I would like to start with an expansive citation from “Tsuba. An aesthetic study” by Kazutaro Torigoye and Robert E. Haynes [1]:

Yamasaka Kichibei [山坂吉兵] was the name of the first tsuba artist of this family. … Later members of this school shortened the name to Yamakichibei [山吉兵], still later on we see the name Yamakichi [山吉]. It would seem that the succeeding generations shortened the name to its final form. The reason for this is not clear.

The first Yamakichubei and the first Hōan are thought to have been the students of the first Nobuiye, but this is an apocryphal story. … The tsuba of Yamakichibei school show influence of the Kanayama and Owari schools to a greater degree than could be attributed to the style of Nobuiye. Thus school [Yamakichibei, SV] must be thought of as a typical school of Owari Province and any association with Nobuiye will have to be left to future research.

The working period of the first Yamasaka Kichibei is from Tenshō to Keichō eras (1575-1615), about contemporary with the second Nobuiye. The first generation lived in the Kiyosu area, but later generations lived at Nagoya in Owari Province.

Signature: The fist signed Yamasaka Kichibei in most cases, but some have just Yamakichibei. From the study of Horii we learn that the same name Shigenori has not been found on any of his work. In the Yamakichibei signature the kanji yama 山 is quite distinct, the kanji of kichi 吉 and bei 兵 are not as sharp or plain. The cutting of the kanji is shallow and with age they almost disappear.

The second generation Yamakichibei master lived in the early Edo period and moved from Kiyosu to Nagoya. He made a few larger tsuba, up to 9.1 cm in width. “We do not find any work of this size in the first generation. … He used two styles of file marks on his plate, tate-yasuri and Yamamichi-yasuri. The second signed only Yamakichibei, in three kanji, the second [kanji, SV] two being as difficult to read in this case as they are in the signature of the first generation.”

The third generation Yamakichibei is called Sakura Yamakichibei. He lived in Nagoya in the Genroku era (1688-1704). He signed Yamakichibei, but his work may be easily distinguished by his use of a koku-in (incised stamp) in the form of a cherry blossom following his signature.The characters of his signature are cut with deeper strokes making them more distinctive than the first two generations. His style varies through his use of a polished surface, ko-sukashi, or hoso-sukashi (very narrow perforations) from that of the first two generations. In some respect he should be considered as a worker in the Yagyū school style, using designs found in the first period of that school.

Later Yamakichibei tsuba: The work of the later members of this school was classified as being made by four later generations. This analysis by the late Kanamori Kazuyoshi divided the school into seven generations [sic, SV]. It does not seem that there is sufficient ground to justify the fourth to the seventh generation as distinct workers. … Besides these later works which are authentic pieces of the school we find numerous imitations in the style of the first two Yamakichibei. The best of these imitations is the work of the first and second Iwata Norisuke. There are also many poor imitations made in the late Edo age… Authentic pieces of this school, tsuba of the first two generations, are quite rare.

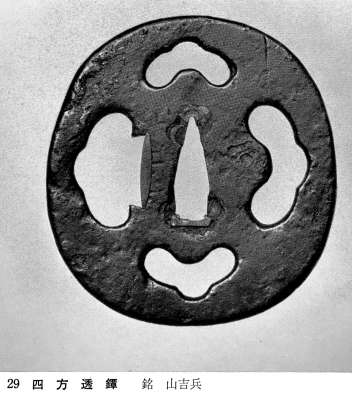

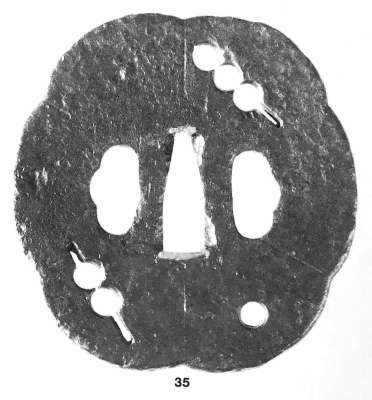

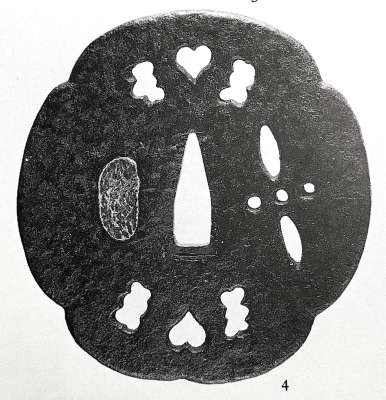

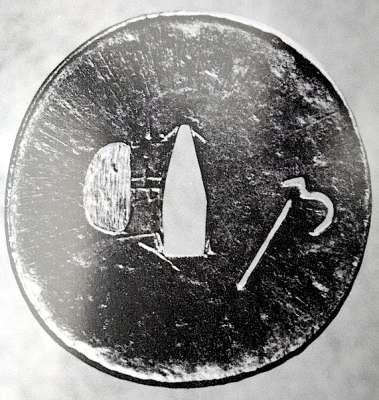

These are three photographs from the photographs from Tsuba Geijutsu-Ko by Kazutaro Torigoye [2]:

Fig. 1. Yamakichibei Shodai, p. 41. |

Fig. 2. Yamakichibei Nidai, p. 42. |

Fig. 3. Yamakichibei Nidai, p. 42. |

- Important terminology: Shodai – first generation (here, according to Steve Waszak, we distinguish O-Shodai, i.e. master himself, and Meijin Shodai, other masters of the 1st generation); Nidai – second generation masters, Sandai – third generation masters, and Kodai – unspecified later generation [4].

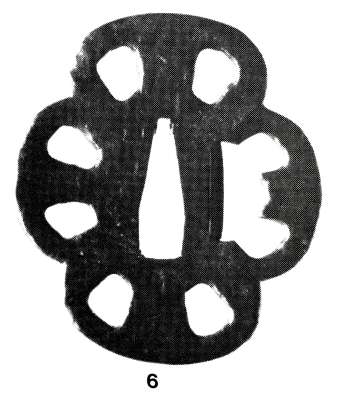

Five more examples of the first generation Yamakichibei, one allegedly signed Yamasaka Kichibei, from Tsuba no Bi [3]:

Fig. 4. Signature: Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 5. Signature: Yamasaka Kichibei. |

Fig. 6. Signature: Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 7. Signature: Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 8. Signature: Yamakichibei. |

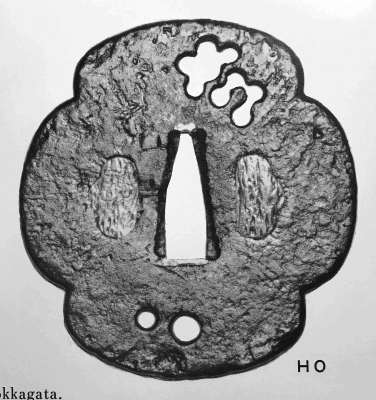

Two more specimens can be found at ‘Kodogu and tsuba’ by Kazutaro Torogoye, 1978 [5].

Fig. 9. Yamakichibei tsuba, Second. Page 207. |

Fig. 10. Yamakichibei tsuba, Second. Page 207. |

Tsuba on Fig. 9 commented: Mokkogata. Iron : Snowflakes in cut out. Tsuchime ground. Marumimi : Iron-bones, C. 1.2bu. 28bu long. Age: Early Edo. Sig., Yamakichibei.

Tsuba on Fig. 10 commented: Matsu-Mokkogata. Iron : 6 Mokkô-shape. Pine leaves and wood sorrels, in cut out. Pine cones of gold and silver suemon. Sukinokoshi-mimi : Iron-bones. C. 1 bu. 24.5bu long. Age: Early Edo. N.B. Nice work. Sig., Yamakichibei.

Syntax and punctuation retained as in the original. Both tsuba from the collection of Hiroshi Okabe.

The next tsuba is from Sir Arthur H. Church collection [6]:

Fig. 11. Yamakichi from Arthur Church Collection, p. 18.

Iron, mokko form. Irregular surface with 8 irregular piercings. Signed: Yamakichi.

Tsuba Kanshoki by Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975 [30] provides 8 examples, on pages 74-77:

Fig. 12. Yamakichibei Tsuba, First. |

Fig. 13. Yamakichibei Tsuba, First. |

Fig. 14. Yamakichibei Tsuba, First. |

Fig. 15. Yamakichibei Tsuba, Second. |

Fig. 16. Yamakichibei Tsuba, Second. |

Fig. 17. Yamakichibei Tsuba, Second. |

Fig. 18. Yamakichibei Tsuba, Second. |

Fig. 19. Yamakichibei Tsuba, Second. |

Fig. 12 = Fig. 1: Yamakichibei tsuba. First. Signed. Iron : Wheel & mushroom, open. Iron bones. Kakumimi : C. 1. 4 bu. Age : Momoyama.

Fig. 13: Yamakichibei tsuba. First. Signed. Yamakichibei. Iron : Many small sukashi resemble to Hôjutsuba. Unevenness : C. namite. Age : Momoyama.

Fig. 14: Yamakichibei tsuba. First. Signed. Yamakichibei. Iron : Kiku petal shape. Gamahada. Marumimi : 1. 1 bu. Age: Late Momoyama. Sup. – “Gamahada” means toad’s skin.

Fig. 15 = Fig. 3: Yamakichibei tsuba. Second. Signed. Iron : Amidayasuri. Iron bones. Kakumimi : C. 1. 2 bu. Age : Early Edo.

Fig. 16: Yamakichibei tsuba. Second. Yamakichibei. Iron : Two whirls of compasses, buried with lead. Kakumimi : C. 1. 5 bu. Age : Early Edo.

Fig. 17: Yamakichibei tsuba. Second. Signed. Iron : Dragonfly & wheel. Yamamichi yasuri. (mountain path-like-chisel.) Marumimi : C. 1.3 bu. Age : Early Edo.

Fig. 18 = Fig. 2: Yamakichibei tsuba. Second. Signed. Iron : Wagon, cut down. Sun-shine-like chisel on the ground. Iron bones. Kakumimi : C. 1. 1 bu. Age : Early Edo. Sup.- Dâi-shô tsuba.

Fig. 19: Yamakichibei tsuba. Signed.

[SV: Syntax and punctuation of the original retained].

Historical travel into the woods of tsubology provided us with the following information:

1902: Shinkichi Hara in his ‘Die Meister der japanischen Schwertzierathen’ [27] states:

Yamakichi: Provinz Owari. Bekannter Meister eiserner Stichblatter. Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts. [Well-known master of iron forging. End of the 16th century.]

Kichibei: Identisch mit Kichibei (Yama)

Kichibei Yama, Provinz Owari. Sohn des Yamakichi; hervorragender Meister eiserner Stichblatter. Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts. [Son of Yamakichi; excellent master of iron forging. Early 17th century.]

1904: Gustav Jacoby [31]: None.

1908: In the Okabe-Kakuya’s book ‘Japanese Sword Guards’ [28], on page 70 we find section”Yamakichi Style”:

“Yamakichi was a native of Owari province who during the middle of the sixteenth century made thin strong guards with small perforations. … Yamakichibei was a pupil of the first Yamakichi whose skillfully tempered iron shows a curiously grained surface produced by a special method of filing sometimes in parallel and sometimes in radiating lines. The shape of his guards was quite varied. He worked during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century”.

1910: The same understanding of the relations between Yamakichi and Yamakichibei was copied by Comte de Tressan in his article “L’évolution de la garde de sabre japonaise” [29]. Basically, on page 19 count simply translated the above mentioned Okabe-Kakuya’s paragraph, from English to French.

None in the J.C. Hawkshaw Collection, 1910 [8]. Owari school is not mentioned there at all. Nothing in the G. H. Naunton Collection, 1912 [9] either.

1914: Behrens Collection [7] : 1018 (no picture): Iron, conventional perforations, signed Yamakichibei. Ex-Fukushima Collection (Osaka).

1916: In ‘Japanese art and handicraft’ by Joly and Tomita [10] on page 110 in section Archaic Types, Various:

…”In Nagoya, Yamakichibei, the Hoan and others produced primitive guards, which were later copied or improved upon by their own followers and copyists.”…

One mention under #30 on page 112: T[suba]. Iron, oval, irregular surface, pierced with double gourds and wild boar’s eyes, signed Yamakichi. R.C.Boyle, Esq.

1915: The first decent description and a photograph of Yamakichibei tsuba appears in the colection of Georg Oeder in Düsseldorf [7]. He describes 5 pieces signed Yamakichi and Yamakichibei, №№ 358-362, pp. 42-43.

Fig. 20. Yamakichi (First) tsuba from Oeder Collection

Description translated into English (courtesy my daughter-in-law Renate):

358: TSUBA made of iron, of rhomboid form, perforated with a Hora shell and a cloud-like design. Signed: Yamakichi (First).

359: TSUBA made of iron, of octagonal-round form, with eight perforations in the shape of a wheel . In the style of Yamakichi (First).

360: TSUBA made of iron, with six lobes and six small perforations in different shapes. Signed: Yamakichibei of Owari (Second or Third Master)

361: TSUBA made of iron, of mokkö shape, with file strokes and two opposing perforations in the shape of a butterfly. Signed: Yamakichibei of Owari like №360 (Third Master)

362: TSUBA made of iron, small, with two opposing perforations in the shape of a butterfly. Yamakichi-school.

We see, that by the end of World War I there was at least initial understanding of Yamakichibei tsuba, however, a lot of details remained obscured. Interestingly, Helen C. Gunsaulus in her comprehensive overview of the Japanese sword fittings compiled in 1923, keeps complete silence regarding the matter of Yamakichibei tsuba [11].

1956: In “Japanese swordfurniture collection of the late general J. C. Pabst” [12] on page 29 we see that following mention:

Yama-kichi-work, by Yama-saki Kichi-bei in O-wari and followers, looks like Nobu-ie-work and is often directly copied it. №47: T[suba]. Iron, rough, mokkō-shape, with twelve perforations, like a wheel. Signed: Yama-kichi. [ No photo].

1981: In “Important Japanese Swords” May 5, 1981; Sale 4596Y by Sotheby’s [13] we see №83, without illustration: Losenge-form Yamakichibei style tsuba, 17th century, pierced with two drums, signed Yamakichibei, diameter 7.1 cm.

Let’s now turn to an inexhaustible source of information: Haynes auction catalogues.

November 1981 [32], №39 reads: Good example of Norisuke Yamakichibei tsuba. The well worked and formed plate shows the “wet” surface of this style with many iron bones on the plate and edge. The typical vague signature on the left of the seppa-dai. A classic example. Ht. 7.7 cm, Th. 3.5 mm. Est. price 100-200.

Fig. 20. Norisuke Yamakichibei tsuba.

1982, Catalog #4 [33]: Three examples, № 1058 ($200/300) and dai-sho №№1059A and 1059B ($150/200), again, all three attributed to Iwata Norisuke’s revival school of circa 1850, not to Yamakichibei:

Fig. 21. Iwata Norisuke’s revival school of Yamakichibei tsuba. Ca. 1850.

The same three appears in the next Catalog #5 [34], seems like they did not sell.

One “typical” Norisuke Yamakichibei example in Catalog #6 [35]: With slight amida-yasuri surface and many bold and strong iron bones. The signature with the right arm of the yama kanji cut off is classic to the second Norisuke. Ca. 1850 (#150/300).

Fig. 21. Second Norisuke Yamakichibei tsuba. Ca. 1850

In the same Catalog #6 Rober Haynes provides an expansive description of the Yamasaka Kichibei (of Yamakichibei) school, similar to what is written at “Tsuba. The aesthetic Study”.

Catalog #8 [36] provides three Norisuke Yamakichibei tsuba, including the one already presented in Catalog #6 (Fig. 21):

Fig. 22. Three Iwata Norisuke tsuba signed Yamakichibei. Ca. 1850.

Finally, in Catalog #9 [37] on page 28 we get to four ‘real’ Yamakichibei under the title: Sho-ni-san-yondai Yomakichibei [sic].

Fig. 23. First, Second, Third, and Fourth Yamakichibei tsuba, respectively.

№31: Classic style of the first Yamakichibei. The plate is both well hammered and carved. The sukashi of bird in flight and clouded mountain range [SV: later the design was explained as ‘rusted hatchet’] are typical of this school. The iron bones are restrained and yet powerful. The signature is in the style of the first generation. See Kinko Meikan, page 574, top and bottom right; and Wakayama, vol. II, page 295. In this case the right stroke of the “yama” kanji is not visible, but the enlargement of the nalagoana may account for this. The finest of the Iwata Norisuke Yamakichibei were taken from this style. Ht. 8.5 cm, Th. (center) 3 mm, (edge) 4 mm. $1,000/1,500.

№32: Interesting example of the work of the second Yamakichibei. In this case the plate is thinner than the first and the iron bones in the edge and plate are more pronounced. The design is a slice of fruit. The “yama” kanji can hardly be seen but it does have the stroke on the right side. […] See Kinko Meikan, page 574 bottom photo and Wakayama, Vol. II, page 295 bottom left for this signature. Ht. 8 cm, Th. (center) 3 mm, (edge) 3.5 mm. $750/1,000.

№33: Very fine classic example of the work of the third Yamakichibei. The plate is very heavy and thick, but the amida carving and the surface treatment are very fine. There are only slight iron bones in the edge. The seppadai is signed on the left: Yamakichibei. See Kinko Meikan, page 574 top and bottom left for this signature. Ht. 8 cm, Th. (center) 5.5 mm, (edge) 6 mm. $500/750.

№34: Fine classic example of the work of the fourth Yamakichibei. The plate in this case is average thickness for the period. The rim and edge are very well done with good iron bones. The worm like amidayasuri is also seen in Sendai work of the period. Signed in thin kanji on the left of the seppadai: Yamakichibei. See Wakayama, Vol. II, page 296. Lower right photo for this signature. […] Ht. 8.3 cm, Th. (center) 4 mm, (edge) 4.5 mm. $400/500.

Opposite to the page with four ‘real’ pieces, Haynes places a “Large Yamakichibei style example by second Iwata Norosuke (page 29):

Fig. 24. Yamakichibei tsuba by second Iwata Norosuke, ca. 1850.

№35: The plate is well forged and hammered. The surface is one mass of iron bones on the surface and many on the back. This over-abudance of iron bones was typical of the revival period. The hitsu are not Yamakichibei in style but are Shoami shape. The signature is obscured, as was the case with many of the Norisuke imitations. Never the less this is a very fine piece of forging and shows the great skill of the shinshinto period. Ca. 1850. Ht. 8.5 cm, Th. (center) 3.75 mm, (edge) 4.5 mm. $300/500.

In Catalog #10 [38] on page 20/21we have another “Yamakichibei School” piece, unsigned, and attributed with high probability to Iwata Norisuke (see Fig. 17 for comparison with Second Yamakichibei):

Fig. 25. Unsigned Yamakichibei School tsuba, most probably of Iwata Norisuke, ca. 1850.

1984: First European symposium on the arts of the samurai [18] presented on page 19 under №12 a Yamakichibei (I) tsuba, Momoyama, Pr. Owari from Museum of Decorative Art in Copenhagen.

Fig. 26. Yamakichibei (I) tsuba, Momoyama.

1992: Tsuba from Collection of Dr. Walter Ames Compton (Part I), page 10/11, №5 [15]: A Yamakichibei tsuba. Momoyama period. Signed Yamakichibei. The iron six-lobed plate has a slightly raised edge and many fine iron bones in the rim. The web is hammered and carved with deep grooves which represent the lines which connect the stars of a constellation. These stars are depicted as pierced circles. The hitsu-ana appear to be original but the shape may have been changed – height 6cm., width 5.8cm., thickness at center 3.5mm., at edge 4.25mm. Provenance: Prince Ichijo Sanetaka. Joseph U. Seo, New York. Although most Yamakichibei sword guards in the West are thought to be the work of Iwata Norisuke II, a few are genuine. This example has many features in its favor and can safely be attributed to Yamakichibei I (1575-1615). The inscription on the cover of this box identifies the piece as having once been in the collection of Prince Ichijo. $5,000-10,000.

Fig. 27. First Yamakichibei tsuba. Momoyama period. From collection of Prince Ichijo.

In the Part III of Dr. Walter Ames Compton Collection [15] on page 10/11 under №5 we once again find an Iwata Norisuke II tsuba signed Yamakichibei. Edo period (circa 1850). The iron plate is of four-lobed shape. The surface has Yamakichibei-style hammer work. The plate is pierced with two boar’s eyes, four cloud shapes and a stylized flower. The hitsu-ana is plugged with lead – height 9.3cm., width 8.6cm., thickness 4.5mm. $500-700.

Fig. 28. Iwata Norisuke II tsuba signed Yamakichibei. Edo period (circa 1850).

1992: In the Lundgren Collection [16] on page 67 under №150 (comment in English on page 175): Sword guard with design of sankô (Three Lights: the sun, the moon and the star) in openwork. Signed Yamakichibei. Yamakichi school. Vertical L. 8.00 cm, horizontal L. 7.20 cm, Th. of rim 0.55 cm. Hammer-worked iron. Hair-line engraving and openwork. Early Edo Period, 17th century.

Fig. 29. Yamakichibei tsuba from the Lundgren Collection. Early Edo Period, 17th century.

1993: Henry D. Rosin Collection [14], page36/37, №18: “Yamakichibei. An iron tsuba of mokko shape, pierced in negative openwork with a rusted utensil and a stylized hat, Signed Yamakichibei. Momoyama period. 8.6 x 8.2 x 0.4 cm. Provenance: John Harding. Similar examples: Homma. Masterpieces of Sword Guards, page 71. Wakayama. Toso Kodogu Koza, Volume I, page 35, section 2, page 135. Yamasaka Kichibei was from Owari Province, and was active in the third quarter of the 16th century. The faint vertical lines on this tuba are typical of this artist. They are known as Yamakichi yasuri.” Similar (same) to №31 from Fig. 23.

Fig. 30. Yamakichibei tsuba from Henry D. Rosin Collection, Momoyama period.

1994: On Wednesday 30th of March at Sotheby’s in London [17], pieces from the R. B. Caldwell Collection were auctioned out. Lot №30 was a Yamakichibei tsuba, probably Second generation, Edo period (17th century). Of mokko form, the hammered plate pierced with two double gourds. Signed Yamakichibei, 8.2 cm, GBP 500-600.

Fig. 31. Yamakichibei (II) tsuba from R. B. Caldwell Collection. Edo period (17th century).

The same tsuba is present in Haynes Catalog #6 under №35 with description: “Very fine plate signed Yamakichibei by Iwata Norisuke. The quality of the forging and the iron bones are very powerful. The best work of the second Norisuke, ca. 1850. Ht. 8.2 cm., Th. 2.5 mm ($150/250).” It was sold for fair $70 in 1984 just to appear 10 years later at Sotheby’s and be gone for 517 British Pounds (roughly $775) under the name of Second generation Yamakichibei.

2005: At the 1st Kokusai Tosogu Kai [19], one Yamakichibei tsuba was presented (page 24, J-9, Kazuo Jono Collection:

Fig. 32. Yamakichibei tsuba, Momoyama period (circa end of 16th to beginning of 17th century.

2006: At the 2nd Kokusai Tosogu Kai [20] on page 79, 2-U28, Millard J. Hollbrook II Collection we find another example: “Tsuba, Yamakichibei (3rd Master “Sakura Yamakichi”), Iron plate. Signed: Bishu Yamakichibei with sakura stamp. Zo (elephant) motif. Mid Edo period (Circa 17th century).

Fig. 33. Yamakichibei (3rd Master “Sakura Yamakichi”). Mid Edo period.

And more typical on page 61, 2-U2, Stuart Brooms Collection: Tsuba. Signed: Yamakichibei, Iron plate. Illustrated in Early Japanese Sword Guards by Masayuki Sasano. Avant-garde design (perhaps wood beams) motif. Momoyama period (Circa late 16th century). Lively and skillful work by a great master.

Fig. 34. Yamakichibei tsuba, Momoyama period (Circa late 16th century).

2008: I am lacking the 3rd issue of Kokusai Tosogu Kai, but in the 4th issue [21] on page 50, №4-U1, Timothy Evans Collection, we find another example of Yamakichibei tsuba. “Iron plate. Obscure sukashi motif. Oban form, 89 x 81.5 x 4 mm (Rim) x 3 mm (Center). Circa: Late Momoyama period (16th century).

Fig. 35. Yamakichibei tsuba. Late Momoyama period (16th century).

Here we read:

The sukashi designs are nearly identical to the Shodai Yamakichibei tsuba illustrated in the book by Yasutomo Okamoto, “Owari to Mikawa no Tsubako” on page 176 and are described as ‘inome bori sukashi’. In addition to the heart-shaped (inome) forms, there are other sukashi forms that perhaps depict kushi dango or dumplings on a wood skewer. Most of the signature is intact and does not show as mush of the oblation, scaling or melting that obscures the signatures on many Yamakichibei tsuba.

Yamakichibei tsuba show a strong relationship with raku tea bowls (chawan) and the surfaces were probably produced the same way by repeated firings. Raku bowls express a sense of wabi feeling that was central to the Momoyama period tea ceremony (cha-no-yu), an important aesthetic ritual practiced by Oda Nabunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi as well as their relatives and close retainers. Wabi (literally, powerty) expresses the Buddhist principle of ku, which is described in English as ’emptiness’, or ‘the void’ or ‘formlessness’. The principle of ku was of interest to the Buke as both Miyamoto Musashi and Yagyu Munenori make reference to it in their restective manuscripts ‘Go Rin no Sho’ and ‘Hyoho Kandensho’.

I don’t know if this is a correct understanding of the matter and cite it here as is.

2009: The 5th Kokusai Tosogu Kai [22] on page 44 provides two more specimens – 5-U1 and 5-U2 from Timothy Evans Collection as well.

Fig. 36. Yamakichibei tsuba. 5-U1 |

Fig. 37. Yamakichibei tsuba. 5-U2 |

Fig. 38. Sano Museum exhibition tsuba |

Fig. 36, 5-U1: Signed Yamakichibei. Iron plate. Obscure sukashi motif. Roku-mokko form. 78 x 80 x 5 mm. Circa: Early Edo period (16th century) [SV: this looks like a mistake, as Edo period did not start before the 17th century, 1604]. This tsuba comapers favorably and shows a very strong relationashi to the six-sided mokko wild goose and sickle tsuba illustrated as number 95 in the Sano Museum exhibition catalog, ‘Sukashi Tsuba, Swordgauards with openwork design’, published in 1999 (image here, Fig. 38). These tsuba demonstrate the full canon of Yamakichibei. A tsuba slightly wider than it is high is unusual, and is a characteristic found among Momoyama and Early Edo Period works. Yamakichibei tsuba are thought of as ‘tea taste’ tsuba. This Yamakichibei tsuba expresses the Oribe style of tea, much more so than it does Kikyu or Enshu tea aesthetics. It is noted in several sources that Shodai Yamakichibei worked in Kiyosu, Owari Province. Toyotomi Hidetsugu ruled in Kiyosu from 1590-1595, Fukushima Masanori from 1595-1600, and Tokugawa Tadayoshi 1600-1607. As Fukushima Masanori is identified as one of Oribe’s eight friends, it is likely that this tsuba was made during Fukushima’s tenancy at Kiyosu.

Fig. 37, 5-U2: Signed Yamakichibei. Iron plate. Obscure sukashi motif. Roku-mokko form. 72 x 72.5 x 3 mm. Circa: Early Edo period (16th century). This tsuba is very closely associated to the other Yamakichibei tsuba. The strokes in the inscriptions are very similar, as is the form, proportions and design. You will note the ‘Y’ (it is really an ‘X’ but is partly filled in with scale) shaped mark on the lower left of the larger tsuba. The smaller tsuba has this same mark on the reverse. Similar ‘X’ markings appear on the foot rings of high-level Mino tea wares such as Shino and Kuro-Oribe cha-wan, and Oribe cha-ire.

2010: The 6th Kokusai Tosogu Kai [23] on page 9, 6-J2, Kazuo Jono Collection. Signed: Yamakichibei (2nd generation). Mitsu Mokko-gata, Katabami Sukashi Tsuba. Iron. Circa: Early Edoperiod (17th century). The tsuba is well hammered with good quality iron and design rivaling that of contemporary school such as Owari, Kaneyama, Hoan and Nobuie.

Fig. 39. Yamakichibei (2nd generation) tsuba. Early Edo period (17th century).

2012: The 8th Kokusai Tosogu Kai [24] on page 78, U-RG-01, Richard George Collection. Signed: Yamakichibei. Conch sukashi on Amida (Amidabha) yasuri motif. Iron plate. Circa: Early Edo period (17th century). Dimensions: 69.3 mm (L) x 65.3 mm (W) x 3.8 mm (at the mimi) x 3.3 mm (at the seppa dai). The mokko gata (shape resembling a cut section of Japanese quince) iron tsuba has a uchikaeshi mimi and a surface decorated with fine Amida Yasuri and a conch executed in negative sukashi (opening in the tsuba plate). The piece’s excellent execution and the workmanship are consistent with that sen in early Yamakichibei school pieces.

2014: I have only one more literary source of information, “Iron tsuba. The works of the exhibition ‘Kurogane no hana’ from The Japanese Sword Museum, 2014 [26]. It gives us four examples of Yamakichibei work.

Fig. 41. Yamakichibei, late 16th century. Nata-mon sukashi tsuba (Hatchet design). |

Fig. 42. Yamakichibei, late 16th century. Kama sukashi-tsuba (Sickle). |

Fig. 43. Yamakichibei, late 16th century. Amida-yasuri tsuba. |

Fig. 44. Bishū Yamakichibei (3rd generation), early 17th century. Hachinoki sukashi-tsuba. |

2015: The 11th Kokusai Tosogu Kai [25] on page 24, 11-DM-01, Danny Massey Collection. Unsigned: Yamakichibei (1st generation) [SV: enigmatic statement as the piece is clearly signed; probably a typo]. Korin matsu (korin* pine) motif. {*Ogata Korin (1685-1716}. Tetsu-ji. Circa: Late Muromachi – Momoyama period (late 16th century). Dimensions: 78.0 mm (h), 73.5 mm (w), 3.7 mm (mimi), 3.4 mm (seppa-dai). The so called “Korin-matsu” (Korin pines) are boldly silhouette in this slightly ellipse shaped tsuba. The old namari (lead) is called “Owari ume” (Owari fill) and is precious. Also, the deep black iron emits a sense of age and possesses the atmosphere of an old samurai. The yakite shiage (molten finish), combined with its tsuchimeji (hammered finish) and tekkotsu (rugged finish) are in great harmony with each other. The carving is dynamic but refined with sensitivity. This work represents one of the great tsuba of the first generation Yamakichibei.

Fig. 40. Yamakichibei (1st generation) tsuba. Late Muromachi – Momoyama period (late 16th century).

On page 26, 11-RM-01, Robert Mormile Collection: Signed: Yamakichibei (2nd generation). Kama ni tsuyu (sickle and dewdrop) motif. Tetsu-ji. Circa: Momoyama period (End of 16th to beginning of 17th century). Dimensions: 76.0 mm (h) x 69.0 mm (w) x 2.4 mm (mimi) x 3.1 mm (seppa-dai).

Fig. 64. Yamakichibei, 2nd generation. Momoyama period.

My inability to reach the Okamoto’s Owari To Mikawa no Tanko at the moment makes this publication invalid and handicap. I will update this review as soon as I get hold of the book.

Now, what we have online.

Fig. 45. Yamakichibei. Early Edo.

Fig. 45: Tetsugendo.com. Yamakichibei was a famous Owari province smith that was famed for his iron tsuba. He created works that had bold and daring iron (tetsuji) coupled with rustic designs that became highly sought after for their uniqueness. The iron has a beautiful deep luster and amida yasuri. The tekkotsu is rugged and strong. Large sukashi cutout design is of dragonfly.

NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon papers. Early Edo. Signed – Yamakichibei. Size: 7.1 x 6.85 x 0.34 cm.

Fig. 46. Late imitation of Yamakichibei tsuba, possibly mass-produced at the end of Edo period.

Fig. 46: gomabashi.blogspot.com. Here is a rather interesting piece – an iron tsuba with kawari-gata hitsu-ana (irregular shape of the kozuka and kogai holes). The plate finished with hammering (tsuchime-ji) slightly raised rim and a very faint, yet skillfully done Amidayasurime (filemarks or carving representing the halo emanating from Amida Buddha). The plate is dark-brown, with purple reflections, with speckles of red rust. Granular and linear iron bones (tekkotsu) along the edge. Dimensions: 8.5 x 7.9 cm; Seppa-dai thickness: 3 mm; Rim thickness: 4 mm.

Fig 47 a-b-c-d.

Fig 47, a-b-c-d (also from gomabashi.blogspot.com): “This tsuba is not papered, however, so my belief that it is an early-Edo Yamakichibei is based on a lot of study of the Yamakichibei artists. The metal in this guard—its forging and its tsuchime—the subtle yakite-shitate, the type of mokko-gata, and the mei all suggest to me a Yamakichibei of the early 17th century. (In) the book Owari to Mikawa no Tanko, by Okamoto, I believe you can find a photo of a Yamakichibei tsuba with a very similar treatment of the sukashi/hitsuana elements”. Few pictures of real Yamakichibei tsuba, courtesy of Steve Waszak. Posted 27th February 2010 by Goma Hashi.

Jim Gilbert provides two examples:

Fig. 48. Yamakichibei 1st, ca. Momoyama.

Fig. 48: Yamakichibei Tsuba, ca. Momoyama. 7.1 cm H x 7.0 cm W x 0.2-0.4 cm T. Iron with tekkotsu in the mimi and face. Muttsu Mokko gata (six-lobed shape) Kaku mimi ko-niku. The sukashi pattern at the top is a hat and the bottom is a modified udenukiana. There is a slight trace of the yama in the signature remaining to the left of the nakago ana. It has been partly removed in the installation of the copper insert. The surface is varied and rich with a rustic flavor. Unusual Sasano origami to shodai [SV: 1st generation] Yamakichibei.

Fig. 49. Yamakichibei 2nd, ca. early Edo.

Fig. 49: Signed Yamakichibei, ca. early Edo. 8.07 cm H x 7.33 cm W x 0.53 cm T at the mimi. Iron with tekkotsu in the mimi and face. Mokkogata. Kakumimi ko-niku. The signature and workmanship are typical of the second generation. The tekkotsu on the rim are extremely pronounced, appearing as many small diameter but high relief bumps. The meaning of the sukashi motif is not at all clear. NBTHK Hozon origami to nidai [SV: 2nd generation] Yamakichibei.

John Stuart Yamakichibei:

Fig. 50. Later copy of a Yamakichibei tsuba

Fig. 50: A later copy of a Yamakichibei tsuba showing tekkotsu with a good steel plate, having a yakite shitate 焼手仕立 a re-fired and slightly melted surface.

Andrew Quirt gives us one example:

Fig. 51. Iwata Norisuke or Yamakichbei 1st tsuba.

A large moku tsuba signed Yamakichibei. Good color and globular tekotsu on the face and the rim. Lead sekigane in the kozuka ana, and copper in the center opening. I am reasonably sure that this Iwata Norisuke, Haynes felt that it was possibly the first generation. 8.67 cm x 7.98 cm x 3.2 mm. $500. [SV: Author’s syntax retained].

Grey Doffin has quite a few Yamakichibei tsuba on his website (most of the already sold):

Fig. 52. Yamakichibei School. |

Fig. 53. Kodai Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 54. Yamakichibei 2nd. |

Fig. 55. Signed Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 56. Kodai Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 57. Signed Yamakichibei |

Fig. 58. Yamakichibei 3rd. |

Fig. 59. Yamakichibei 3rd. |

Fig. 60. Signed Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 61. Signed Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 62. Signed Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 63. Signed Yamakichibei. |

Fig. 62. Signed Yamakichibei. Shinsa (inspection board) confirmed it’s a gimei (false/counterfeit signature).

Here I just combine the images kindly provided by various collectors via Nihonto Message Board:

Fig. 65. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba |

Fig. 66. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba |

Fig. 67. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba |

Fig. 68. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba |

Fig. 69. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba |

Fig. 70. Meijin Shodai (1st generation) Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 71. Meijin Shodai (1st generation) Yamakichibei tsuba.

|

Fig. 72. Meijin Shodai (1st generation) Yamakichibei tsuba.

|

Fig. 73. Early Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 74. Yamakichibei tsuba.

Momoyama to early-Edo period

|

Fig. 75. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 76. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. 8.4 x 8.3cm. |

Fig. 65 to Fig. 73 – courtesy Steve Waszak, with his attribution.

Fig. 74 – courtesy Barry Thomas. Iron, wakizashi-sized at 69 x 63mm, 2.5mm at the nakago-ana, 3mm at the mimi. The iron displays the classic Yamakichibei yakite treatment, complementing the tekkotsu and tsuchime that also characterize Yamakichibei guards. The sukashi design has been described as a partial wheel or as an allusion to a fist (the sukashi openings being roughly where one’s knuckles would be when making a fist). Momoyama to early-Edo period.

Fig. 75 and 76 – courtesy Evan Worley.

One more piece from Steve Waszak:

Fig. 77. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba.

Now, photos from Okamoto’s Owari To Mikawa no Tanko:

Fig. 78. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 79. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 80. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 81. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 82. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

Fig. 83. Nidai Yamakichibei tsuba. |

To complete this incomplete compilation, I would like to cite the comment that accompanies Robert Mormile tsuba in 11th Kokusai Tosogu Kai (page 26, 11-RM-01, see above):

“Here we have an example of mokko-gata iron tsuba made for shoto or wakizashi. The work is believed to be that of Yamakichibei. The tsuba features sukashi of an agricultural and satoyama woodland tool known as kama. We can observe the placement of flanked dewdrops that offer a visual counterpoint and accentuate the teeth of the kama. The viewer will also note that the artistic decision was made to have the outer edge of the hitsuana follow the outline drawn by the mimi completing the balanced composition. There is pronounced Amida-yasuri throughout the ji, the deepest of which, found carried through on the outer side of the kama sukashi. The rustic sobriety and unpretentiousness of the ji-gane achieved by the Yamakichi lineage is perfectly in keeping with Zen aesthetic sensibilities that were popular during its time of manufacture.

The reasoning behind the nidai attribution being in part the first stroke of the yama character is in the form of a dot complimented with a separated curved second stroke that the nidai was known for. (As we know, the nidai and sandai applied their signatures before the final hardening as was the case for this example). Furthermore, the overall quality, purple-ish color and abudance of globular and linear tekkotsu, the presence of sukinokoshi-mimi as well as uchikaeshi-mimi illustrates the close relationship to the origin of the school. Unfortunately, when the tsuba was remounted (note the secondary sekigane) parts of the signature were lost due to widening the seppa-dai to snuggly secure the new mounting.

As one of the fundamental principles of Zen Buddhism is the idea of denying the ‘self’ and the admonishment of desire, the philosophy was encouraged by daimyo and adopted by the samurai from the Kamakura Period forward. Japanese artists have long used artistic interpretations of vehicles or instruments such as ox carts, wheels, boats, rudders, sickles, staffs, and the like, to communicate this principle of life being a ‘tool’ to achieve Buddhist enlightenment as is the case with the example here. These graphic representations serve as a constant reminder of the idea of accepting the reality of death at a moment’s notice. The kama is a tool to make-clear the field and satoyama woodland (an important source of fuel, food, compost, etc.) that is life, and, living by the sword is making-clear the current and future path of the swordsman.”

After writing this review, I got interested in Yamakichibei workshop production. I then had a chance to meet and befriend a few people who are collecting and studying Yamakichibei tsuba, first of all professor Steve Waszak of San Diego. With his kind help I managed to acquire two Yamakichibei Nidai pieces and, recently, one first generation Yamakichibei tsuba.

Yamakichibei Nidai TSU-0393.2019

As an important update to the scholarship of Yamakichibei tsuba, I gladly cite a paper by Steve Waszak, published in three consequent issues of Japanese Sword Society of the United States: JSSUS Newsletter, Volume 50 NO. 5, Sept. – Oct., 2018; Volume 50 NO. 6, Nov. – Dec., 2018; Volume 51, NO. 1, Jan. – Feb., 2019.

Selected references:

1] Tsuba. An aesthetic study. By Kazutaro Torigoye and Robert E. Haynes from the Tsuba Geijutsu-kō of Kazataro Torigoye. Edited and published by Alan L. Harvie for the Nothern California Japanese Sword Club, 1994-1997.

2] Tsuba Geijutsu-Ko by Kazutaro Torigoye, 1960.

3] Tsuba no Bi. Written by Susumu Kashima, Eiroku Hayashi and Hirokichi Matsunaga, 1947.

4] Markus Sesko. Encyclopedia of Japanese swords, 2014.

5] Kodogu and tsuba. International collections not published in my books. (Toso Soran). Ph. D. Kazutaro Torogoye. 1978.

6] Japanese sword guards. Some tsuba in the collection of Sir Arthur H. Church. Privately printed, 1914

7] Japanische Stichblätter und Schwertzieraten. Sammlung Georg Oeder Düsseldorf. Beschreibendes Verzeichnis von P. Vautier. Herausgegeben von Otto Kümmel. Oesterheld & Co / Verlag / Berlin, Oesterheld, 1915.

10] Henri L. Joly and Kumasaku Tomita. Japanese art and handicraft. An illustrated record of the loan exhibition held in aid of the British Red Cross in October – November, 1915. London, Yamanaka & Co, 1916.

11] Japanese sword-mounts in the collection of Field Museum by Helen C. Gunsaulus, Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology. 61 plates. Berthold Laufer, Curator of Anthropology. Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 216, Anthropological Series, Volume XVI; Chicago, 1923.

12] Japanese swordfurniture collection of the late general J. C. Pabst which will be sold by auction by Van Stockum’s Antiquariaat (J. Kuipers) at the galleries Prinsegracht 15,The hague, on Tuesday, the June 26th, 1956. Photos and cliché’s: Biegelaar & Jansen – Utrecht. Printing: G. M. Van Gent – Ridderkerk.

13] Important Japanese Swords, Fittings, and Armour, Including the Collection of Alfred J. Cohn, Richmond, Virginia, and a series of important blades and fittings including An Highly Important Dated Tachi by Shodai Tadayoshi, An Extremely Rare Daito by Founder of the Bungo School, Bungo Sadahide (Jōshu). Catalogue for May 5, 1981; Sale 4596Y). // Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc.

14] The Henry D. Rosin Collection of Japanese Sword Fittings. An exhibition held at Syz Limited, London from 11th to 25th June 1993; Catalogue by Patrick Syz.// Published by Syz Limited, London, 1993.

15] Japanese Swords and Sword Fittings from the Collection of Dr. Walter Ames Compton (Part I, II & III). Specialists in charge: Sebastian Izzard and Yoshinori Munemura. Christie’s, New York, March 31, 1992.

16] Japanese sword-fittings and metalwork in the Lundgren Collection. Published by Otsuka Kogeisha Co., Ltd., Tokyo 1992. Produced by Kamakurayama Kikaku.

17] Japanese Sword Fittings from the R. B. Caldwell Collection. Sale LN4188 “HIGO”. Sotheby’s, 30th March 1994.

18] First European symposium on the arts of the samurai, German sword museum, Solingen. Hamburg, Copenhagen, Geneve, Paris, London. 100 selected tsuba from European collections. Catalogue by Robert Haynes and Robert Burawoy. 1984.

19] Kokusai Tosogu Kai, International Convention & Exhibition, September 24-25, 2005, The Frazier Historical Arms Museum, Louisville, Kentucky, USA.

20] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; The 2nd International Convention & Exhibition, October 18-23, 2006 at Takashimaya Department Store, Nihonbashi, Tokyo, Japan. [KTK #2]

21] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 4th International Convention & Exhibition, October 17-20, 2008 at Intercontinental Hotel in Toronto, Canada.

22] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 5th International Convention & Exhibition, October 28-30, 2009 at NEZU Museum, Tokyo, Japan. Collaboration with the Nihonto Bunka Kyokai General Foundation.

23] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 6th International Convention & Exhibition, October 6-8, 2010 at Cooperation with Vancouver Museum.

24] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 8th International Convention & Exhibition. In conjunction with the “Samurai” Exhibit at the Fraizer History Museum, May 11th and May 12th, 2012.

25] Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 11th International Convention & Exhibition. Chicago, Illinois, USA. April 22 & 23, 2015.

26] Iron tsuba. The works of the exhibition “Kurogane no hana”, The Japanese Sword Museum, 2014.

27] Shinkichi Hara. Die Meister der japanischen Schwertzierathen. Ueberblick ihrer Geschichte, Verzeichniss der Meister mit Daten ueber ihr Leben und mit ihren Namen in Urschrift. Hamburg, 1902.

28] Okabe-Kakuya. JAPANESE SWORD GUARDS. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In cooperation with the department of Chinese and Japanese art; – 1908.

29] Bulletin de la Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris, juin-septembre 1910, №19-20 plus un volume intitulé Planches pour accompagner l’article de M. Charles Leroux sur la musique japonaise. Incl.: Comte de Tressan: L’évolution de la garde de sabre japonaise de la fin du XVe siècle au commencement du XVIIe (suite), 34 illustr.

30] Tsuba Kanshoki. Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975.

31] Japanische Schwertzieraten. Text. Gustav Jacoby. Verlag von Karl W. Hiersemann, Leipzig, 1904.

32] Highly important Japanese swords and kodogu. San Francisco, November 13-15, 1981. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

33] Important Japanese tsuba, early iron and kindo examples. San Francisco, November 1-28, 1982. Catalog #4. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

34] Fine Japanese tsuba, fittings, woodblock prints, netsuke, inro and books on swords and tsuba. San Francisco, March 1-27, 1983. Catalog #5. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

35] Important tsuba, menuki, bokuto, woodblock prints, koshirae, sword pistol and kana mono. San Francisco, June 1-26, 1983. Catalog #6. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

36] Important signed Shoami tsuba. Collection of menuki, kozuka, and fuchi-kashira. Interesting and important 19th and 20th century woodblock prints and books. San Francisco, January 16 – February 12, 1984. Catalog #8. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

37] Masterpiece and highly important tsuba, menuki, and fuchi-kashira from eminent collections in America, England, France, and Japan. San Francisco, May 8-12 and May 21-27, 1984. Catalog #9. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

38] Important tsuba, menuki, kozuka, fuchi-kashira, kabuto, reference books and woodblock prints. San Francisco, September 10 – October 14, 1984. Catalog #10. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.