«Naturally they [the “experts”] have not seen enough tsuba to fully evaluate the true age of many tsuba they have no knowledge of.»

Robert D. Haynes[31]

Motivation behind this work

Though the name “Ōnin tsuba” appeared in the Western literature in the beginning of the 20th century, there was no terminological uniformity until today. The names used were: Ōnin, Ōnin School, Ōnin Style, Ōnin-fu tsuba and even Heianjō cum Ōnin. I was confused: Do we use different words to describe the same thing? What about such terms as ‘early brass inlay’, fushimi-yoshiro zōgan, heianjō tsuba, etc.? What is ‘early’? For the sake of clarity, I decided to spend some time and research the issue.

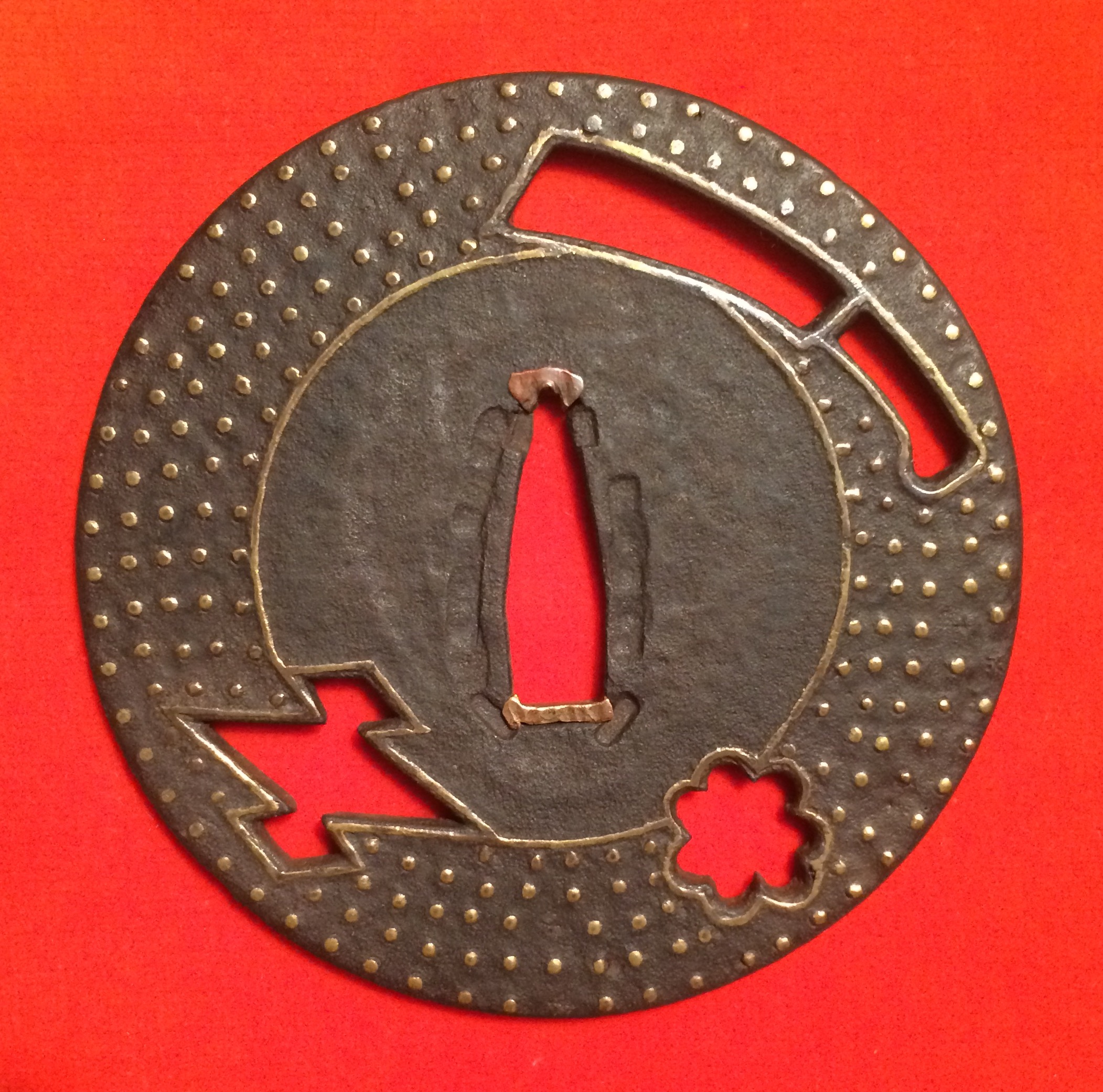

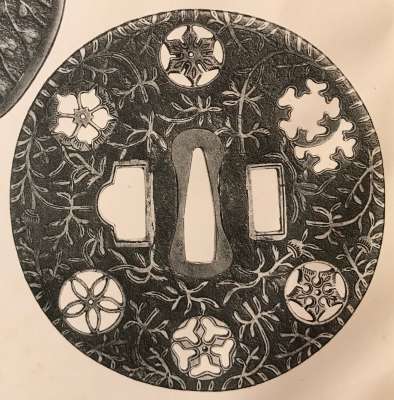

Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba with a Snowflake, a Triple Diamond, and the Ockham’s Razor in openwork. Late Muromachi period.

First half of the 20th century

In 1910 Henri L. Joly published a book (though the print was limited to 300 copies) with thorough description of the collection of J. C. Hawkshaw, Esq.[3]

Chapter “The Yoshiro and Fushimi Styles of Inlay” says:

“The work generally called Fushimi derives its name from the town of Fushimi in Yamashiro where in 1587 Hideyoshi built a castle. It is often stated that the style of brass inlay on iron characteristic of that school originated in the Fifteenth Century in the Ōnin period (1467-1469), hence the name of Ōnin tsuba given to thin iron guards inlaid in an archaic manner with somewhat crude designs of crests and natural objects. The other name, Yoshiro zōgan, is derived from that of an inlayer: Koike Naomasa Izumi no Kami, also called Koike Yoshiro. There is an almost arbitrary distinction whereby the thin tsuba with almost flush brass inlay now called Ōnin tsuba were called Fushimi inlay together with a great deal of flat hirazōgan work, and the name Yoshiro was reserved to those presenting high inlay of large design in brass, and to the “Mon zukashi” type, with open-work crests inlaid in brass sometimes with addition of silver wire which originated either with Koike Yoshiro or with Nagayoshi. The signature Koike Yoshiro is rather rare, sometimes the names Saburo Daiyu and merely Yoshiro are also found. […] Much of so-called Yoshiro work was done in Kaga; it is more refined, and the use of copper, silver, and later Shakudo together with the brass inlay gave early Kaga work a peculiar appearance.”[3]

We have to admit that Joly’s statement regarding “Ōnin tsuba” is as confusing as possible. On the one hand, it’s just a new name of “the thin tsuba with almost flush brass inlay”. On the other hand, there is some sort of “Fushimi inlay tsuba” with “a great deal of flat hirazōgan work”. What’s the difference between “Fushimi inlay, flash inlay” and “hirazōgan work”? Joly states that the difference between Ōnin tsuba and Yoshiro tsuba is “almost arbitrary”, but describes Yoshiro tsuba as “those presenting high inlay of large design in brass, and to the Mon zukashi type, with open-work crests inlaid in brass” and Ōnin tsuba as “thin iron guards inlaid in an archaic manner with somewhat crude designs of crests and natural objects”. This two things doesn’t sound similar at all. Then, Joly calls all of these tsuba “Fushimi-Yoshiro”, and illustrates his perception with the following examples:

#31. Plate XXV. Kaga and Zogan. |

#42. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 16th-17th century. #42. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 16th-17th century. |

#45. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 16th century. #45. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 16th century. |

#48. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. Late 16th century. #48. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. Late 16th century. |

#49. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. Late 16th or early 17th century. #49. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. Late 16th or early 17th century. |

#54. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 17th century. |

#58. Plate IV. Fushimi-Yoshiro. 16th century.

#31 – Iron, inlaid in Fushimi style with brass crests and leafy scrolls : a geometrical design : Matsukawa Bishi (crests); Yaguruma (six errow ends), Tosa (oak leaves), Maru ni tachi omodaka (sagittaria), Mutsu aoi. Signed: Sadakane of Kishu.

#42 – Iron, circular, inlaid in high relief in brass with a running horse and a racing crop (repeated on the back) the stick much bigger than the horse [syntax of HLJ retained]. 16th-17th century.

#45 – Iron, small circular, the faces decorated in very low relief with small bamboos. A rim of brass in three pieces (two flanges and a rim) encircles the iron, its outside punched with circular marks in sinuous arrangement, its flanges decorated with concentric circles and with holes, also sinuously arranged, impinges upon the web by four diametrically placed trifoils and four small rounded projections in two groups alternating. 16th century.

$48 – Iron, large, the edge and part of the faces covered by a heavy brass rim chased in relief in the form of foaming waves; drops of spray inlaid brass. Late 16th century.

#49 – Iron, tachi shape (aoi). The riōhitsu of irregular outline, peculiar to Yoshiro, inlaid on one side in brass, with the story of Kosekiko and Chorio, on the other with Karashishi and a Howo, accompanied by the usual peoni and paulownia. Late 16th or early 17th century.

#54 – Iron, circular, overlaid in brass with a Howo bird, the wings and tail covering almost the whole guard. Three paulownia crests also in brass; traces of old gilding all over the brass. 17th century.

#58 – Iron, thin, circular, the seppa dai and riōhitsu outlined with brass strip punched in rope pattern, decorated on the face with two crests: maru ni mitsubiki and a maru ni kikyō crest, ise ebi, plum blossom and three stylized plants. The kikyō crest repeated twice at the back, with the same plants and three chrysanthemum blossoms. 16th century.

As we can see, the word “Ōnin” does not appear in the description of objects. They are all “Fushimi-Yoshiro”, dated from the 16th to 17th century. Two years later, in 1912, Henri L. Joly published (also a private printing in 300 copies) another tsuba book: «A descriptive catalogue of the Collection of G.H. Naunton[4], Esq.». In “Fushimi and Yoshiro styles of inlay” section on page 5 he writes:

“The above titles adopted for the sake of uniformity with previous publications although to the modern Japanese experts it seems a somewhat too wide classification. Under that heading are classified all true inlays of brass on iron, whether flat or relief, made originally at Fushimi in Yamashiro during the period circa 1585-1590, and modifications thereof. Through some early convention the thin tsuba with fairly flat inlay were called Fushimi inlay, and the name Yoshiro was reserved to those presenting larger, higher inlays, and specially to the mon zukashi tsuba, with openwork crests which were originated by Izumi no Kami Koiké Naomasa. On such pieces his name is found, sometimes genuine, sometimes forged, or merely the name Yoshiro, or that of later workers like Saburo Daiyu.

Nowadays a narrower classification has been adopted. This, rather large guards inlaid with simple, often crude, designs amongst which one finds occasionally larger decorative inlays are called Ōnin tsuba, from the name of the period 1467-1468 — a century earlier than the date at which Hedeyoshi built his castle Fushimi. They are sometimes decorated with small perforations recalling the work of swordsmiths and armourers in the previous period. Yoshiro remains the name of the mon zukashi and high relief inlays made around Kyoto, and in Kaga, some of which must have been the work of Shoami craftsmen. […]

Finally Kaga Yoshiro describes flat hirazōgan in which brass, copper, shakudō and often silver blend together in the design, etc. […] but on late tsuba of Kaga Yoshiro it is not uncommon to find shakudō or shibuichi used as ground metal. […] Finally there were numberless examples of Yoshiro work made in Kyoto, Aizu and other centres or of wholesale production up to a very late date.”[4]

This description provides a little more clarity, though it is far from being totally clear. (1) “The thin tsuba with fairly flat inlay were called Fushimi inlay”; (2) “name Yoshiro was reserved to those presenting larger, higher inlays, and specially to the mon zukashi tsuba, with openwork crests”; (3) “rather large guards inlaid with simple, often crude, designs amongst which one finds occasionally larger decorative inlays are called Ōnin tsuba”. For the sake of perspicuity, let’s leave “Kaga Yoshiro” alone. But what is the difference between Ōnin tsuba and Fushimi inlay tsuba? Any why the examples that illustrate the above statement are called Yoshiro Zōgan?

#44. Plate II. Varia. 17th century. |

#46. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#47. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#48. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#44 – Iron, with raised rounded rim, inlaid with bamboo on one side and pine on the other. 17th century.

#46 – Iron, thin, small with rounded edge, inlaid with brass dots. 17th century.

#47 – Iron, perforated with conventional holes, mokko, heart, circle, &c., and inlaid with tomoyé, rough crests, &c., brass hirazōgan. 17th century.

#48 – Iron, old piece, reduced in size and shape, with shibuichi rim, inlaid with a weeping willow on one side and peones on the other, brass in relief. 17th century.

#49. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#52. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#54. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th century. |

#61. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th-18th century. |

#49 – Iron, circular, with slightly raised edge, inlaid in relief with minogamé, waves, shells, mostly brass but partly covered with silver. 17th century.

#52 – Iron, rounded square, inlaid in hirazōgan with a coarse brass pattern of water weed (Mō) of conventional fir; perforated with four oblong holes filled with brass plugs, also perforated in designs vaguely reminiscent of crests and engraved on the surface. 17th century. Ex Hawkshaw Collection.

#54 – Iron, heavy, inlaid with a dragon, thick brass in relief, on waves and clouds, strongly chased. 17th century.

#61 – Iron, mokko, inlaid with eight maru ni ume and scrolls, brass hirazōgan. 17th-18th century.

#65. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th-18th century. |

#74. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th-18th century. |

#75. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th-18th century. |

#89. Plate II. Varia. |

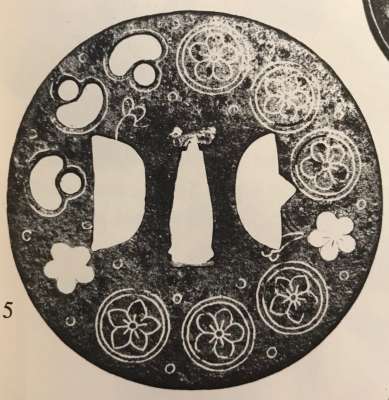

#65 – Iron, circular, with six mon. 17th-18th century.

#74 – Iron, with eight crests in brass and small tree decoration hirazōgan. 17th-18th century.

#75 – Iron, thin, the ground vermiculated, inlaid in relief with chrysanthemum blossoms, kiri crests and crosses, brass. 17th-18th century.

#89 – Iron, square with four boar’s eyes perforations inlaid with karahana and choji, brass.

#105. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan |

#107. Plate XIV. Yoshiro Zōgan. |

#115. Plate I. Yoshiro Zōgan. 17th-18th century. |

#129. Plate II. Varia. |

#105 – Iron, oblong, with hammered surface, inlaid with iris in bloom, brass.

#107 – Iron, with large riōhitsu, inlaid in brass in low relief with two ducks hishi and karakusa.

#115 – Iron, pair, circular, with narrow rim, inlaid all over with a clematis vine in bloom, brass hirazōgan. 17th-18th century.

#129 – Iron, circular, inlaid on one side with four diaper patterns and on the other with a willow tree, brass hirazōgan.

Again, not a single piece in Naunton collection is called “Ōnin tsuba”.

Four years after the Nounton’s collection, in 1916, Henri L. Joly together with Kumasaku Tomita published (limited edition of 175 copies) “Japanese art and handicraft”, a large and profusely illustrated overview of the Japanese applied arts.[5] “Swords and sword fittings” section spans from page 105 to 196. Sub-section “Inlays of Ōnin, Kyoto, Fushimi-Yoshiro, and Kaga Province” is illustrated with Plates CX, CXI, CXII.

“Ōnin guards are of iron, thin, with rounded edge, slight perforations and inlays of Shinchu (brass), Sentoku, copper, in lines, dots, or thick plates, simple designs, often Karakusa and crests only; they bear the name of the period. Kyōto inlays follow the style of the older Shoami and are in relief; the true Yoshiro work, originated by Koiké Yoshiro Naomasa in hira-zōgan technique, consists chiefly of crests, much imitated later in Kaga with poorer iron bases; the work of Nagayoshi is among the best in Heianjo zōgan, with or without sukashi.”

The only piece explicitly called “Ōnin style” is depicted on Plate CX, #128. #127 lacks attribution.

#127. Plate CX. 16th century |

#128. Plate CX. 16th century. |

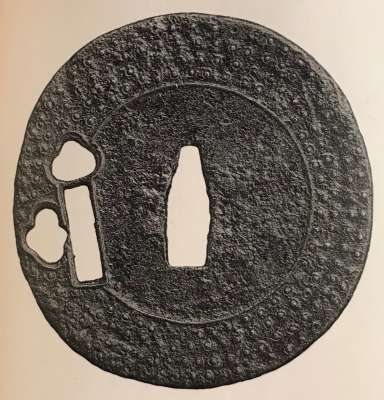

#127 – Iron, circular, the surface dotted with spots of brass in a circle, with a bridge post perforation outlined in brass. 16th century

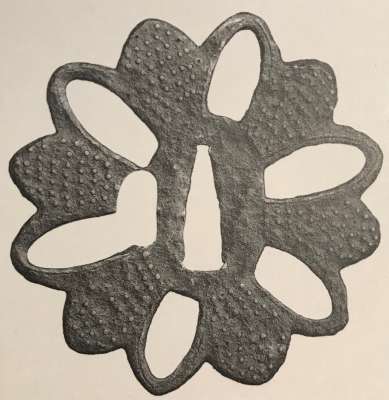

#128 –Iron, chrysanthemoid, thin guard with with alternate petals covered with brass spots. Ōnin style. 16th century.

The Field Museum’s treatise on Japanese sword-mounts published in 1923 was the first academic book on the matter[6]. Section V (pp. 53-59) is titled “Early inlays: Ōnin, Fushimi, Yoshiro, Tempō. Heianjō, Kaga, Gomoku Zōgan, Shōami, and Awa”.

“It has become customary to class under the heading Fushimi-Yashirō all iron guards decorated in flat hirazōgan of brass or in high relief of brass, which were made in the town of Fushimi in Yamashiro, where in 1589 Hideyoshi built his castle, and whither artists and artisans flocked in great numbers. However, this term includes such different types that a narrower classification is more desirable.

In the fifteenth century certain guards were made known as Ōnin tsuba, so called from the name of the period Ōnin (1467-68). The inlay is flat, either of copper, brass, or sentoku. These tsuba are usually thin in the web bounded by a rounded rim, and decorated with simple motives. An example in this collection is inlaid on either side in copper with a design of a horse’s halter. [No illustration].

The term Fushimi tsuba generally describes those guards in which the designs of flowers, scrolls, cloves, and other decorations are inlaid in flat hira-zōgan of brass, while Yoshirō is applied to those which are in higher relief and especially to the tsuba in which crests (mon) in open work and inlay form the decoration. Both of this types probably date from the sixteenth century. The name Yoshirō is derived from that of Koike Yoshirō who also signed his work Naomasa with the title Izumi-no-Kami, and who must have originated this style of decoration. M. de Tressan cites a tsuba with the signature of Yoshirō and the date 1533. It is in collection of M. Jacoby of Berlin.

#1 – … “It is of iron and carved in the round so that the solid portion forms the mitsu-tomoye… Each comma-shaped figure is inlaid in brass with an arabesque design… The inlay is flat, and fine lines of surface engraving, called kebori, bring out the veins of the leaves.”

#2 – … “is another tsuba, also of Fushimi style. It is of a size larger than ordinary… On both sides, in low relief of brass, there are designs of broken folding fans (ogi) the remaining portions which are decorated with water lines and flecks of foam chiseled in kebori.”

#3 – … “One of the earliest uses of brass inlay seems to have been of the type seen on the third tsuba in this group. Circular in form, it is divided into twelve sections, in six of which is hammered a crudely formed plum-blossom. The six other divisions are adorned with small bosses of brass in low relief, and the fields are outlined, as is the entire tsuba, with an uneven line of brass. Two tsuba of similar treatment are assigned by H. Joly and K. Tomita to the 16th century.”

#4 – …”The brass reliefs of Yoshirō guards are generally higher than those found on tsuba of the foregoing group. Conventionalized floral designs, such as the one in Plate X, Fig. 4, are common decorations. This mokkō-formed tsuba recalls the aoi form, perforated as it is with the four aoi leaves. The aoi outline is accentuated by a line of brass relief carved to represent a rope. The flowers and leaves which appear on both sides of the guard are finished with kebory chasing. Many Yoshirō tsuba are decorated with plum sprays, ginkō leaves, and blossoms of the Chinese bell-flower, kikyo (Platycodon grandiflora), which appear on this specimen.”

Even if we believe that #3 on this illustration is the Ōnin tsuba, the author does not provide us with a clear attribution. We may only guess that the enigmatic “Two tsuba of similar treatment” in the H. Joly and K. Tomita book are the ones on Plate CX, #127 and #128.

“A picture book of Japanese sword guards. Victoria & Albert Museum“[7], published in 1927 presents us with one example of the “Ōnin style” tsuba, which is this:

Floral ornament. Iron, with brass incrustation. “Ōnin” style. 16th century. V&A. M.220-1923. |

Second half of the 20th century

In 1975 The Peabody Museum collection[8] published a book of the Japanese sword guards. Here we see four tsuba attributed to Ōnin type (three pieces) and to Ōnin style (one piece). The difference between Ōnin type and Ōnin style is not explained. Three are attributed to the 16th century and one – to the 15th.

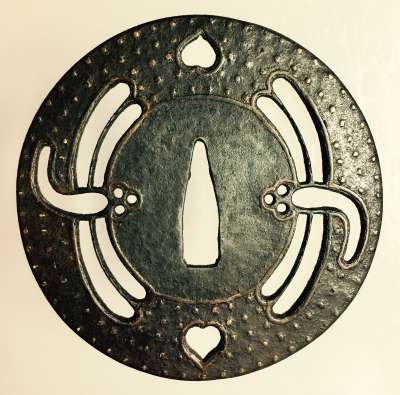

The Peabody Museum. Plate II, #5. Ōnin style, 15th century. |

The Peabody Museum. Plate II, #6. Ōnin type, 16th century. |

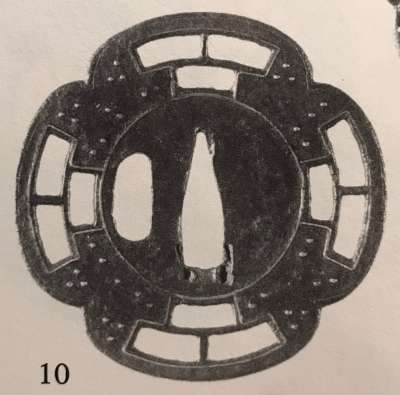

The Peabody Museum. Plate VI, #10. Ōnin type, 16th century. |

The Peabody Museum. Plate VII, #3. Ōnin style, 16th century. |

Butterfield & Butterfield[9] Auction in November, 1979 gives us three more Ōnins: one “Ōnin work” and two “Ōnin tsuba”. They all look different, though all three are attributed to the 15th century.

Butterfield & Butterfield. № 84. Ōnin work, ca. 1450. |

Christie’s November 5, 1980. #17: Ōnin tsuba, ca. 1400. |

Christie’s November 5, 1980. #18: Ōnin tsuba, ca. 1400. |

Now we come to a great source of information – The Robert E. Haynes Catalogs of the Japanese swords and sword fittings (among other ‘things Japanese’) that covers auctioning activity from 1981 to 1984 [references 11 to 19]:

Robert E. Haynes. November 1981, #1 & #2: Ōnin shinchū zōgan.

Robert E. Haynes, April 1982, #2: Ōnin example, ca. 1450. |

Robert E. Haynes, April 1982, #3: Ōnin zōgan tsuba, ca. 1500. |

Robert E. Haynes, April 1982, #15: Ōnin tsuba, ca. 1450. |

Robert E. Haynes, April 1982, #16: Damaged Ōnin example, ca. 1400. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1982, Catalog №4, #1072: Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba, ca. 1350. |

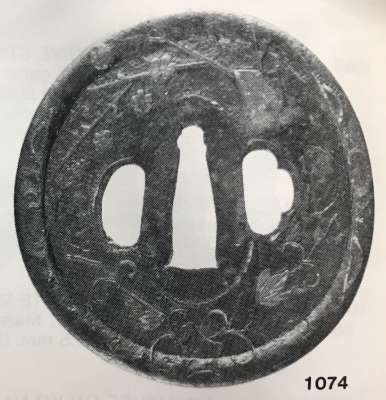

Robert E. Haynes, 1982, Catalog №4, #1074: Ōnin tsuba, ca. 1400. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1982, Catalog №4, #1099: Tanto size Ōnin example, ca. 1400. |

Then, in 1983, Robert E. Haynes published his Catalog №5[14], which provided extensive description of the early brass inlay schools and techniques. A large paragraph deals with the matter of our interest:

“Ōnin tsuba. The term Ōnin tsuba is well known. The full term for the two types of Ōnin tsuba are, Ōnin shinchū suemon-zōgan tsuba, and Onin shinchū ten-zōgan tsuba. […] Both types were made in Kyoto (prior to the making of Heianjō-zōgan tsuba in Kyoto) from Ōnin era (1467-1468) to the Tenmon era (1532-1554), a period of about ninety yers, though there are cast brass inlaid tsuba of the Edo age which seem to be the last vestiges of the school. The date of the introduction and use of brass inlay (domestic or imported) is now thought to be well before 1467, say circa 1375-1400.

Since tradition decreed that brass was first imported from China in the Eikyo era (1429-1441)…

[…] The color of the brass of the Ōnin tsuba is most important. It is rich and deep in color, not the shallow yellow color of the native metal used in the Edo age.

[…] It was the katchushi artists who first employed the new brass as decoration on their tsuba, By virtue of iron quality and tempering of the plate, the early Ōnin tsuba might better be called decorated katchushi tsuba.

Technique in application of brass to Ōnin tsuba. The brass pieces … are pre-cast in the design and shape needed. The cast pieces are then inserted into reservoirs cut to shape in the plate. The cast pieces have a smooth appearance on the surface. There are no sharp edges as might be found on carved inlay, though occasionally a few chisel marks made be made on the pre-cast piece after insertion in the plate. This technique is used for … brass inlay such as the broad areas, thin lines, roped borders, and dot inlay. The broad areas of inlay are called suemon-zōgan, and the dot inlay is called ten-zōgan. These two types constitute the two major styles of Onin tsuba brass inlay.

[…] Heianjo-zōgan … school may be considered a later development of the Ōnin shinchū-suemon-zōgan tsuba style. […] The early Heianjō-zōgan work should be considered as branch of the Ōnin school and not its full successor, for their production seems to have been parallel for a considerable period of time. Early Heianjō-zōgan work followed the design style of the Onin school, as has been stated, later they were to develop their own naturalistic and pictorial style.”

It looks like in the second half of the 15th century tsuba masters decided to decorate plane katchushi plates with brass inlay, and did it in two different styles: suemon-zōgan and ten-zōgan. For some reason these two very different techniques acquired the name of Ōnin, derived from the name of the era when these styles became popular. However, after the issue was made clear to everybody, sometimes pieces that are neither suemon-zōgan or ten-zōgan continued being attributed to Ōnin school:

Robert E. Haynes, 1983, Catalog №6, #17: Heianjō-Ōnin style work. Made in Kyoto ca. 1725. |

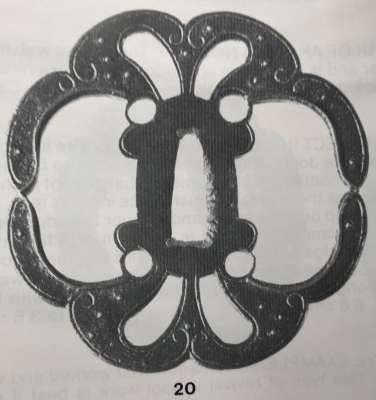

Robert E. Haynes, 1983, Catalog №6, #20: Ōnin style example, ca. 1550. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1983, Catalog №6, #23: Ōnin style example, ca. 1725. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1983, Catalog №7, #24: Important classic Ōnin example, ca. 1450. |

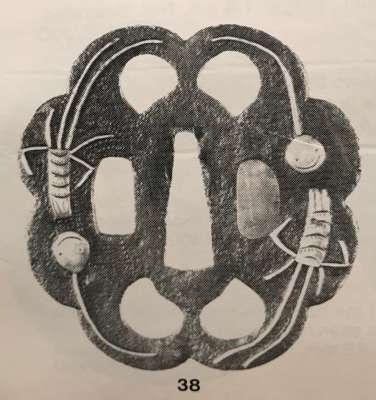

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №8, #38: Ōnin style work, ca. 1400. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №8, #38: Heianjō-Ōnin example, ca. 1750. |

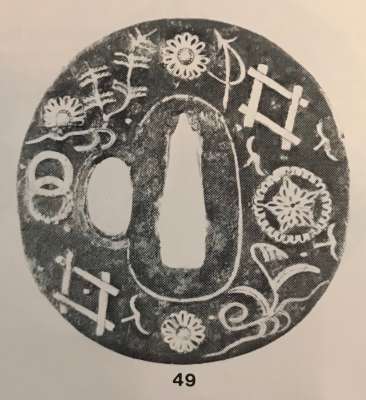

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №8, #49: Ōnin example, ca. 1450. Same at November 1981 #2. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №9, #42: Ōnin ten-zōgan style tsuba, ca. 1450. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №9, #43: Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba, ca. 1450. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №9, #57: Transitional Ōnin to Heianjō style tsuba, ca. 1550. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №9, #69: Heianjō cum Ōnin style tsuba, ca. 1750. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №10, #46: Ōnin-fu example, ca. 1500. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №10, #47: Saotome style plate with Ōnin brass inlay design, ca. 1600. |

Robert E. Haynes, 1984, Catalog №10, #51: Ten-zōgan style example, ca. 1450. |

Altogether, Robert E. Haynes catalogs illustrated 23 tsuba attributed to Ōnin school (style, type, work, example, etc.), including “ten-zōgan style”, “Heianjō cum Ōnin style”, “Ōnin-fu”, “Heianjō-Ōnin”. We saw “transitional” pieces that illustrate the theory of the Heianjō school being the heir of the the Ōnin school. We also noticed the “Ōnin” may be a style of brass inlay implemented on other school’s iron plate, which does not seem plausible taking into account that the “Ōnin” is not a single style, but a name of two different techniques.

In 1991 Graham Gemmell published a book “Tosogu. Treasure of the samurai“[20], which dedicated a few paragraphs to Ōnin tsuba, and provided a few excellent illustrations:

“Onin. In simple terms Onin works are decorated Ko-Katchushi tsuba. … But, not content with iron alone, they began to decorate it with what was, in the early Muromachi period, a rare and valuable metal, brass. The Onin workers cut the design into the iron, using narrow channels, cast the brass, piece by piece, and then hammered it into the iron plate as though they were putting together a jigsaw. When complete the tsuba would be black lacquered exactly as the plain iron ones had been, the brass shining dully through it in a way that fulfilled the goal of shibui or restrained elegance.”

“There were three general types of brass inlay. The first used strips of brass to highlight the design in the iron. The second used inlayed strips of different widths and some solid castings to produce an intricate floral design covering most of the plate. The third technique was dot inlay, where small circular ‘nails’ of brass were hammered into holes drilled into iron.”

“… The Onin School was so short lived (first half of Muromachi period) that any Onin work is rare, and good pieces extremely rare. As well as being so closely associated with the Ko-Katchushi School they were linked to the Kamakura School, which made similar iron tsuba without the brass inlay, and to the Heianjo School which superseded them.”

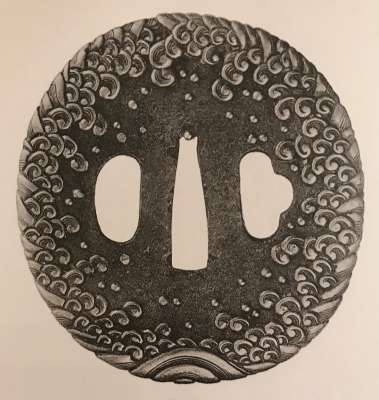

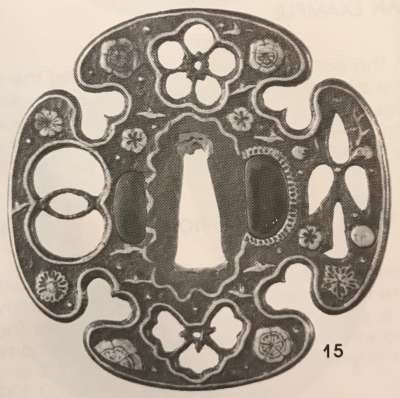

Tosogu… Page 142, #15. Cast brass floral inlay. Early Muromachi period. [2nd type Ōnin tsuba] |

Tosogu… Page 142, #16. Brass dot inlay. Middle Muromachi period. [3rd type Ōnin tsuba] |

Tosogu… Page 142, #17. Cast brass strip inlay. Early Muromachi period. [1st type Ōnin tsuba] |

Then, the book provides certain thoughts regarding the origins of the Heianjō and Yoshiro schools that suggest so much needed demystification of the “Fushimi-Yoshiro style of inlay”:

“The Heianjo School produced tsuba from the mid-Muromachi period to the late Edo period and this longevity nearly ruined their reputation. As taste declined, and as Westerners arrived wanting souvenirs, their tsuba became more and more highly decorated, eventually becoming mere kanome, mass produced at Yokohama for quick sale to foreigners. […] Developing out of the Onin School, and initially using cast brass, they produced tsuba with more fluid and naturalistic designs, less formal than the Onin and much more individual.

In early work there are two main types of design, pictorial and patterned, the latter similar to Onin work, using sukashi openings as well as floral inlay. Pictorial work was very simple at first using one motif and inlay of brass only. In late Muromachi period a little silver was used too, and then, in the Momoyama and Edo periods, the Heianjo School bloomed into flat inlay as well as raised inlay. Copper and gold were added to the repertoire, inlay began to cover more and more of iron and signatures appeared. Muromachi period tsuba can be recognized by the thinness of the iron, the relatively small amount of inlay, the simplicity yet effectiveness of the design, and the fine colour of the brass contrasting with the polished darkness of the iron.

It is important to note that examples of Mid-Muromachi mon-sukashi tsuba show that it was the inventive Heianjō School that started the design and the later Yoshiro School that popularized it.”

Tsuba illustrated on #15 and #16 on page 142 at “Tosogu…” confirms the statement of Robert E. Haynes in Catalog №5 regarding two distinct types of Ōnin tsuba: Ōnin shinchū suemon-zōgan and Ōnin shinchū ten-zōgan. However #17 does not have any reference to the examples above. All three tsuba in focus can be found in other reference books:

#15 is also illustrated at Japanese Works of Art, Part II: Swords and Fittings, Netsuke and Lacquer. Sale LN4670 “SUZUKI”. Sotheby’s, London on November 17, 1994 under №527: “A rare large early Ōnin tsuba. Early Muromachi period (early 15th century). Of circular form with rounded raised rim, inlaid with trailing flowers in brass, over two udenuki-ana. Diameter 92 mm. Tomobako bearing hakogaki by Masayuki Sasano.”[27]

#16 is also illustrated at Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A. Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections. Sotheby’s, London, Thursday 10 April 1997 under №12: “An Ōnin tsuba, middle Muromachi period. Of rounded mokkō form, the thin plate pierced with ju (ten) character, the sukashi openings outlined in brass and the rim and cross applied with brass ten-zogan (nail-heads). 83 x 81 x 2.5 mm. Tomobako with Masayuki Sasano hakogaki, with rating Shu.”[32]

#17 is also illustrated at Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A. Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections. Sotheby’s, London, Thursday 10 April 1997 under №8: “An unusually early Ōnin tsuba. Early Muromachi period (1393-1453). Of circular form, pierced with an eight-pointed star, inlaid with lines on both sides in brass and on the rounded rim with formal karakusa, the plate bearing traces of original lacquer. Diameter 85 mm, thickness at center 3.7 mm. Ex Masayuki Sasano.”[32]

Here we see that Masayuki Sasano himself attributed all three above pieces to the Ōnin school. Now our perception is getting shape. Further understanding of the Ōnin tsuba came from various sources. Thanks to the progress of technology, from 1991 on we almost exclusively see high quality color photographs, with few exceptions.

Here we have nine Ōnin tsuba from Compton Collection, Part I[21], II[22], and III[23], 1992:

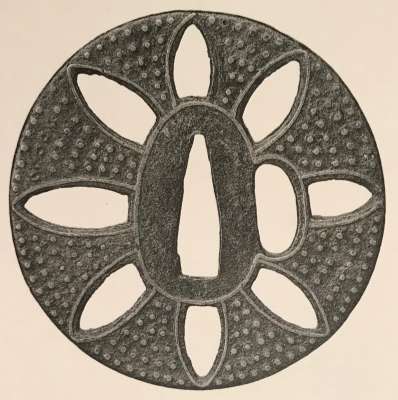

Compton Collection, Part I, #7: An Ōnin school tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1500). |

Compton Collection, Part II, #20: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1400). |

Compton Collection, Part II, #21: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1550). |

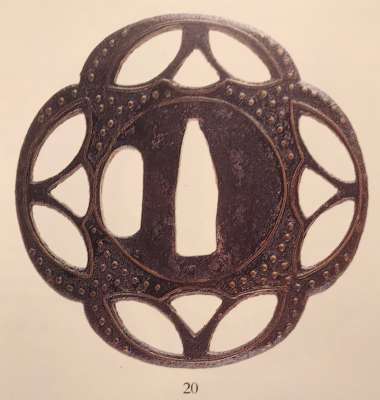

#7 – The iron plate is of flowerhead shape with each of the fourteen petals alternating between solid and openwork. The apertures are outlined in inlaid brass as is the seppa-dai and hitsu-ana. The reminder of the plate is similarly inlaid with plum flowers, birds, dots of dew, Genji mon and sambiki mon. 87 mm x 85 mm x 3.5 mm. $2,640[21].

#20 – The thin, four-lobed iron plate is inlaid with brass dots (tenzogan) and brass wire, lines with four openwork areas of three leaves each. 72 mm x 71 mm x 3.0 mm. $3,080[22].

#21 – The round iron plate has an openwork design of checkerboard pattern, inlaid in brass, with three bars in a circle (kiki maru) the family crest of the Abe and other daimyo families. The plate has brass inlay of chrysanthemums, leaves and wire lines. The square hitsu-ana are original. 82 mm x 81 mm x 4.0 mm. $1,760[22].

Compton Collection, Part II, #22: An Ōnin sukashi tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1450). |

Compton Collection, Part II, #21: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1400). |

Compton Collection, Part II, #21: A classic Ōnin brass inlay tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1450). |

#22 – The four-lobed mokko form iron plate is pierced with four handle-shaped (kan) peirced areas which are outlined in brass wire on both sides, and with double and single rows of nail-head (tenzogan) brass dots. The center of the plate has a circle of brass wire inlaid on each side. The peirced hitsu-ana of large rectangular shape is typical of the Muromachi period. 75 mm x 73 mm x 2.2 mm. In wood box inscribed by Sato Kanzan dated Showa 50 (1975). Tokubetsu kicho certificate #279, dated Showa 48 (1973). $1,430[22].

#24 – The thin, round iron plate is decorated on both sides in brass dot inlay (tenzogan) and thin wire inlay. The hitsu-ana are original. Diameter 76 mm, thickness 3.0 mm. Three rows of dots characterize early inlay style whereas later examples (middle to late Muromachi period, 1450-1550) have four or five rows of dots. $1,430[22].

#25 – The iron plate is inlaid on each side with cast brass and brass wire depicting mandarin orange (tachibana) and the hiki (sanbiki) crest (mon) employed by Sakuma daimyo of Owari. The remaining inlay of brass depicts chrysanthemums, birds and dots of dew. 85 mm x 84 mm x 2.5 mm. $6,050[22].

Compton Collection, Part III, #7: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1450). |

Compton Collection, Part III, #8: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1450). |

Compton Collection, Part III, #9: An Ōnin style tsuba, Muromachi period (circa 1450). |

#7 – The thin round iron plate is of four-lobed shape. The surface of both sides is inlaid with four rows of brass dots and circle of brass wire near the center of the plate. Diameter 81 mm, thickness 3.0 mm. $605 [23].

#8 – The thin oval iron plate is inlaid with brass in a design of family crests, gourd vines, flowers and plants. 74 mm x 72 mm x 2.5 mm. Provenance John Harding, London, not sold (est. $1,000-1,500)[23]..

#9 – The thin round iron plate has four openwork areas, each with a central bar. The flat plate areas are decorated in brass with family crests and floral designs. The hitsu-ana are original. Diameter 85 mm, thickness 4.0 mm. Wood box with inskription bt Torigoye Kazutaro, dated Showa 40 (March 1965). $880[23].

The next piece of evidence is provided by Lundgren Collection[24], [25].

Lundgren Collection: A large Ōnin tsuba, Muromachi period (16th century). |

Lundgren Collection: A large mokkogata Ōnin tsuba, Momoyama period (late 16th – early 17th century). |

Lundgren Collection: A circular iron Ōnin tsuba, Late Muromachi period (16th century). |

Lundgren Collection: A mokkogata Ōnin iron tsuba, Late Muromachi period (late 15th – early 16th century). |

Numbers on photographs represent Christie’s catalogue[25]. The second number in parenthesis below refer to Lundgren Collection 1992 edition[24].

#5 (132) – Decorated in brass zogan with pine nidles, mon including kaminari (thunder), kiku and ido [a well], rounded mimi 83 mm, thickness 3 mm. 1992 edition attributes this tsuba to Heianjō school.

#6 (2) – Decorated with band of dots [hoshi] representing stars and a circle in brass uchikaeshi mimi. 92 mm x 8.65 mm, thickness 4 mm (at rim). $1,725.

# 7 (1) – The rim decorated with a wide band of brass tenzogan and pierced with stylized monkeys (kukurizaru) in ko-sukashi, square mimi. Diameter 74 mm, thickness 2 mm (at rim). $977.

10 (3) – It’s four corners pierced as inome, each lobe of the mokko pierced in ko-sukashi with stylized Genji-mon, a fan, cherry and plum blossom, the plate inlaid with flowerheads, mitsuhiki-bishi and scrolling foliage, square mimi. 83 mm x 3 mm. $1,840.

A look alike Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba with kukurizaru (knotted monkey doll, monkey with bound feet and hands, though Sasano describes it as a ‘self-righting monkey’, kind off roly-poly toy) motif presented at The Henry D. Rosin Collection[26].

Page 22, #9. Onin. A circular iron tsuba in negative openwork with a design of three monkey toys, the plate further decorated with four rows of ten-zogan. Muromachi period. 87 x 87 x 2 mm. Certificated box by Sasano Masayuki. The same tsuba can be found at “Tsuba” by Günter Heckmann.[28]

Nowadays

To finish the essay about Ōnin tsuba, I would like to cite a book “Tsuba. An Aesthetic Study” by Kazutaro Torigoye and Robert E. Haynes, recently re-printed by the Northern California Japanese Sword Club (NCJSC)[29]:

“The term Ōnin tsuba is well known. The full term for the two types of Ōnin tsuba are Ōnin shinchū suemon-zōgan tsuba and Ōnin shinchū ten-zōgan tsuba. Both types were made in Kyōto (prior to the making of Heianjō-zōgan tsuba in Kyōto) from Ōnin era (1407-1468) to the Temmon era (1532-1554), a period of about ninety years”. [This is obviously a typographical error, as the Ōnin era covered the period from 1467 to 1469. The Temmon (or Tenbun) era spanned from 1532 through 1555]. “Since tradition decrees that brass was first imported from China in the Eikyō era (1429-1441), it is natural that it should be employed in the decoration of tsuba shortly after”. One would expect then that production of Ōnin tsuba started in 1429; however, it was started earlier: “There was a native alloy in use prior to the Eikyō era. It was a combination of yamagane and zinc”. The reason why the raw, unrefined copper (“mountain copper”) is called here by its Japanese name (‘yamagane’), whether zinc is called ‘zinc’, remains unclear. “It closely resembled the imported brass. […] The color of the brass of the Ōnin tsuba is most important. It is rich and deep in color, not the shallow yellow color of the native metal used mostly in the Edo age. […] It is logical to suppose that these tsuba were first made in Kyōto because the imported brass is thought to have been brought to the port of Sakai (near present Ōsaka), and then carried to the capital, Kyoto. It was the katchūshi artists who first employed the new brass as decoration on their tsuba. …the early Ōnin tsuba might better be called decorated katchūshi tsuba. […]

Ten-zōgan:

In the past it was thought that all Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba were the earliest types of brass inlay. Actually only one style dates from the earliest period. The early style has four rows of brass dots closely spaced. They form concentric circles surrounding the rim on the web of the plate. […] In the later style there are but three rows of dots with more space between them than is found in the early style.

Technique in application of brass to Ōnin tsuba:

The brass pieces used as the decoration on Ōnin tsuba are pre-cast in the design and shape needed. The cast pieces then inserted into reservoirs cut to shape in the plate. The cast pieces have a smooth appearance on the surface. There are no sharp edges as might be found on carved inlay, though occasionally a few chisel marks may be made on the pre-cast piece after insertion in the plate. This technique is used for all parts of the Ōnin brass inlay such as broad areas, thin lines, roped borders, and dot inlay. The broad areas of inlay is called suemon-zōgan and the dot inlay is called ten-zōgan. The two types constitute the two major styles of Ōnin tsuba brass inlay.”

And then the authors describe the difference between the Ōnin tsuba and the Heianjō tsuba, shedding light into one of the darkest areas of tsubology.

“Difference between Ōnin and Heianjō-zōgan tsuba:

The Heianjō zōgan style is not pre-cast. The decoration is cut from sheets of brass, inserted into the reservoirs in the plate, then the design is carved on the insertion. Thus it is quite easy to differentiate between the two styles even though the designs may be very similar. One note of caution; in some cases it will be found that these two techniques have been applied to the same tsuba. In this case the tsuba in question will usually be early Heianjō-zōgan work, rather than late Ōnin. The Heianjō-zōgan school is thought to have come from the Ōnin school and that they used the Ōnin style in their early work. Tsuba of small size are rare in Ōnin work but rather common in Heianjō-zōgan pieces.”

The table composed of [29] data with modifications:

| Feature | Ōnin tsuba | Heianjō tsuba |

| Shape | Round, rounded square, oval, kikuka-gata, and other shapes | Round, oval |

| Thickness | 2.5-4.0 mm | 3.0-4.5 mm |

| Seppa-dai | Surrounded by thin inlaid brass wire | |

| Hitsu-ana | Added later or on small size pieces | Kyo-sukashi style |

| Edge | Round or kakumimi koniku | Round or nadekaku-gata (rounded square) |

| Forging | Well forged, soft iron common, hard iron rare. Hammer marks | Usually soft iron, smooth surface. |

| Design | Branch of the orange, utensils, animals, plants, mon, geometrical patterns. Edge and perforations surrounded by inlaid strips of brass or roped design. | Plants, animals, human figures and picturesque designs. Naturalistic, later realistic. |

| Signature | None | Usually none. Rare: Nagayoshi, Kaneshige, Yukihisa, Yoshiiye, Yoshihisa, Shigemitsu, Shigeyuki, Kanesada, Munetoshi, Matayoshi, Masamoto. |

| Openwork | Mitsu uroko, linked circles, mon, butterfly, dragonfly, mushrooms. | |

| Inlay | Pre-cast brass ten-zōgan or suemon-zōgan | Raised or flat; Cut brass. Later – silver, gold, copper. |

The latest detailed description of the Ōnin tsuba has been provided by Gary D. Murtha[30]. “Onin is a name tsuba collectors have used to classify a certain style of tsuba created during the Onin era (1407-1468). [We can see that Mr. Murtha copied the typo in the Onin era dates from “Tsuba. An Aesthetic Study”]. The earliest Onin tsuba date to early Muromachi period. The first Ōnin tsuba were thin iron plates, without hitsu-ana, and with ten-zogan (brass dot inlay). […] The next design phase, of Onin tsuba, was the addition of small sukashi crests and symbols with most outlined with thin brass inlay. Soon, the addition of circular, sen-zogan trim (brass fine line inlay) appeared around hitsu-ana and seppa-dai. The next phase was the addition of brass suemon-zogan (cut sheet inlay) of leaves, vines, crests, flowers, bamboo, pine needles and the like”. It is hard to tell why Mr. Murtha divided development of different Ōnin-zōgan styles into historically consequent phases; I did not manage to find any reference in support of this understanding.

Conclusion

The term ‘Ōnin tsuba’ or even Ōnin-tsuba (per Markus Sesko) was invented by tsuba collectors in the beginning of the 20th century. For some unclear reason this term was applied to two distinct spices of brass inlaid tsuba: one with the ten-zōgan and another with the suemon-zōgan. It is likely that both types of tsuba were manufactured at about the same time, from beginning of the 15th to the middle of the 16th century, during entire Muromachi period, in Kyoto and surroundings. The ten-zōgan tsuba can be seen as an extension and heir of the Katchushi school, which died in Momoyama period without passing its technique to posteriority. The suemon-zōgan type, by contrast, appeared from the nowhere, and survived in its heirs: Kaga, Heianjō, and Higo schools. Terms ‘Ōnin style’ and ‘Ōnin type’ do not make much sense because it not one style or type, but two. It is also clear that shortening of the terms ‘Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba’ and Ōnin suemon-zōgan tsuba’ to just ‘Ōnin tsuba’ produced a lot of confusion and shall only be practiced when referring collectively to both types of tsuba.

Looking at the age attribution of ten-zōgan tsuba in the examples reproduced in this essay, one cannot find any correlation between the number of dot inlay rows and the age, neither we see definite consistency between the age and presence/absence of openwork (sukashi). Probably the more such a tsuba resembles a Katchushi tsuba, the older the specimen. Dating Ōnin tsuba of any style at before circa 1400 seems doubtful. Traces of black lacquer found on Ōnin tsuba must be preserved by all means; chemical or mechanical removal of lacquer may be considered a grave mistake.

Finally, in tsuba description I would recommend using either the romanized Japanese terminology (such as ‘sukashi’, ‘zōgan’, ‘mokko-gata’) or English terminology (such as ‘openwork’, ‘inlay’, ‘four-lobed or quatrefoil form’), rather than using the mix of the two. The reader would agree that phrases like “maru ni mitsubiki and a maru ni kikyō crest, ise ebi, plum blossom and three stylized plants” sound funny.

Ōnin tsuba in this collection:

№330. Ōnin ten-zōgan tsuba of nade hakkaku form. Muromachi period. |

№317. Ōnin suemon -zōgan tsuba. Genji-mon, family crests, plants, and vines. Muromachi period. |

[1] Okabe-Kakuya. Japanese sword guards. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In cooperation with the department of Chinese and Japanese art; – 1908.

[2] Markus Sesko. Encyclopedia of Japanese Swords. Print and publishing: Lulu Enterprises, Inc., – 2014.

[3] Japanese sword-mounts. A descriptive catalogue of the collection of J. C. Hawkshaw, Esq., M.A., of Hollycombe, Liphook. Complied and illustrated by Henri L. Joly. London, – 1910.

[4] Japanese Sword Fittings. A descriptive catalogue of the Collection of G.H. Naunton, Esq., completed and illustrated by Henri L. Joly, – 1912.

[5] Henri L. Joly and Kumasaku Tomita. Japanese art and handicraft. An illustrated record of the loan exhibition held in aid of the British Red Cross in October – November, 1915. London, Yamanaka & Co, 1916.

[6] Japanese sword-mounts in the collection of Field Museum by Helen C. Gunsaulus, Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology. 61 plates. Berthold Laufer, Curator of Anthropology. Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 216, Anthropological Series, Volume XVI; Chicago, 1923.

[7] A picture book of Japanese sword guards. Victoria & Albert Museum, 1927.

[8] The Peabody Museum collection of Japanese sword guards with selected pieces of sword furniture, by John D. Hamilton. Salem, MA, 1975.

[9] Butterfield & Butterfield. IMPORTANT JAPANESE SWORDS, SWORD FITTINGS AND ARMOR. Auction Monday, November 19th, 1979. Sale # 3063.

[10] Important Japanese Swords and Sword Furniture and Works of Art. November 5, 1980, sales “Kotetsu”. New York, Christie, Manson & Woods International Inc., 1980.

[11] Highly important Japanese swords and kodogu. San Francisco, November 13-15, 1981. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[12] Important Japanese kodogu, gaiso and works of art. San Francisco, April 9-11, 1982. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[13] Important Japanese tsuba, early iron and kindo examples. San Francisco, November 1-28, 1982. Catalog #4. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[14] Fine Japanese tsuba, fittings, woodblock prints, netsuke, inro and books on swords and tsuba. San Francisco, March 1-27, 1983. Catalog #5. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[15] Important tsuba, menuki, bokuto, woodblock prints, koshirae, sword pistol and kana mono. San Francisco, June 1-26, 1983. Catalog #6. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[16] Masterpiece tsuba and kodogu from the Hans Conried and Alexander G. Mosle collections. Important woodblock prints by Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige, Yoshida and other masters. San Francisco, September 1-25, 1983. Catalog #7. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[17] Important signed Shoami tsuba, collection of fine menuki, kozuka, and fuchi-kashira, interesting and important 19th and 20th century woodblock prints and books. San Francisco, January 16 to February 12, 1984. Catalog #8. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd.

[18] Catalog #9. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd. Masterpiece and highly important tsuba, menuki, and fuchi-kashira from eminent collections in America, England, France, and Japan. San Francisco, May 8-12 and May 21-27, 1984.

[19] Catalog #10. Robert E. Haynes, Ltd. Important tsuba, menuki, kozuka, fuchi-kashira, kabuto, reference books and woodblock prints. San Francisco, September 10 – October 14, 1984.

[20] Tosogu. Treasure of the samurai. Fine Japanese Sword Fittings from The Muromachi to The Meiji Period, by Graham Gemmell. Sarzi-Amadè Limited, London, 1991. An exhibition held in London from 21st March to 4th April 1991.

[21] Japanese Swords and Sword Fittings from the Collection of Dr. Walter Ames Compton (Part I). Specialists in charge: Sebastian Izzard and Yoshinori Munemura. Christie’s, New York, March 31, 1992.

[22] Japanese Swords and Sword Fittings from the Collection of Dr. Walter Ames Compton (Part II). Specialists in charge: Sebastian Izzard and Yoshinori Munemura. Christie’s, New York, October 22, 1992.

[23] Japanese Swords and Sword Fittings from the Collection of Dr. Walter Ames Compton (Part III). Specialists in charge: Sebastian Izzard and Yoshinori Munemura. Christie’s, New York, December 17, 1992.

[24] JAPANESE SWORD-FITTINGS & METALWORK IN THE LUNDGREN COLLECTION. Published by Otsuka Kogeisha, Tokyo 1992.

[25] The Lundgren Collection of Japanese Swords, Sword Fittings and A Group of Miochin School Metalwork. Christie’s Auction: Tuesday, 18 November 1997, London. Sales “GOTO-5881”. Christie’s, 1997.

[26] The Henry D. Rosin Collection of Japanese Sword Fittings. An exhibition held at Syz Limited, London from 11th to 25th June 1993; Catalogue by Patrick Syz.// Published by Syz Limited, London, 1993.

[27] Japanese Works of Art, Part II: Swords and Fittings, Netsuke and Lacquer. Sale LN4670 “SUZUKI”. Sotheby’s, London on November 17, 1994.

[28] Tsuba. Text and Photography: Günter Heckmann. Printed in Germany by Offizin Anderson Nexö GmbH, 1995.

[29] “Tsuba. An Aesthetic Study” by Kazutaro Torigoye and Robert E. Haynes, from the Tsuba Geijutsu-kō of Kazataro Torigoye, edited and published by Alan L. Harvie for the Northern California Japanese Sword Club (NCJSC) 1994-1997, Second Printing November 2007.

[30] Japanese Sword Guards. Onin-Heianjo-Yoshiro. Gary D. Murtha. GDM Publications, 2016.

[31] Robert E. Haynes. Study Collection of Japanese Sword Fittings. Nihon Art Publishers, 2010.

[32] Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A. Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections. Sotheby’s, London, Thursday 10 April 1997.