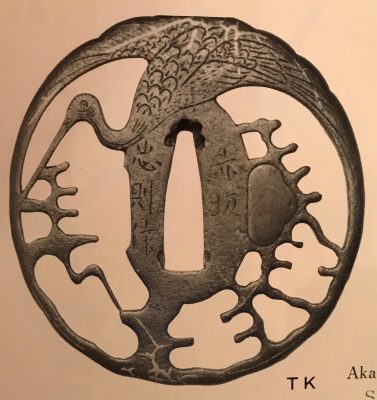

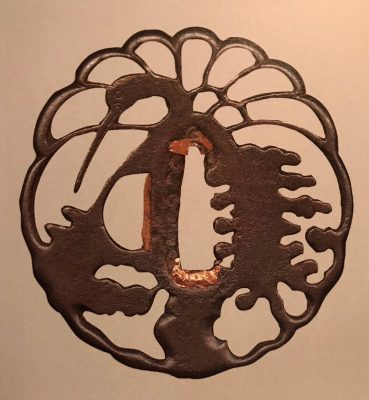

Iron tsuba of almost round form with a brass outlined circular opening (

sukashi) in the bottom adorned with the Myriad Treasures [

takaramono, 宝物] and winter motifs inlaid in cast brass (

suemon-zōgan);

hitsu-ana possibly cut later, both plugged with

shakudo,

nakaga-ana fitted with copper

sekigane. According to Merrily Baird

*) (2001), the symbolism of Myriad Treasures “is associated with the Seven Gods of Good Luck, who carry them in a sack”. Among the treasures, which are said to ensure prosperity, long life, and general good fortunes, are (reading clockwise from the top):

- Sake set [shuki, 酒器], namely flask, ladle, and cups

- Cloves [choji, 丁子]

- Purse of inexhaustible reaches [kinchaku, 巾着]

- Magic mallet [kozuchi, 小槌]

- Key to the storehouse of the Gods [kagi, 鍵]

Then, Pine, Moon, and Bamboo (see below);

- Rhombus, or Lozenge (hosho, 方勝), with the second ideograph meaning victory.

- Sacred (or wish-granting) gem, or jewel [hōju, 宝珠]

- Hats of invisibility [kakuregasa, 隠れ笠]

The Myriad Treasures is carried by the

Seven Gods of Good Luck (a.k.a. the Seven Lucky Gods or Seven Gods of Fortune [

shichifukujin, 七福神], who are transported by the

Treasure Ship [

takarabune, 宝船] during the first three days of the New Year.

Pine, Moon, and Bamboo: bamboo [

take, 竹] and pinecones [

matsukasa, 松笠], or pine [

matsu, 松] – two of the Three Friends of Winter [

shōchikubai, 松竹梅] – symbolize fidelity, fortitude, steadfastness, perseverance, and resilience. The third ‘friend’ – plum, [

ume, 梅] – in this case replaced by the Moon [

tsuki, 月] – large (11 mm) circular opening at 6 o’clock; the three small carved dots represent the dewdrops.

The other side is decorated with an arabesque (

karakusa) of cloves and vines, with carved dots (dewdrops) along the rim.

The overall New Year / Winter connotation of the tsuba is clear. The prominence of the Moon conveys purity, coldness (sadness/loneliness), and slenderness – the inherent qualities of a samurai.

H: 93 mm x W: 90 mm, thickness 4.2 mm at the centre, slightly tapered towards the rim.

*) Merrily Baird. Symbols of Japan: Thematic motifs in art and design. — NY: Rizzoli international publications, 2001.

Seller’s description: École Heianjo - Début Époque EDO (1603 - 1868). Nagamaru gata en fer à décor incrusté en hira-zogan de laiton de tama, choji, jarre à saké et des attributs de Daikoku (maillet, chapeau d'invisibilité et sac de richesse) et de branches de choji de l'autre côté et ajourée en kage-sukashi d'un cercle. H. 9,2 cm