to the dacha.” These are the instructions eleven-year-old Seryozha gave to his father, Dr. Varshavsky. Already, one clearly sees the hallmark traits of future Sergei Petrovich as known by his friends, acquaintances, bibliophiles, and booksellers—traits of a book hunter who would dig excitedly through the stacks at used book stores, a compiler of a rare collection of reference books and monographs on Eastern and European art, an aficionado who took it upon himself to hunt down the personal library of his mate—Estonian art historian, antique collector, and bibliophile Julius Gens*—which had been carted out of Tallinn by German soldiers.

[*In the introduction to Y.N. Gens’ Notes of a Bibliophile, published in part in Almanac of a Bibliophile (issue 3, Moscow, 1976) it reads (p. 97): “Not long before Gens’ death it was unexpectedly discovered that his books had been safely returned to the USSR as a war trophy and had found their home in the Library of the Belarus SSR Academy of Sciences.” Our family remembers just how much conflict, hassle, and effort lay behind the words “it was unexpectedly discovered.” Gens’ personal library was searched out and identified through the efforts of my father and his close friend, well-known Moscow collector Igor Vasilyevich Kachurin.]

There is something else which must be brought up in our discussion of how childhood impressions may have impacted my father’s personality. In Odessa society, Dr. Varshavsky was considered to be “red.” As the expression went, he “sympathized” with the Bolsheviks and, according to family legend, even hid French sailors in his home who were trying to escape after a revolt was crushed during a crackdown in Odessa. These attitudes, which shaped Dr. Varshavsky’s choice of books and the adult conversations that were held over tea late into the evening, must have given my father his avid, unflagging interest in the history of Russian liberation thought and reverence for the knights and martyrs of the struggle against Czarist rule. Herzen, Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov (as well as Lavrov and Mikhaylovsky) were sacred names for him. He was moved by Nekrasov’s civic passion, the poem “Praying to Your Longsuffering Shadow” wrenching tears from him. To young interlocutors, such a reaction seemed excessive, even inappropriate. Is it common to meet someone who chokes up when reading a poem out of the eighth-grade textbook that every pupil is required to learn by heart in order to get a passing grade? Father’s special draw to the Peredvizhniki (“Itinerants”) likely came from the same place. Father saw in them the same endlessly appealing figures as the Men of the Sixties and the Narodniki. He worked hard on a history of the Peredvizhniki, but in the end his main remained unrealized. There shouldn’t be anything surprising or needing explanation in the commitment of a Soviet man of letters to the democratic traditions of Russian culture. In my father’s case, however, these views were not so much consciously built up as coming from the very core of his personality, from the depths of his subconscious.

***

Father was a hard worker. Back in the thirties fortune brought him together with another hard worker, Yuliy Isaakovich Rest (pen name: B. Rest), who became his inseparable friend, lifelong co-author, and alter ego. Shortly after the completion of their first major work—a popular history of the Hermitage—war broke out. Together they passed through its trials (the blockade of Leningrad, Sevastopol, the North Caucasus, the Subarctic) as naval aviation war journalists and, once released from duty in the summer of 1945, returned to Leningrad and sat down to work at their shared desk. I remember them spending months on end during the sixties and seventies working eight to ten-hour days at the desk, never resting on weekends or holidays and never cutting themselves any slack as they produced book after book about the Hermitage. In later years they always worked in my father’s study, where they would also have lunch, perching their plate on the edge of the desk or the armrest of a chair. Working in such a duo, I believe, instilled even greater discipline in these two already assiduous men who could sit still for long periods of time and were capable of uncommon self-restriction. To be clear, the above-mentioned “desk” didn’t actually exist; this was a popular metaphor for writing work rather than an actual piece of furniture. The centre of the small, book-filled study was taken up by a round Drev-Trest table that Father had purchased immediately after his discharge. A decrepit green cloth covering the surface of the table was buried beneath various collector knick-knacks. Yuliy Isaakovich would, without looking, sweep toward the centre whatever had spread out during the night—items which were near and dear to Father but of no interest whatsoever to his friend: a piece of nephrite, a walrus tooth, carved glass, a tortoise shell… Then he would perch his hand and half a sheet of writing paper on the edge of the table, his elbow and the other half of the sheet suspended in the air. Father didn’t even get that much: he made due with a piece of cardboard—half of an old folder—balanced on his knee.

At the table were two massive chairs situated at an angle to each other and upholstered in bumpy black leathercloth—also a purchase from the forties. In places the leathercloth was worn threadbare. The co-authors always took up the same positions in their chairs as they worked on a text, discussing every word and turn of speech. I caught a glimpse of parts of this process several times. It went like this. One of them proffers a phrase which, after many attempts, he has just scrawled slantwise in the margins of his scribbled-over draft. The other looks at him with an air of deep incredulity, saying nothing. This means the wording has been rejected. Approval was indicated with comments like, “Well… okay” or “That’ll do.” Father would take these words, which Yuliy Isaakovich spoke with almost squeamish condescension, with a degree of proud gratification that he tried unsuccessfully to hide. Yuliy Isaakovich, I think, also felt something similar when Father accepted one of his suggestions with the words, “Well now… let’s try that” or “Maybe…” In the evenings I would call Father up and ask how their work was going. He would answer contentedly, “We wrote a page” or, more often, “We wrote a paragraph.”

Many people, myself included, consider Varshavsky and Rest’s greatest literary achievement to be the book Ordeal of the Hermitage, published in 1965 and later twice reprinted. The book was lauded by the press and precipitated a flood of readers’ letters, one of which I would like to quote because of how deeply it touched the authors. This letter, dated September 14, 1966 (it came just in time for Father’s sixtieth birthday), was typed on a letterhead of the Tashkent Astronomical Observatory and signed by V.P. Scheglov, director of the Astronomical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan. “Leningrad. Hermitage. To S.P. Varshavsky and Y.I. Rest. I just read your marvellous book, Ordeal of the Hermitage. I cannot hide my delight with your work, which not only conveys the hard facts but is permeated with the pronounced sense of ethics of deeply committed scholars. With this in mind, I recommend your book to every researcher regardless of their field of specialization… Health and happiness to all the heroes of your book who are yet living, and eternal glory to the fallen!” Many letters express the same idea in different words: this book about the blockade years of the Hermitage is a book about the intelligentsia’s courage and heroism during the country-wide war with Fascism. Father’s veneration for culture gave rise to a similar attitude towards the intelligentsia. The authors’ shared reverence for those who selflessly stepped forward to protect cultural heritage permeated their work and resonated deeply with readers. “The intelligentsia is a force to be reckoned with,” Father liked to say. [SV: I think it is more like ‘Intelligentsia is power’ like ‘knowledge is power’— from the Latin ‘Scientia potentia est’]. These words indicated a complete rejection of popular notions of intellectuals as complacent, fragile, and helpless. Culture is one of the powerful life-giving forces that ensure mankind’s immortality, one of life’s clinching arguments in its never-ending debate with non-existence. Is it any wonder that belonging to a cultural tradition and actively helping to augment that tradition and pass it along the historical chain of generations can be a source of indomitable inner strength? Father’s words, I believe, also expressed his special feelings for the moral heritage of 19th-century Russian intelligentsia with its spirit of self-sacrifice. Ordeal of the Hermitage also spurs reflection on the kind of bravery which one might not associate with the intelligentsia but which, in a certain sense, is actually its part and parcel.

***

As a collector, Father was primarily interested in graphics (Japanese woodblock prints and European etchings and lithography) and in Japanese and Chinese arts and crafts. What he accomplished in each of these fields was substantial. Where and how did Father manage to get his hands on so many first-rate rare works of art during the three post-war decades? I cannot even begin to tell how he did it. As Father showed off each latest acquisition, he would describe in vivid detail how it had all transpired: from whom he had obtained an album of Daumier’s lithographs and what he had traded it for, where he had picked up a particular item specifically for the purpose of seducing the owner of the album, what unbelievable coincidences had led him to this big bronze Putai—the god of prosperity—with his round belly and sagging earlobes… These stories—dramatic, instructive, and hilarious—he gladly repeated to everyone who would listen. He had planned to write them down, but never found the time. To my chagrin, I myself cannot recall most of the details. And retold approximately, these short novellas lose all their charm. So I will give a kind of synopsis. On the backs of most of Father’s etchings, which I am looking at now, are the faded stamps of used book stores in Leningrad, Moscow, and Tallinn. Like fastidiously preserved consignment store labels, these stamps belong to those bygone days when the used book and antique market was flooded with such items and there was little demand for any of it. Sometimes there were “wholesale” purchases as well—when collections of older-generation collectors were sold off by their inheritors. The third source was other collectors and included exciting swaps and crafty manoeuvring. Judging what cost what in these exchanges is next to impossible. I’ll try to construct a kind of typical example of how things usually transpired based on countless cases of a similar type. Let’s suppose, for instance, that my father is trying to hunt down small albums of Hokusai’s woodblock prints—manga. We’ll imagine that in exchange for one of these books he gave a collector friend who was interested in the Russian 19th century a miniature portrait of an unknown young woman with a low-necked dress and hairdo from the period of Alexander’s reign. The friend had caught a glimpse of this item at Father’s place and had purchased a Hokusai album he had happened across specifically to trade for the portrait, knowing that Father would not be able to pass up the offer. But how much had he paid for the album—ten rubles or a hundred? Or even more? In other words, what was the actual cost of the delightful miniature that he is now carrying home after impatiently finishing up the deal? And why is he in such a hurry? He is hurrying back to his reference books and catalogues. He can’t wait to find out the name of the unknown woman and test the hypothesis which has been brewing in the back of his mind. What do these black curls on the woman’s temples remind him of? And the wide blue sash wrapped snugly beneath her bosom? And what if he is right and it really is… herself? And if his sixth sense didn’t fail him, tomorrow he will call up Sergei Petrovich and nonchalantly ask, “Do you know whose portrait you gave me yesterday?” But that is tomorrow, and nobody knows yet what will happen… Meanwhile, Father is enjoying Hokusai. The print quality is faultless. Could it have been done during the author’s lifetime? The paper is extremely thin, and the pale pink hue has no hint of yellow. Unfortunately, there is no publisher’s imprint… He lovingly leafs through the album well past midnight. Tomorrow Father will tell us that he got the album “for next to nothing.” He had obtained the pretty, but essentially mediocre miniature (and a chipped one at that) a year back as a kind of bonus within a larger exchange. He may have just as well not received it. Pure happenstance! And so both partners emerge triumphant, each having filled out his collection with the desired object which, after years of roaming, has finally come home. What’s more, each collector is thrilled to have gotten such an amazing deal. But let’s not be shocked that two elderly men with years of experience can be so naive. Yet more shocking is that, paradoxical though it may seem, both of them are right. If you think about it, a higher truth emerges out of all these mercantile miracles—trades where it’s impossible to determine what cost what. It is simply this: attaching a monetary equivalent to works of art is, in essence, futile. However, this only becomes self-evident later, when a private collection is transferred to the public domain. At that moment artwork is finally freed from all attachment to price, which is seen for the foreign, irrelevant, and illusory concept it is. The purification process first begun by private collectors is at last complete, forever.

When asked for the secret to his extraordinary success as a collector, Father would answer, “stubbornness and consistency.” [SV: A citation from Dostoevsky’s novel “The Adolescent”]. Every morning at five to eleven, with the punctuality of someone showing up for work, Father and several other regulars would be standing on the steps of the antique shop on Nevsky. He always walked there from Liteyny, where the used book stores opened an hour earlier. Here he would take a close look at all the new arrivals, exchange greetings, have a bit of friendly banter, and sometimes make a purchase. Around 1970 his route was extended when a second Bronze antique shop opened on Sadovaya. At 11:30 or 11:40 Father would be at its doors. A good friend of Father’s, well-known antique collector B.C. Chernyak, who had served for years as head engineer at the Hermitage, died of a sudden heart attack while walking between these two stores. Though he was deeply saddened by the news of his friend’s passing, Father nonetheless remarked: “A wonderful death. A collector’s death.” Besides admiration, there was a note of envy in his voice. This was probably the only time Father ever envied anyone. From Bronze Father would hurry home; he needed time to rest and have a bite to eat before getting down to work with his punctual friend Rest, who would ring the doorbell at two o’clock sharp. Now these two men of letters began their workday, which lasted until ten or eleven in the evening.

Of course, it wasn’t every day that Father made a purchase. But even if we assume that these daily visits produced results at least ten times a month, that would amount to roughly one hundred acquisitions a year, not counting the two months Father always spent out of town. Hence, in the ten years preceding his severe heart attack in 1976 (after which he had to relax his methodical approach), Father’s collection may have grown by one thousand items in this way alone. Such is the result of perfectionism and discipline—”stubbornness and consistency.” But somethings things happened differently. During “breathers” in between books, Father’s collector side would come to the fore. No longer content with his well-travelled routes to the doorsteps of commission stores, he would set out on a vigorous open-ended search. When working in the library and archives in preparation for his next book, Father could keep a looser schedule and make time to meet with collector colleagues or with the owners of this or that item of interest. Father was methodical, tireless, and swift to act if something showed up somewhere, but that wasn’t it. He also possessed an uncanny eye, unfailing taste, and a quick mind. I can easily imagine Father feigning indifference while the shopper next to him at the counter of the antique shop curiously examines a mysterious object (could it be the handle of a fruit knife?), all the while thinking, “will he take it or not?” He didn’t take it! Now Father becomes the owner of yet another item of this type, made out of blackened steel barely touched with hammered gold and portraying a dragonfly, spider, and several bamboo shoots. It is, in fact, a knife handle—just not a fruit knife. This miniature knife (“kozuka”) was a standard part of every samurai’s equipment and was mounted in a special pocket on the scabbard of his main fighting sword. (Father would put on a ferocious face as he told guests in what situations and for what need a samurai would take out this little knife during combat. He spared no grotesque detail. I will leave the story out.) In this same way Father acquired one of his favourite items—a concretion of intricately twisted stalks of tender-milky jade which immediately caught your attention among the trinkets cluttering his desktop. Furtively slipping a nitroglycerine tablet under his tongue, Father watched another collector—an acquaintance of his who had entered the store more boisterously than he had and had beaten him to the counter—turn an odd little object around and around in his hands. Finally, shrugging his shoulders one last time, the other collector set the item down on the display glass and walked off. “Write it up please,” was all Father could say, exhausted by the wait and barely able to exhale. Several minutes later, while still in the store, the two run into each other again. “So did you buy that flower?” “It’s not a flower, it’s the Buddha’s hand!” Father tells his hapless colleague. The item was a rarity among rarities… Someone might frown and say, “Sergey Petrovich dealt inequitably.” To them I would answer: passion is passion.

Father’s broad range of interests, artistic sense, and appetite for risk were self-evident and certainly played their part, but even a comprehensive list of his accomplishments—or those of any other collector of his caliber—would still be missing the most important thing. Anything of real import in a person’s life, be it passion, skill, or inspiration, always contains an element of mystery. No matter how far intellect reaches in its analysis of these expressions of human nature, something (and is it not the most important thing?) always remains inaccessible to it. Father had the collecting talent. He was a man possessed by the collector’s passion. He was unbelievably lucky. Almost inexplicably, “the ball comes to the player.”

Father loved every item in his collections. He loved to bring them home, loved being among them, loved showing them off. He remembered where every little trinket came from and would hold onto commission store labels for decades. Some of these labels—the ones with the most evocative descriptions of works of arts—he kept at hand. For instance (1959): “White marble Buddha, 300 mm in height, 20% worn.” After arriving home with a new purchase, he would immediately begin going through monographs, reference books, and museum catalogues. Identifying the trademark on the bottom of a maiolica vessel, reading the craftsman’s name hidden away in a nook of an engraving, translating a phrase etched on a blade—these were new joys which followed after the joy of the find and which prolonged and multiplied that joy. As he went to bed, Father would put the new item somewhere near the head of the bed or even take it to bed with him (“like a Roman patrician after a successful visit to the slave market,” mother would chuckle). Father also loved oddities. Once he swapped something for a coin with a strange appearance. He wasn’t a coin collector, but some sixth sense drew him to the coin. That evening he hunted down the exact depiction of this coin in an 18th-century French manual. The text explained that it was a Judaic-style silver coin weighing half an ounce, adding with a dispassionate textbook air that Judas would have received thirty of these coins for his betrayal…

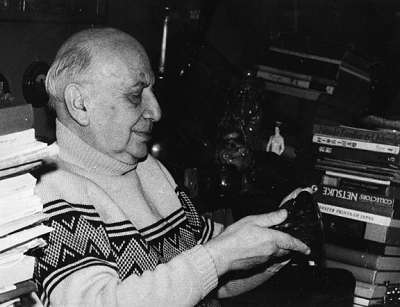

Father was drawn to the fundamentally dualistic nature of folk applied arts, which simultaneously belonged both to the base world of everyday items and to the higher world of nonmaterial culture with their dual purposes of being useful to their possessors and satisfying their aesthetic sensitivities. Father took delight in the inventiveness, craftsmanship, infinite patience, and surprising mischievousness of the artisans who created these objects, their ambition and ability to breathe life into items of everyday use. He appreciated the glossiness of these objects, which had felt hundreds or even thousands of loving touches over the course of their long lives—touches of the craftsman and his apprentice, the trader, the first owner and those who would later inherit the object, of travellers and antique collectors… Their surfaces of wood, stone, or bone were smooth in the same way that the handles of workshop tools, monks’ rosaries, amulets, and bannisters in old homes are smooth. Their projecting parts rounded, they are covered in a noble patina with accumulations of a dark substance of unknown nature filling any cavities (“condition: soiled,” the museum inventory list will later read). Father was particularly fond of “netsuke” (in our home this word was used in the feminine gender). He first came across netsuke at Gens’ home in Tallinn soon after the war. Gens’ daughter Inna Yulievna, who was there when it happened, told me that as soon as my father touched one of these little marvels with his fingers, he was unable to leave them alone till the end of the day and felt, petted, and caressed them endlessly. We saw this scene play out dozens of times, as each new netsuke elicited in Father the same excitement as the first. In the photograph accompanying this article, Father is holding one of his last finds—a precious cup made of rhinoceros horn and covered in fanciful carvings.

Among non-applied arts, Father gave special attention to graphics and print engravings. Japanese woodblock prints occupied the top position in this area of his passions. Father would gaze at the prints of Hiroshige, Utamaro, Sharaku with the same kind of tenderness with which he caressed netsuke. Old European craftsmen only occasionally found their way into Father’s collection. Among 17th-century artisans, he admired and actively sought out Callot. As for later items, he was drawn to the etchings of Duplessis-Bertaux and the architectural fantasies of Piranesi. Father had a warm place in his heart for Englishmen Rowlandson and Cruikshank and also took joy and pleasure in Gillray, Newton, and Banbury. He idolized Goya and managed to hunt down all his famous suites, though in later editions. However, the core of Father’s collection was 19th-century French graphics, beginning with the early Romantics, creators of the Bonaparteada, and ending with the Post-Impressionists, Forain, Vallotton, and Rops.

While he was still living, none of us bothered to ask him whether he saw any connection between these two branches of his collecting activities—printed graphics and arts and crafts. Now, in hindsight, the kinship between them appears almost obvious. Behind the print of any etching, one can feel the labour of the craftsman, his prowess and experience, patience and trained eye, the firmness of his hand as it generated just the right amount of force for the material’s resistance. Furthermore, the tools that an engraver and a carver hold in their hands are nearly identical. And the entire workflow for making a print engraving, with all its sophisticated tricks and complex formulas, exhibits a certain similarity to the work of an applied artist, be it carver, chiseller, or enameller. “Fecit,” “invented”—these are the words one finds next to an engraver’s signature on a copper plate, and European gunsmiths of old would etch the very same words on the barrels or locking devices of their creations.

***

In all fields of his collecting interests, Father quickly became an expert, achieving a high degree of competence. However, just like his broad knowledge of the humanities, this depth of expertise in narrow fields of art history was not the product of systematic study. Such a way of acquiring knowledge was foreign to him; instead, he developed his erudition in an entirely different manner. With his uncanny eye, Father would fish out a superior or at least noteworthy print in a used book store or in the exchange stocks of a collector friend and, upon returning home, start leafing through reference books and monographs in order to try to find out the item’s history of creation, the process by which it was made, and the convoluted story of later editions and reproductions. In the process of searching purposefully through so many authoritative manuals, he ended up reading many sources in their entirety—and probably multiple times, though never from start to finish. This was not a study for study’s sake but a zealous hunt for facts which he needed right then and there and in the greatest possible detail. Any information gleaned would lodge permanently in Father’s tenacious associative memory. Thus, each new purchase broadened his horizons and sharpened his eye. Occasionally he would have to go to the public library to find the data he needed. Most of the time, though, he already had the right books; alongside collecting, Father kept adding, year after year, to his personal library of art history reference books. I have little doubt it could compete with that of many a museum or institute. Father’s copious bookshelves often attracted specialists—art historians and historians of weaponry, furniture, costumes, etc. Volumes of art history texts which were invaluable aids in Father’s collecting activities were, however, of little interest to him as books to be read end to end. He read broadly on the subject of art, but from a different perspective, preferring artists’ memoirs, diaries, and correspondence. He was drawn not so much to the academic study of art, but to discussions around art—the thinking of the creators themselves, the responses of contemporary luminaries, societal resonance, the authorities’ reactions—everything related to the social function of art. Father’s inclination to interpret art on the backdrop of historical processes and within the cultural and societal context is what drew him to this literature—lively, polemical, paradoxical, and as yet untouched by academic iciness. He devoured all of Stasov, Chistiakov, and Kramskoi’s work, pencilled notes all over every issue of the Masters of Art on Art anthology, and read and reread the Goncourt diaries, creating for them a kind of personal index of topics of interest.

***

Earlier I mentioned Father’s avid interest in 19th-century French graphics. His favourites were Gavarni, Daumier, and Steinlen—above all Daumier, whose work brought together and most powerfully expressed everything that Father valued and admired about the extraordinarily appealing realm of French political and social caricature. Why did this realm hold such appeal for my father? I believe the roots of this feeling are to be found deep within Father’s make-up, in the fertile soil of his youthful revolutionary and romantic sentiments which, astonishingly, survived in his consciousness (and subconscious) up until his final years. The antidespotic, antibourgeois zeal of the artists of Charivari and La Caricature, their ridicule of the hypocrisy and corruptness of the official institutes of each successive monarchy or republic reflected and resonated deeply with Father’s own feelings. The targets of these satirical barbs—career politicians, the nouveau riche, pettifoggers, and executioners, with their intrigues, conceit, greed, servility to the powers that be, obsession with decorations, and frivolous amusements—were an expression of all that was base and unworthy in Father’s eyes. He held Louis-Philippe in scorn and despised Thiers. He was a passionate collector of Paris Commune caricatures, took an interest in the commune’s cultural policies, and planned to write about them. A whole drawer in his filing cabinet was taken up with notes on the subject. In Father’s view, the figure of Courbet embodied the ideal relationship between the artistic intelligentsia and the people at large who had risen up and vanquished their foes. Those who have read Varshavsky and Rest’s A Ticket for All Eternity will have noted, of course, that these interests and sentiments were closely intertwined with the subject matter of my father’s literary work. Father loved the poetry of “the damned.” [SV: Poètes maudits]. I can clearly remember his thunderous recitation of Rimbaud:

And when you are down, whimpering on your bellies,

Your sides wrung, clamouring for your money back, distracted,

The red harlot with her breasts swelling with battles

Will clench her hard fists, far removed from your stupor!

I heard these lines as a schoolboy while sitting under an enormous Steinlen poster of Marianne in a Phrygian cap calling the people to revolt. I recently donated the poster—one of the father’s favourite possessions—to the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Towards the beginning of these notes, I spoke of Father’s sympathy for the Russian Peredvizhniki. I don’t know if specialists would approve of the idea of searching for parallels between French social caricature and the genre canvases of the Peredvizhniki. However, I think this type of convergence (if only subjective) may have occurred to Father. Is there not, in fact, a certain similarity between these two very distant artistic movements? Is it not to be found in the intent focus on the typology and physiology of society, in the principled anti-academism of the artistic method, in the rejection of art as a parlour activity? In Father’s attitude towards artists and art groups this dimension—what used to be referred to as a “direction” or “school”—was seen as extremely important (and possibly inordinately so, according to current views). It might be posited that his gravitation to the Peredvizhniki and his affinity for French caricaturists both came from the same psychological source—an appreciation for the social orientation of these artists’ work.

It seems to me that diverse and seemingly unrelated passions must have certain common points of departure both in the depths of the individual’s personality and in the very nature of things themselves. Caricature is replete with mundane life details, capturing customs and tastes and meticulously recreating fashion, hairstyles and jewellery, home furnishing, tableware, horse harnessing, and artisanal implements—in short, the entire material ambience of day-to-day life. But arts and crafts—another focal point of Father’s collecting endeavors—also illuminate the history of society from the same perspective, placing at centerstage not grandiose events which changed the course of history and the way of life of the masses, but rather the way of life itself as experienced by the masses. In a sense, this may well be the most humanistic and democratic vantagepoint from which to view historical processes. Social caricature, genre art, and arts and crafts flesh out our image of the historical moment and, instead of drawing the attention of future generations to the momentous and the lofty, point to what makes it endearing, if you will. I will remind the reader that when such seemingly distant and unrelated artistic phenomena as 19th-century French print engravings and the works of Japanese engravers and carvers met in my father’s collections, it was not by any means their first meeting. When the Europeans were just coming in contact with the artistic culture of Japan in the mid-19th century, Baudelaire, an admirer of Daumier who had dedicated heartfelt verses to him, became one of its first enraptured discoverers. The Goncourt brothers, friends and biographers of Gavarni, were the first worshipers, advocates, and passionate collectors of Japanese graphics and miniature sculptures. “Japanese art is just as great an artistic tradition as Greek art,” reads a line in their diary. Next to it in the margin is a mark written in my father’s hand: “NB” (“nota bene”). The realm of culture is indivisible, just as the human soul.

***

Father passed away in September 1980 at the age of seventy-four. As he entered his eighth decade he felt a need to take stock of the fruits of his life as a collector and attend to his collections’ future. I happened across a sheet among his papers which outlined a future essay: “One cannot become a true collector arbitrarily, on someone’s recommendation, for the sake of prestige, because it’s in vogue, or for materialistic reasons.” Next came a list of real-life examples of these kinds of pseudocollectorship denoted by words that only Father could make sense of. Apparently, in the essay, he wanted to avoid speaking poorly of anyone. Then it read: “What they cannot understand is that that collectorship is not a whim, a form of entertainment, a business, or a safekeeping vault, but rather a joyous and gruelling daily labour. I’ve borne the heavy cross of collectorship on my back my whole life.” For my father, collecting was work—creative work which produced something of real value. A collection as a complete whole essentially emerges out of nothing. It consists of tens and hundreds of objects which previously lived their own (or often someone else’s) lives, lost in alien surroundings. Once together, they find themselves among their own and form a new reality. The collector is the creator of this reality. As an object merges with the collection, it is transformed, given a new life. Prior to this transformation, the item’s decorative qualities or utilitarian or religious purpose may have been at the forefront, or it may have been a family relic or something of monetary value. In its new status within the collection, however, what is most significant is its cultural, historical, and artistic value. In Father’s opinion, one of the qualities of a true, serious collector was the drive to make a collection as complete and representative as possible. Sufficient completeness, he would say, is what imparts scholarly value to any collection of even the most insignificant trinkets. This conviction was foundational to Father’s worldview as a collector, and, according to numerous experts, his collections—of netsuke, Japanese woodblock prints, and 19th-century French print engravings—fully embodied this principle. As he pondered over the future of his art collections, Father concluded that the only worthy consummation of his lifelong collecting work would be the transfer of his collections to the public domain.

First, Father offered to sell two sizable batches of French graphics to the largest museums in the country—the Hermitage and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. In 1976 a collection of one thousand two hundred lithographs—works of mostly French and some English artists from the first half of the 19th century (Géricault, Isabey senior and junior, Lami, Monnier, Gavarni, Beaumont, Decamps, Devéria, Bonington, Beuys, Harding…) came into the possession of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. The museum showed its appreciation for this valuable addition to its stock of graphics by paying homage to Father in the year of his 80th anniversary with a special exhibit of the 50 best prints. The Hermitage acquired Father’s collection of French etchings and lithographs from a later time period—in particular, first-rate print engravings of masters such as Corot, Millet, Maillol, Rodin, Sisley, Pissarro, Renoir, Manet, Cézanne, and Matisse (altogether around 300 prints). It was decided to donate two large collections at the core of Father’s eastern collections—Japanese woodblock prints and netsuke—to the Hermitage, free of charge. Through this gift Father wished to express his special appreciation for the Hermitage—the museum which he had written so much about and whose rooms his wife had so thoroughly explored, day in and day out, over her decades as a tour guide. He was also convinced that this donation would be seen as yet more proof of the key role that private collectors play in society. Father didn’t live long enough to see his plan to fruition, however, and the challenges and joys of completing it fell to our lot. In April 1984 a public ceremony was held to transfer Father’s Japanese collections to the museum. A considerable part of the collection was put on display in a temporary exhibition in the lobby of the Hermitage Theater. Hundreds of Leningrad residents—experts, art connoisseurs, friends of my father, readers, and compatriots—showed up on opening day. Over the following two months, not hundreds but thousands of attentive visitors—the new owners of Father’s collections, the thousands he had had in mind as he drafted his Act of Donation—passed in front of the exhibition stands and showcases. Many of them left emotional notes in the guestbook.

It bears mentioning that one of the reasons for such remarkable public interest in the exhibition was doubtless the fact that the traditional philosophical and ethical teachings of Japan and China and their entire cultural system, infused as it is with the Far-Eastern worldview, are currently so popular across Europe, America, and Russia. The pendulum of which Hermann Hesse spoke of has, in our days, swung powerfully to the East, and long-standing Eurocentrism has fizzled out for good. I find it telling that this shift hasn’t just occurred within the humanities; now people with a mind for technology, for electronics and automation, are also looking to the East. Perhaps they will discover in Japanese art manifestations of the national cultural characteristics that have, seemingly overnight, proven so incredibly effective in an era of scientific and technological revolution.

I would like to point out that Father envisioned the transfer of his Japanese collections to the Hermitage not as a donation under will, but as a gift to be made while he was still alive. Naturally, his imagination painted a vivid picture: a triumph of art collecting, a celebration of culture, one of his own crowning moments. Poignantly, he did not live to see this moment. But perhaps the posthumous realization of our intentions carries with it an important message and points to the possibility of winning the debate with non-existence and proving unmistakably that a person doesn’t pass away “entirely.” [SV: Allusion to Pushkin’s poems ‘André Chénier’, 1825 and ‘Monument’,1836 ].