Woodblock print album of thirteen prints, ōban, nishiki-e.

Artist: Chōkyōsai Eiri [鳥橋斎 栄里] (Japanese, fl. c. 1789 ~ 1801 ).

Models of calligraphy (Fumi no kiyogaki), New Year 1801. This title is taken from Chris Uhlenbeck’s Japanese Erotic Fantasies Sexual Imagery of the Edo Period. — Hotei Publishing, 2005, ISBN 90-74822-66-5):.

A detailed description of the album can be found at The Complete Ukiyo-e Shunga №9 Eiri, 1996, ISBN 4-309-91019. Most of the edition is in Japanese, though Richard Lane writes a section in English: Eiri: Love-letters, Love Consummated: Fumi-no-kiyogaki. The article starts with the following statement:

“Why all the fuss about Sharaku? Because he is so “mysterious”? No, not at all: because he is such a good artist. But Sharaku is not the only great yet enigmatic ukiyo-e artist and I propose to resurrect here one of his important contemporaries who has been all too long neglected: Chōkyōsai Eiri. As with many of the notable ukiyo-e masters, nothing is known of Eiri’s biography. All we can say is what we learn from his extant prints and paintings: that he flourished during the second half of the Kansei Period [1789-1801]; and that he was a direct pupil of the great Eishi – who, being of eminent samurai stock, may well have attracted pupils of similar background.”

Another citation from Japanese Erotic Fantasies:

“This album is one of the boldest sets of ōban-size shunga known, The first edition contains thirteen instead of the customary twelve designs”.

Here I present all thirteen prints, though the edition I bought in Kyoto in 2014 contained only twelve. The thirteenth print was purchased later in the United States (sheet №12).

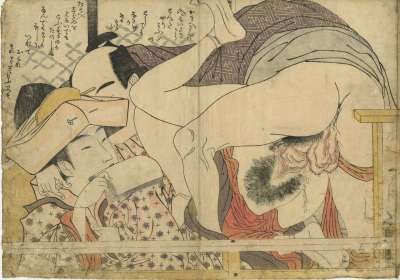

№1: “…one of the most exotic scenes in all shunga. A Dutch kapitan is discovered coupling with a lovely Japanese courtesan, beside a large window opening upon a garden…”.

№2: “…a fair young harlot is seen masturbating with a grinding-pestle – a man watches intently from under bedding.” [I have two specimens of this design; the one from album is more soiled but less faded].

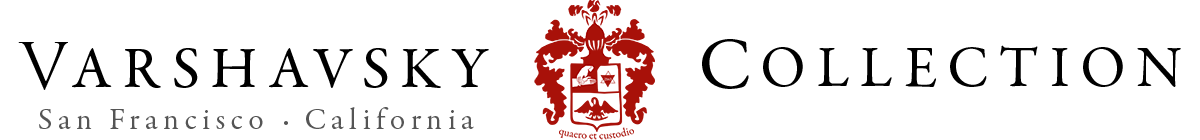

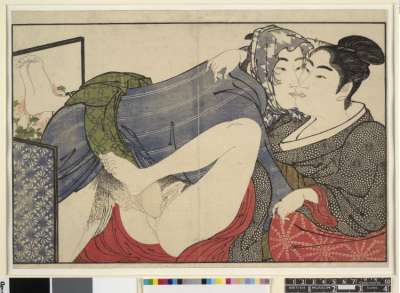

№3: “…the artist has effectively contrasted the lovers by depicting the man’s face as seen through the geisha’s gauze skirt. […] we are impressed more by strikingly elegant composition, the dramatic coloring, rather than feeling any great urge to participate in the energetic proceedings…”

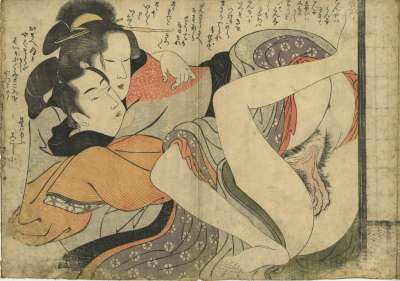

№4: “This scene is a most straightforward one, featuring the standard Missionary Position [capitalization by R. Lane].; but withal, the contrast of the young and naked, secret lover and the richly-clothed courtesan amid luxurious bedding…”

№5: “In a striking lesbian scene (which has no equivalent in Utamaro, and is, incidentally, often omitted in later editions of this album), the girl at left prepares to receive the harikata (dildo) worn by the older girl at right (who holds a seashell containing lubricant).”

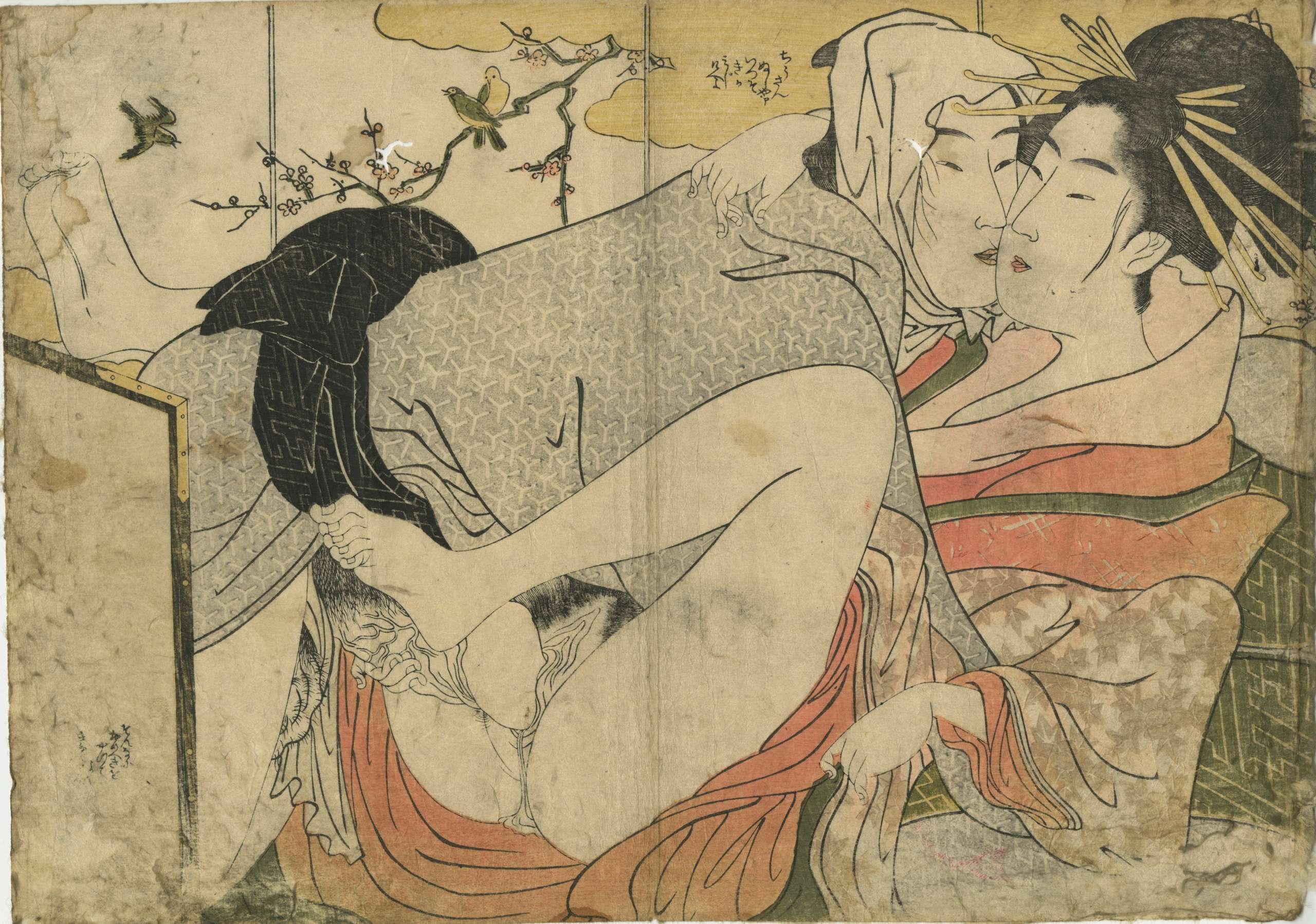

№6: “In the first appearance of a matronly heroine in this series, we find a widow – with shaven eyebrows and clipped hair – sporting with a handsome yound shop-clerk, mounting him with all her might.”

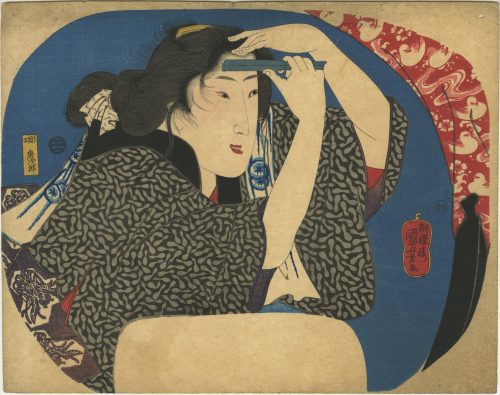

№7: “… lady of samurai court: here, shown taking advantage of an official outing to temple and theatre, to rendezvous with a secret lover on a teahouse balcony.” R. Lane considers this design the least successful in the series, especially in comparison with the same theme by Utamaro: “Utamaro female is almost ferocious in her lust for sexual gratification”, which does not sound true to me. See Utamaro’s sheet №5 from the album Utamakura (歌まくら, Poem of the Pillow) [courtesy The British Museum without permission]:

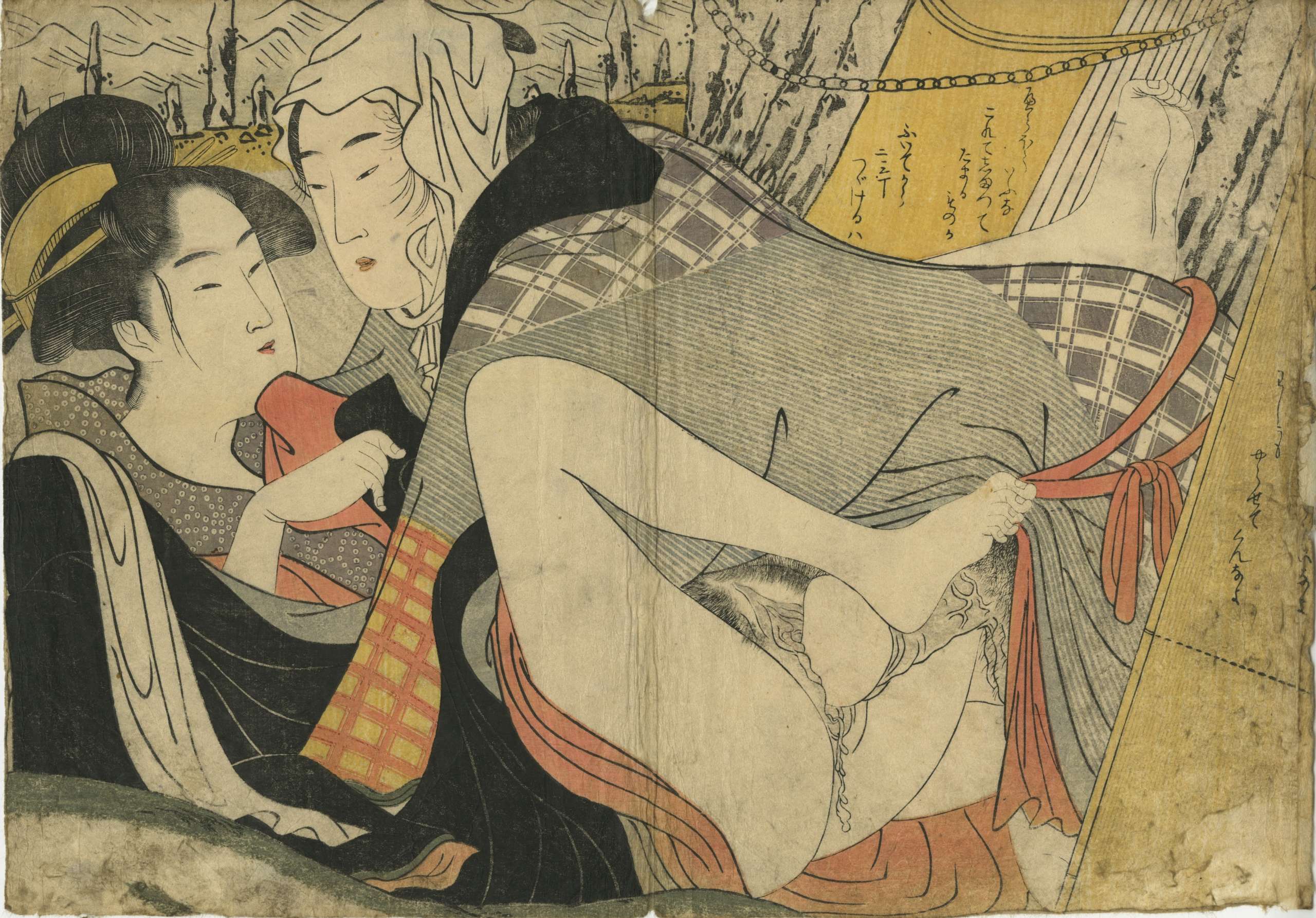

Then, as Richard Lane states, “we are flung suddenly to the bottom rung of Edo society”:

№8: “Here we find a fair yotaka (‘night-hawk’, e.i. streetwalker) accommodating a lusty client in a lumberyard by the bank of the Sumida River”.

№9: ‘… a slightly plump harlot of the lower class receives a night visit from her lover, whose naked form she tries to cover with a cloak.”

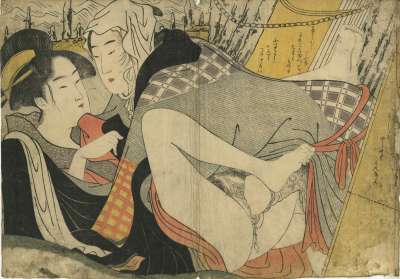

№10: “…likely maidservant and lackey – are depicted in bath-room, their passions are all too obviously fired by steaming water.”

№11: “…this scene of courtesan and secret lover ranks high not only in Eiri’s œuvre but also in the annals of the ukiyo-e genre itself. Both design and colouring are impeccable and, for this period, there is nothing even in the work of great Utamaro that really surpasses it.” Again, a doubtful statement, however, this is Utamaro’s design for the reader to judge:

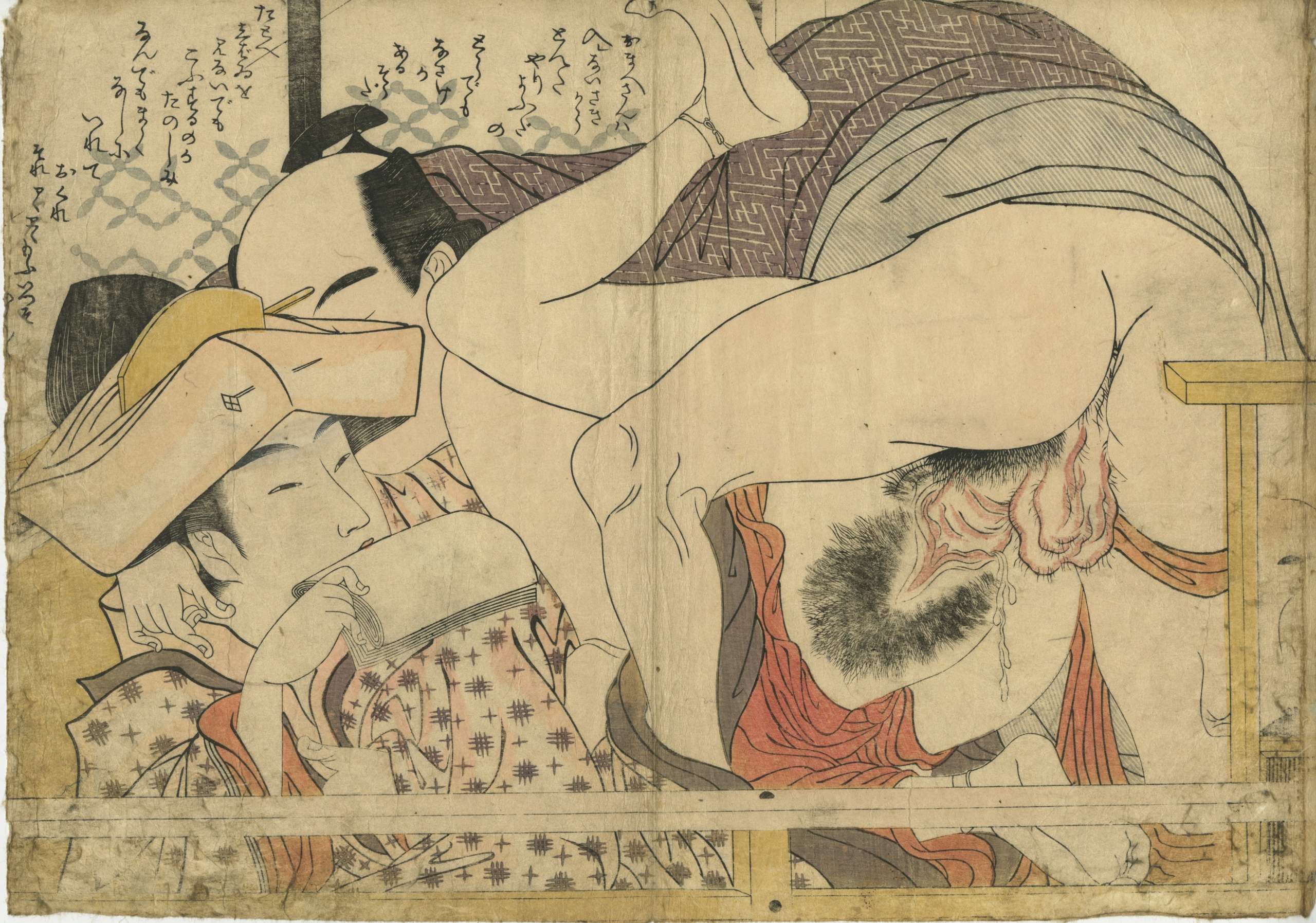

The last design in my album is this:

#13: In most reference books it goes under number 13, and we will assign this number to the sheet. “The final scene of the album features naked participants, probably samurai man and wife. The print is rather subdued in tone and colour, if not in the degree of the passion displayed…”

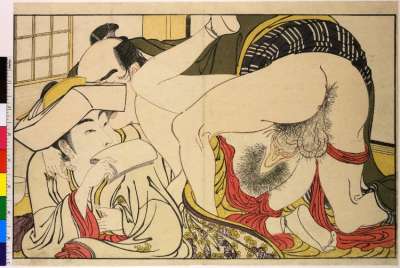

An additional sheet, acquired separately from a reputable dealer in New York, is usually listed as №12:

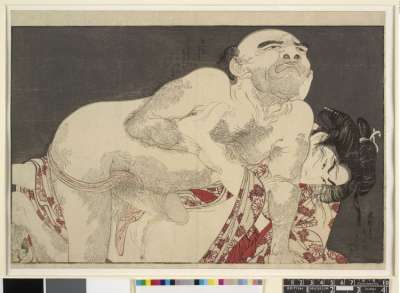

№12: “One might think that Eiri has reached his peak with the preceding plate 11 – and indeed he has, in both esthetic and erotic terms. But the album is not yet finished, and the next scene lends a needed variety to the series, a slightly comic tableau featuring a middle-aged lackey attempting to forcibly seduce a servant girl of the same domicile”. Utamaro’s design, that inspired Eiri is here:

All descriptions are taken from Richard Lane’s article at The Complete Ukiyo-e Shunga №9 Eiri, 1996. He concluded: “…Eiri’s erotic series represents a major contribution to shunga art towards the close of ukiyo-e “Golden Age”. In part inspired by Utamaro’s classic album, this series withal constitutes a unified and original achievement, providing a cumulative effect of gracefully elegant yet glowing eroticism, which remains in the mind’s eye long after the pictures themselves are far away.”

I only would like to mention here that in several reference sources this album goes under name of Eisho; unfortunately, this mistake is reproduced at www.ukiyo-e.org, which miraculously shows exactly my print, but under the wrong name of the artist. The same mistake can be found at Shunga. The art of love in Japan. Tom and Mary Anne Evans. Paddington Press Ltd., 1975. ISBN 0-8467-0066-2; plates 6.74-6.77: Chōkyōsai Eishō, c. 1800. Even the British Museum edition of 2010 gives the same erroneous attribution: Chōkyōsai Eishō (1793-1801); they provide the following translation of title: “Clean Draft of a Letter” [see: Shunga. Erotic art in Japan. Rosina Buckland. The British Museum Press, 2010; pp. 110-112]. To the honour of the British Museum, I must admit that they have corrected themselves in Shunga. Sex and pleasure in Japanese art. Edited by Timothy Clark, et al. Hotei Publishing, 2013. Now, they say Chōkyōsai Eiri (worked c. 1790s-1801); they also provide a new title: “Neat Version of the Love Letter, or Pure Drawings of Female Beauty”. I have already mentioned Richard Lane’s version of title: “Love-letters, Love Consummated”, and Chris Uhlenbeck’s “Models of calligraphy”. In poorly designed and printed Shunga. Erotic figures in Japanese art. Presented by Gabriele Mandel. Translated by Alison L’Eplattenier. Crescent Books, New York, 1983, the artist is named Shokyosai Eisho (beginning of the 19th century); title provided: “Models of Calligraphy”. Correct attribution to Chōkyōsai Eiri also can be found at Poem of the pillow and other stories by Utamaro, Hokusai, Kuniyoshi and other artists of the floating world. Gian Carlo Calza in collaboration with Stefania Piotti. Phaidon Press, 2010; though the title is translated as “Clean Copy of Female Beauty”.