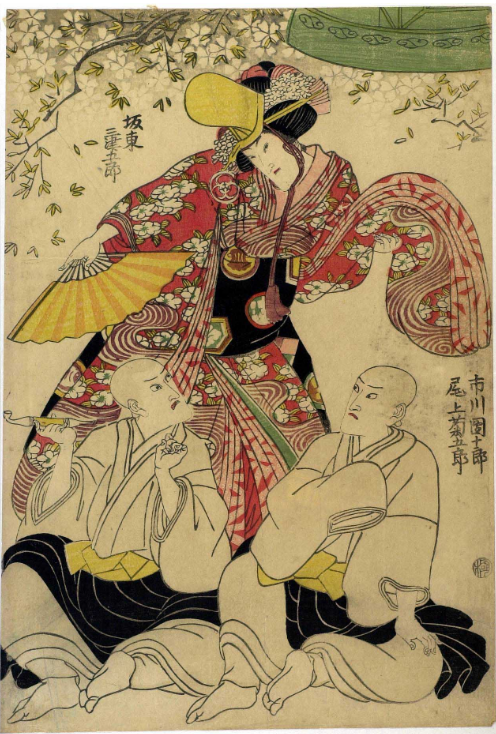

In October 2014 I purchased on eBay a stack of Toyokuni I prints at a very modest price. While most of these new prints I easily identified with the help of ukiyo-e.org, one design had no matching images anywhere on the Internet:

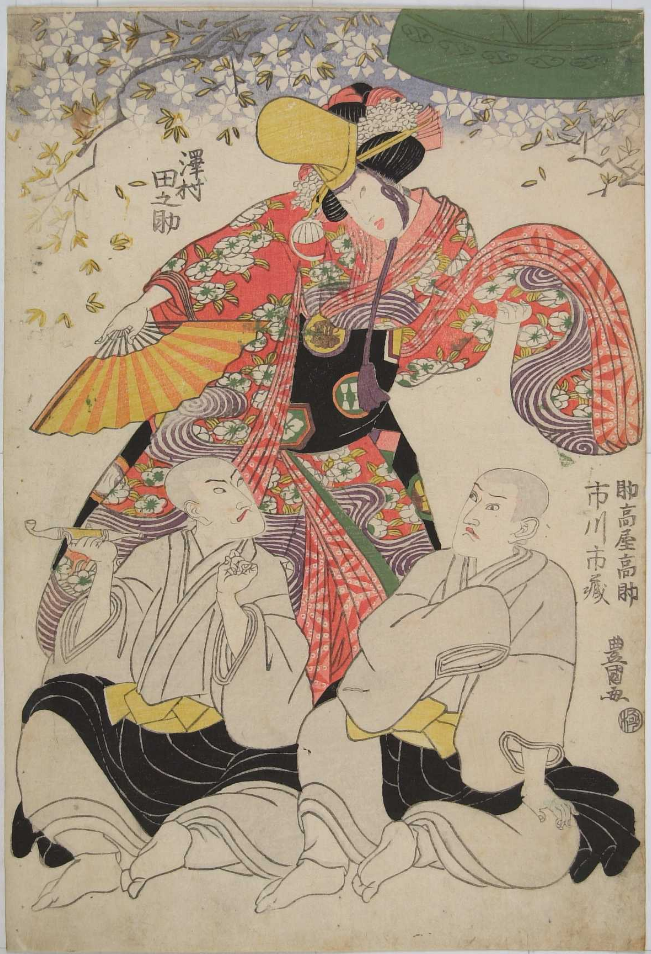

Seller, a reputable London-based ukiyo-e dealer, identified the actors as the kabuki actors Bando Mitsugoro, Ichikawa Danjuro and Onoe Kikugoro. The year was marked as ‘circa 1815’, with no play title or theater mentioned in the item description. As I stated before, ukio-e.org search did not return an image similar to my print, however, it provided five images that looked very much like:

Bando Mitsugoro, Ichikawa Danjuro, Onoe Kikugoro. Nakamura Theater; 1816. Risumeikan University |

Tanosuke Sawamura, Sukedakaya Kosuke, Ichizo Ichikawa. Nakamura Theater; 1813. Waseda # 201-5342 |

Utaemon Nakamura, Sukedakaya Kosuke, Ichizo Ichikawa. Nakamura Theater; 1812. Waseda # 001-1211 |

Tanosuke Sawamura, Sukedakaya Kosuke, Koshiro Matsumoto. Ichimura Theater; 1810. Waseda # 001-1211 |

Tanosuke Sawamura, Sukedakaya Kosuke, Koshiro Matsumoto. |

The first print in this sequence represents three artists, namely Bando Mitsugoro, Ichikawa Danjuro, Onoe Kikugoro (same as on my print), who played in a year Bunka 13 (1816) at Nakamura Theater in Edo. The play is a variation of dance performance based on Dōjōji (or Dōjō Temple) legend. No artist name, no publisher’s mark is present. Comment from Risumeikan University conveys detailed description of what likely to have happened to this design:

“Represented is the ceremonial folding fan dance at Dojoji. In this picture, on the occasion of this performance, the faces of the actors and their names were re-carved, and was again reprinted. The current picture is the third edition. The first edition dates to Bunka, 7th year (1811), the second edition – to Bunka 9th year (1813). In the current edition shows traces of revised carving around the faces of the three men (the horizontal lower line of the faces of Danjūrō and Kikugorō, and the diagonal line at the lower left line of the face of Mitsugorō were easy to change). Here the ink woodblock (the key block) for the face’s boundary part is cut out squarely (in a square fashion), is filled in by a new block and is replaced by the face of another actor. As to the color blocks, no changes are visible after the second publication; perhaps was remade anew; In this image, the sakura flower petals in the upper part of the picture surface and on the design on the costume of the three men, etc., have become considerably different. In this print / edition, the originally present seal of the publisher is absent / is deleted. Perhaps, the publishing house Hirano Chozaemon (平野長右衛門) that printed prints up to the second edition, sold out the woodblocks, and this one is perhaps a publication of the different publisher that purchased . On top of this, because the signature “Toyokuni ga” was also eliminated, representation of the replaced faces was possibly by the artist other than Toyokuni I.” [Translation generously provided by my sister].

Actor prints in XIX century Japan were a commodity, catering to the desires and tastes of the urban masses. These prints served the same function as now served by the photographs of Hollywood celebrities. When blocks were carved, they became the property of the publisher, who could print them in any variation of colour, re-sell, re-print, re-carve, and alter in any way. I assume that my print was produced by Toyokuni I and published by Mikawaua Seiemon in 1816 partly in response to uncontrolled reproduction of the re-carved 1810 design.

Both Risumeikan and Waseda scholars associate their respective prints with the dance drama “The Maiden at Dōjō Temple” (Kyō-ganoko musume dōjōji), though it could have gone under various stage titles. The kabuki drama was first staged in the 3rd lunar month of 1753 in Edo at the Nakamura Theater. The main role of the dance was played by the great star Nakamura Tomijûrô I. The performance’s success was beyond expectation and it was extended for several months. The kabuki performance has borrowed its substance from an earlier Noh play “Dōjō Temple” (Dōjōji), performed during the sixteenth century by Kanze school.

The legend of Dōjō Temple is possibly the best-known tale in Japan. It stems from pre-modern Japanese literature, anthologies of buddhist myths and legends (setsuwa):

- Dai-Nihon Hokekyō Genki (Hokke Genki), c. 1040-44.

- Konjaku Monogatari, c. 1120.

- Genkō Shakusho, 1332.

The 14th century Dojoji Engi Emaki (The Illustrated Legend of Dōjōji) is the first expression of the Dōjōji legend in illustrated narrative scroll form. “The requirements of the setsuwa genre allow relatively little interpretive play to setsuwa versions of the Dojoji legend, for the audience is bound to the hermeneutic expressed overtly in the text and covertly through the generic context of the Buddhist tale collection. The tale functions as a relatively conventional, if lurid, account of a lustful woman turned serpent and of the power of homage to the Lotus Sutra. Recast into the format of an illustrated scroll (emaki), however, the Dōjōji legend emerges as an independent work in its own right, with a new dynamism and fascinating ambivalence.”[1].

“Although all etoki narratives convey Buddhist morals and doctrines, many of the do not appear to treat Buddhist subjects, at least not immediately. The story is better known by its folklore title Anchin and Kiyohime; Kiyohime represents a woman possessed by unrequited love for ascetic monk Anchin. The picture scroll graphically illustrates how the enraged woman transforms herself into a grisly serpent and chases the ascetic to Dōjōji where monastics hide him inside temple bell. The she-serpent wraps herself around the bell and scorches the entrapped ascetic with her wrathful fire. The story, while engrossing, seems to have nothing to do with Buddhist doctrines. Yet when this animated story is performed in the context of Buddhist etoki, the woman’s action is explained as a demonstration of earthly desire that keeps her from reaching nirvana. …The oldest existent scroll set at Dōjōji (dated before 1573) may have been copied after the lost fourteenth-century original”[2].

In the pre-modern versions of the Dōjōji tale, the woman and the monk are nameless. According to Dōjōji Engi Emaki, the events took place ‘long time ago’, in the year 928, at the village of Manago, the banks of Hidaka River, and the Dōjō Temple. At the end, when both the ascetic and the she-serpent were dead, the old monk of Dōjōji transcribed the Lotus Sutra and dedicated it on behalf of the dead. As a result, they were reborn in the heaven. “All may rely on the intercession offered by the Lotus Sutra. It should be ceaselessly. Immediately abandon provisional means and teach only the highest path”.

The Noh play survived until today, probably in its original form[3]. Who wrote it is unknown, however, tradition attributes it to the creators of Noh theater Kan’ami Kiyotsugu (1333 – 1384) and his son Zeami Motokiyo (c. 1363 – c. 1443), or to Zeami’s grandson Kanze Kojiro Nobumitsu (1435 or 1450 – 1516?). By Zeami’s classification of female Noh plays it belongs to the fourth category – the crazed-women plays, or Madness Noh (monogurui no), in which the main character grieves over a forced parting with a loved one[4]. In other sources Dōjōji is classified as exorcism piece (inori mono), resentful attachment piece (shûnen mono), and as devoted attachment piece (shûshin mono) – depending on the other plays in the program[5]. The plot substantially differs from the original setsuwa and engi versions. Time is ‘our days’ and the only place of action is the temple of Dōjō, and it is clearly identified as ‘a fourth-category play of attachment’. Buddhism treats ‘attachment’ as one of the major obstacles in attaining nirvana. After centuries that passed since 928, the Dōjō Temple finally receiving a new bell to replace the one destructed by the she-serpent in her pursuit of the monk. As a measure of precaution, women are banned from the Temple grounds. However, the monks allow a young and beautiful female dancer (shirabyōshi) to enter the Temple precincts and perform her dances at the dedication of the new bell. “A the climax of her dance, the dancer knocks off her tall cap and stands under the large bell prop with her hands raised. As the bell falls, she leaps under the bell and transforms to an ugly demon, a serpent, revealing her real nature”. [Karen Brazell].

Through 18th and 19th centuries, the Noh version of the legend was also presented in various forms on the kabuki stages. “In transformation from Noh to kabuki, the well-structured content turned into a series of dances with a clear dramatic development. It was produced for the first time in 1723. It was modified several times until 1753, when the successful and long performance of The Maiden at Dōjō Temple at the Nakamura Theater in Edo, produced by famous onnagata Nakamura Tomijûrô I, became the standard version”[6]. The play has the following characters: Hanako – a shirabyōshi dancer, but in reality, the ghost of Kiyohime; Odate Gorō – demon-queller (also called Ōdate Sadogorō); Priest 1; Priest 2; the other priests. The dance of Hanako constitutes the center piece of the play. It consists of 9 consequent dances: (1) travel dance (michiyuki) in black kimono with cherry decorations and golden fan; (2) shirabyōshi dance in red kimono with a gold eboshi cap; (3) energetic iwazu katarazu dance with a silver tiara on dancer’s wig; (4) mari uta dance representing pleasure quarters in different parts of Japan, in pale blue kimono, miming the shaping of a ball of cherry blossoms; (5) kasa odori dance in light blue underkimono with a string of red flat hats; (6) the lamentation dance (kudoki) in lavender coloured kimono with a white silk towel (tenugui); (7) yama zukushi dance dedicated to various Japanese sacred mountains with a little drum (taiko) attached to her waist, in a yellow kimono with a drum pattern; (8) te odori dance in red or purple underkimono, dancer beckons a lover and waves her hands happily; (9) suzu daiko dance with tambourines. At the end of the dance Hanako circles the bell in a white kimono and at last poses on top of the bell: “The dancer mounts the bell and poses dramatically on top of it as the curtain is pulled shut” [Karen Brazell].

At the scene captured by the artist Hanako performs the second dance (shirabyōshi). The fox-like pose of the Priest 2 alludes to Inari – the Shinto shrine of Inari, the spirit of rice and sake, the worldly pleasures. In yama zukushi dance (#7) “Hanako… is making foxlike gestures with her hands at mention of the fox shrine of Inari” [Karen Brazell]. The other priest with a pipe conveys the same notion of worldly pleasure: smoking. Again, the Noh and Kabuki adaptations of the tale have departed from the original setsuwa/engi version chiefly by switch in time of action from ‘then’ to ‘now’, and by introduction of the Priests 1 & 2. While the former contemporises the play, makes it look and feel modern, the priests are used to demonstrate the expanded the power of lust and attachment. Instead of being austere, these two ‘ascetics’ are explicitly interested in eating flesh, drinking spirits, and smoking. Lustfulness of the priests is the main reason why a young and beautiful shirabyōshi dancer was permitted to enter the Dōjō Temple premises, despite of a strict centuries-long ban. Another important deviation from the original legend, is complete disappearance of any mention of Lotus Sutra. However, the legend is so old and so well known to any potential receiver, that even the slightest hint of presence of Dōjōji bell on stage or print thunderously rings for the Japanese ear the sound of Buddhist moral.

Symbols on the black obi of the shirabyōshi dancer are the family crests of the past warlords and rulers of Japan, while the circle with three red inscribed triangles may also represent the snake’s scales, the serpentine nature of Kiyohime (in the Noh version “the dancer traces triangles on the stage, matching the serpentine triangles in her costume…” [Karen Brazell]. The crests on my print are: mokko-shaped flower in hexagon (kikko)— represent the Naoe clan, triangles (uroko) in a circle — the Hōjō clan, three stripes (sangi) in a circle — the Miki clan[7]. On other variations of the same scene by Toyokuni I and other artists before and after him we see other family crests, e.g. with pestles, with two vertical stripes, cotton, crane, etc., but the triangles are always present.

Now, I think, I can relatively confidently suggest that my print depicts the shirabyōshi dancer Hanako (Bando Mitsugoro III ), and the Priests 1 (Ichikawa Danjuro VII on the right holding a pipe) and Priest 2 (Onoe Kikugoro III on the left, miming a fox) in kabuki play “The Maiden at Dōjō Temple” (Kyô-ganoko musume dôjôji). I would also assume that my print, similarly to Risumeikan’s print, relates to the play staged at Nakamura Theater in a year Bunka 13 (or 1816).

The masters of ukiyo-e turned to the theme of “The Maiden at Dōjō Temple” quite often. The 18th century prints include:

Actor Segawa Kikunojô I in Momo Chidori Musume Dôjô-ji. 1744. Torii Kiyomasu II, Publisher Nakajimaya Izaemon. Play: Momo Chidori Musume Dôjô-ji. Theater: Nakamura. MFA impressions: 06.423, 21.5457. |

Katsukawa Shunshō, c. 1772. The actor Arashi Hinaji I in “Musume Dōjōji”[8]. |

Katsukawa Shonshō. The actor Arashi Hinasuke I as Watanabe Chōshichi Tonau in Tokimekuya O-Edo no Hatsuyuki. Morita Theater, 1780.[8] |

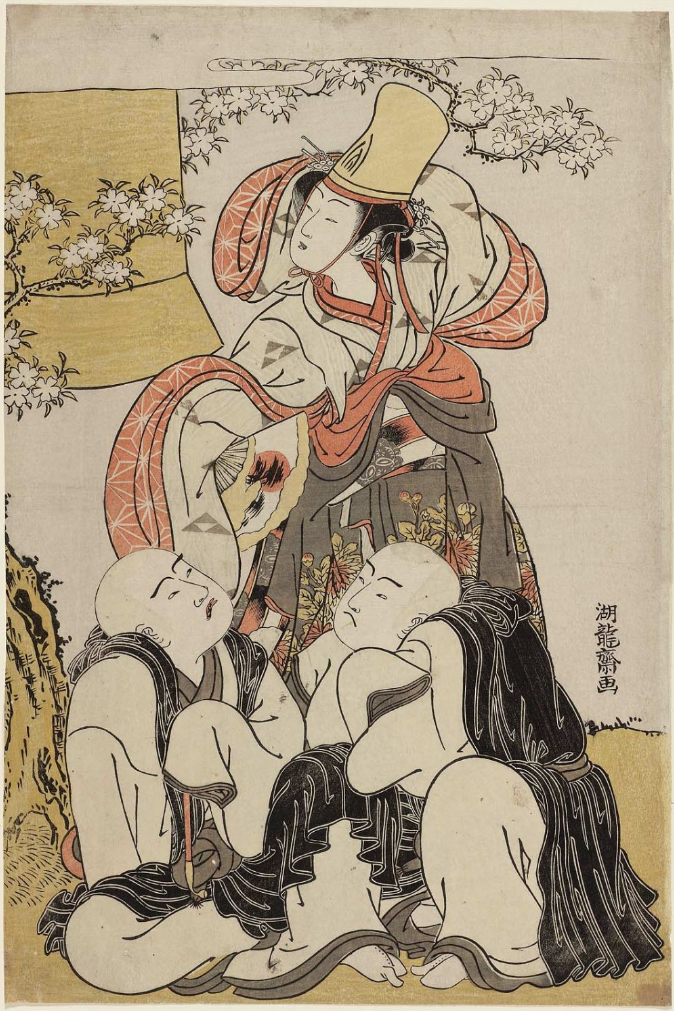

Isoda Koryûsai. Dancer and Two Priests, from the Play Dôjô-ji, c. 1772–81. MFA # 11.21799. |

In the early 19th century Toyokuni I also produced a surimono “Private Performance of Women’s Kabuki: Dôjô-ji” and an ōban print with the string of hats scene:

Private Performance of Women’s Kabuki: Dôjô-ji. Utagawa Toyokuni I; Publisher Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudô). MFA |

Actor Yoshizawa Enjirô I as a Shirabyôshi Dancer, with Matsumoto Kôshirô V and Sawamura Gennosuke I as Priests. Utagawa Toyokuni I, Publisher Shimizu. Play: Kyôganoko Musume Dôjô-ji. Theater: Ichimura. MFA # 11.41484; BM # 1906,1220,0.416 |

- Virginia Skord Waters

. Sex, Lies, and the Illustrated Scroll: The Dojoji Engi Emaki

. // Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Spring, 1997), pp. 59-84.↩ - Ikumi Kaminishi. Explaining pictures: Buddhist propaganda and etoki storytelling in Japan. // University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2006.↩

- Конрад Н.И. Избранные труды. [Том 3]. Литература и театр. — М.: Наука, 1978; c. 359—384, Японский театр (Но, Дзёрури, Кабуки).↩

- Minae Yamamoto Savas. Feminine madness in the Japanese Noh theatre. // Dissertation, The Ohio State University, 2008.↩

- Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays (Translations from the Asian Classics) edited by Karen Brazell.// Columbia University Press, 1998.↩

- Arendie and Henk Herwig. Heroes of the Kabuki Stage: An Introduction to the World of Kabuki With Retellings of Famous Plays Illustrated by Woodblock Prints. //Hotei Publishing, Amsterdam, 2004. p.211-215↩

- John W. Dower. The elements of Japanese design. A handbook of family crests, heraldry & symbolism. Weatherhill, Inc., 1985.↩

- The actor’s image. Print makers of Katsukawa school. The art institute of Chicago and Princeton University Press, 1994. p.183 and 261.↩

Other sources:

Susan B. Klein. Woman as Serpent: The Demonic Feminine in the Noh Play Dojoji.