-

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels - circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiseled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or seaweed all over the plate. Hitsu-ana outlined in brass. Four positive silhouette roundels are 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6- pointing crests/flowers; four negative silhouette roundels are bellflower, cherry blossom, and suhama. Yoshirō school (Kaga-Yoshirō). The Momoyama or early Edo period, beginning of 17th century. Size: diameter 77 mm, thickness 3,8 mm

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels - circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiseled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or seaweed all over the plate. Hitsu-ana outlined in brass. Four positive silhouette roundels are 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6- pointing crests/flowers; four negative silhouette roundels are bellflower, cherry blossom, and suhama. Yoshirō school (Kaga-Yoshirō). The Momoyama or early Edo period, beginning of 17th century. Size: diameter 77 mm, thickness 3,8 mm -

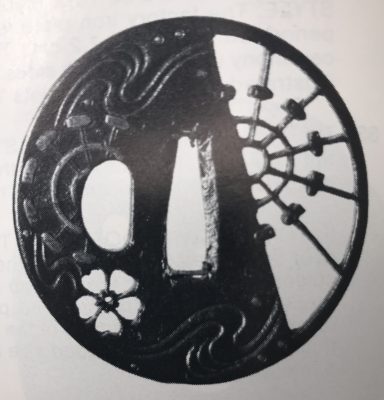

Iron tsuba of almost round form with a brass outlined circular opening (sukashi) in the bottom adorned with the Myriad Treasures [takaramono, 宝物] and winter motifs inlaid in cast brass (suemon-zōgan); hitsu-ana possibly cut later, both plugged with shakudo, nakaga-ana fitted with copper sekigane. According to Merrily Baird*) (2001), the symbolism of Myriad Treasures “is associated with the Seven Gods of Good Luck, who carry them in a sack”. Among the treasures, which are said to ensure prosperity, long life, and general good fortunes, are (reading clockwise from the top):

Iron tsuba of almost round form with a brass outlined circular opening (sukashi) in the bottom adorned with the Myriad Treasures [takaramono, 宝物] and winter motifs inlaid in cast brass (suemon-zōgan); hitsu-ana possibly cut later, both plugged with shakudo, nakaga-ana fitted with copper sekigane. According to Merrily Baird*) (2001), the symbolism of Myriad Treasures “is associated with the Seven Gods of Good Luck, who carry them in a sack”. Among the treasures, which are said to ensure prosperity, long life, and general good fortunes, are (reading clockwise from the top):- Sake set [shuki, 酒器], namely flask, ladle, and cups

- Cloves [choji, 丁子]

- Purse of inexhaustible reaches [kinchaku, 巾着]

- Magic mallet [kozuchi, 小槌]

- Key to the storehouse of the Gods [kagi, 鍵]

- Rhombus, or Lozenge (hosho, 方勝), with the second ideograph meaning victory.

- Sacred (or wish-granting) gem, or jewel [hōju, 宝珠]

- Hats of invisibility [kakuregasa, 隠れ笠]

-

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of mokko form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.4 mm wide. A look-a-like tsub of oval form instead of mokko-gata is illustrated at Robert E. Haynes's Catalog #3,1982 on page 11, lot 15: "Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm" [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. Muromachi (if we follow Robert) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that "waves and rabbit" motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Size: 68.5 x 59.8 x 4.0 mm. NBTHK Certificate № 423120. This tsuba is listed at Yakiba website with the following passage: "Attributions as well as dating of this type of tsuba has been the subject debate over the years. There are those who believe these type of tsuba to be ko-Mino (early Mino School) tsuba, others believe them to be tachi-kanaguchi tsuba. Still others insist they are simply ko-kinko (early soft metal) tsuba. This tsuba was authenticated and determined to be "Ko-Kinko" by the NBTHK". Oval form tsuba with the same design can be found in this collection - TSU-0323.

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of mokko form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.4 mm wide. A look-a-like tsub of oval form instead of mokko-gata is illustrated at Robert E. Haynes's Catalog #3,1982 on page 11, lot 15: "Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm" [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. Muromachi (if we follow Robert) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that "waves and rabbit" motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Size: 68.5 x 59.8 x 4.0 mm. NBTHK Certificate № 423120. This tsuba is listed at Yakiba website with the following passage: "Attributions as well as dating of this type of tsuba has been the subject debate over the years. There are those who believe these type of tsuba to be ko-Mino (early Mino School) tsuba, others believe them to be tachi-kanaguchi tsuba. Still others insist they are simply ko-kinko (early soft metal) tsuba. This tsuba was authenticated and determined to be "Ko-Kinko" by the NBTHK". Oval form tsuba with the same design can be found in this collection - TSU-0323.

TSU-0323. Ko-kinko yamagane tsuba with waves and rabbit motif.

-

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of oval form with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.7 mm wide. Possibly, early Mino (ko-Mino) school. Size: 66.6 x 59.9 x 4.0 mm. Some connoisseurs believe that this kind of tsuba was in mass production at the time. Small animal believed to be a fox, however some attribute it to a long-tailed rabbit or a squirrel. I am leaning towards the rabbit. Similar example is found at Robert E. Haynes Catalog №3, April 9-11, 1982 on page 11, under № 15: “Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm” [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. The only difference betwen my tsuba and his is that his has a square hole on the right shoulder of the seppa-dai. Early Muromachi (if we follow Robert it is even Nanbokucho, 1337-1392) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that “waves and rabbit” motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Mokkōgata tsuba of similar design in this collection - see TSU-0282.

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of oval form with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.7 mm wide. Possibly, early Mino (ko-Mino) school. Size: 66.6 x 59.9 x 4.0 mm. Some connoisseurs believe that this kind of tsuba was in mass production at the time. Small animal believed to be a fox, however some attribute it to a long-tailed rabbit or a squirrel. I am leaning towards the rabbit. Similar example is found at Robert E. Haynes Catalog №3, April 9-11, 1982 on page 11, under № 15: “Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm” [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. The only difference betwen my tsuba and his is that his has a square hole on the right shoulder of the seppa-dai. Early Muromachi (if we follow Robert it is even Nanbokucho, 1337-1392) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that “waves and rabbit” motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Mokkōgata tsuba of similar design in this collection - see TSU-0282.

TSU-0282: Ko-kinko yamagane tsuba with waves and rabbit motif.

-

A very thin kobushi-gata form iron tsuba decorated in openwork (sukashi), some openings filled with grey metal (silver or pewter) treated in a way to resemble cracked ice, ginkgo leaf to recto and plum blossoms to verso in low-relief (takabori) and gold inlay (zōgan), and unevenly folded over rim (hineri-mimi). The overall theme of the piece is linked to the icy ponds, falling ginkgo leaves and blossoming plums in the late winter.

Size: 84 x 80 mm, thickness (center): 2 mm.Signed: Yamashiro no kuni Fushimi no ju Kaneie [Kaneie of Fushimi in Yamashiro Province] [山城國伏見住金家], with Kaō.

Probably the work of Meijin-Shodai Kaneie (c. 1580 – 1600).

The silver or pewter inlays likely a later work that may be attributed to Goto Ichijo (1791 – 1876) or one of his apprentices in the late 19th century, possibly as a tribute to the great Kaneie masters. Here is an article by Steve Waszak dedicated to Kaneie masters and this tsuba in particular.Kaneie

For many tosogu aficionados, this name reigns supreme among all tsubako across Japanese history. The first Kaneie is celebrated for many things. He is recognized as being the first ever to bring pictorial landscape subjects to a canvas so small as that of a tsuba plate. His skill in being able to render classical Chinese landscape themes while working with a material as unyielding as steel, and to do so with the sensitivity he does, is nothing short of astounding. The quality of his workmanship — especially that of his exquisitely carved motif elements and the extraordinary deftness of his tsuchime (槌目 or 鎚目, hammer-blow) utilizing such thin plates — astonishes even to this day. His sensibilities concerning the shaping of his sword guards and the presentation of the rims were no less innovative than his subject matter. He was among the very first to regularly sign his name as a tsuba smith. And it is likely that he served the great warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the latter years of the 16th century. Despite the great fame and reputation of Kaneie, very little of the lives of the two men who are seen by most scholars as the “true Kaneie” tsubako of the Momoyama and earliest Edo Periods is known to us now. They were both smiths working in steel, with occasional added soft-metal inlay (usually serving to highlight features), and both made sword guards of the same style, using subject matter focused on landscapes, allusions to historical events, or religious themes. The first of these men is often referred to as “O-Shodai,” or Great First Generation, while the second is known as “Meijin-Shodai,” or Famous First Generation. While some see subsequent generations stemming from these first two men, others have the O-Shodai and the Meijin-Shodai as THE two true Kaneie and make a sharp distinction between these two smiths and any others who may share the name.The work of the O-Shodai may appear with two different mei. One of these is written “Joshu Fushimi Ju Kaneie,” while his work may also carry a mei reading “Yamashiro no Kuni Fushimi Ju Kaneie.” It is thought by some scholars that the earlier works present with the “Joshu” mei, while his later works feature the “Yamashiro” mei. However, there are only some five or six tsuba extant with the “Joshu” signature, so we should not necessarily see works with the “Yamashiro” signature as dating only to the latest years of his working life. The answers to the questions of exactly when Kaneie might have begun his life as a tsubako, or how old he was when he moved to sign his works with the “Yamashiro” mei, will probably remain shrouded in uncertainty.The association between Kaneie and Toyotomi Hideyoshi is speculative, to be sure, but the circumstantial evidence is tantalizing. The area of Fushimi is thought to have been an entirely unremarkable land prior to Hideyoshi’s building of a castle there, so it would seem unlikely that the first Kaneie would have been working in such a nondescript place, much less including the place name in his mei, before Hideyoshi’s putting it on the map, so to speak. Why emphasize such pride of place in one’s signature unless the place itself carries a certain weight? The name “Kaneie” translates roughly to “gold family,” which, given Hideyoshi’s notorious love of gold, would seem too much of a coincidence when combined with the explicit mention of Fushimi in the signatures. Combine this with the consideration of what is an equally compelling relationship between the celebrated tsubako Nobuie and Oda Nobunaga (“Nobuie” means roughly “of the family of “Nobu”), whom Hideyoshi served as a top general until Oda’s demise in 1582, and the circumstantial evidence becomes even harder to deny the plausibility of. Oda, ever the innovator, may have been the one responsible for birthing the practice of tsubako regularly signing their works. Having a superb smith like Nobuie affix the name to the tsuba as a regular practice establishes a sort of “brand name,” a brand coming with the seal of approval of Oda Nobunaga. It is more than possible that Nobunaga may have then used these valuable sword guards as rewards given to vassals and other important relations to honour them for their services to him, a practice that would have allowed Nobunaga to avoid having to use gold, guns, swords, horses, or land to do so. The awarding of a magnificent Nobuie tsuba to a deserving warrior, an appreciated ally, or a family member would bring honour to the recipient, of course, but would also honour the maker of the sword guard, and even the giver of the object. Such a way of thinking would be absolutely typical of him, and given that both Oda Nobunaga and Nobuie were men of Kiyosu in Owari in the early Momoyama Period, it does not strain credulity to imagine that the above dynamic could have occurred in just this way. If indeed it did, Toyotomi Hideyoshi is unlikely to have let this pass unnoticed. He may even have been so honoured himself! When he rose to power very shortly after Oda’s death, then, and when he reinforced and consolidated that power in the late 1580s and early 1590s, which included the building of the castle at Fushimi, perhaps he sought to emulate the Oda vision and practice of establishing a “royal tsubako.” If so, Kaneie would have been that smith.As noted, this scenario is speculative, and not a little romantic. This does not mean, however, that it is in fact not likely, for there would be a number of coincidences involved for it to be entirely false.Tsuba scholars will say that Kaneie’s skills in the making of his sword guards indicate an armour-making background. This is an interesting viewpoint, but one can’t help but wonder how many armourers were possessed of such fluent literacy in lyrical Chinese historical tales that they could then represent them as motifs on steel plates. Kaneie subjects often are in the form of Chinese landscapes and allusions, as noted, one of which — The Eight Views of the Xiao and the Xiang — was very well known as a famous subject of Chinese painting and poetry from the Song Dynasty. There exist Kaneie tsuba which depicts at least some of these “views,” and it seems unlikely that if one or more of them were to be created, not all of them would be, in a sort of “series.” The cultural and literary fluency Kaneie would seem to have had, then, may suggest a Buddhist background, and indeed, some of the subjects seen are explicitly Buddhist in nature. Perhaps his background then, somehow offering a dovetailing of metalwork and Buddhist teachings; in any event, we are all the richer for at least some of the works of Kaneie to have survived to reach us today.One of the hallmarks of Kaneie tsuba (real ones) is the extreme thinness of the plate, combined with utterly superb tsuchime expression of that plate. To be able to hammer the plate to achieve such strength of expression while the plate is so thin is seen by the Japanese as practically miraculous. A notable and important kantei point between the early masterpieces by the two “Shodai” Kaneie and the tsuba made by followers is this thinness of the plate. Another kantei point: because the plate is so thin when raised areas representing motif elements are present, they are inlaid into the plate, because trying to carve them from such a thin plate would be practically impossible: the likelihood of piercing the plate would be high, and the plate in that area, even if not pierced, would be significantly weakened by trying to manage the raising of a motif element from the plate. In real Kaneie works, then, one would expect any raised motif elements to be inlaid.Other highlights: the “Shodai” Kaneie are famous for the kobushi-gata (拳形) or “fist-shaped” design in their work, but despite this, there actually aren’t that many extant sword guards boasting this shape. Another feature for which the Kaneie are justly famous is their folding over of the lip of the rim onto the plate in a very tasteful manner, just here and there, rather than uniformly across the tsuba. However, again, this feature is actually not commonly seen, either. The combination, then, of a kobushi-gata shape with the rim folded over in just a few areas is that much rarer.Which brings us to the featured piece.Here is a Kaneie tsuba, a “Meijin-Shodai” Kaneie, which presents with a very thin plate, being between 1.5 and 2mm in thickness. The motif elements are inlaid, as we should expect. The sugata (姿, shape) is Kobushi-gata with the rim folded over in only a few places, representing a relatively infrequently encountered form, as stated. The tsuba here is fortunate not to have any added hitsu-ana, unlike many or most other Kaneie do. The sukashi elements are fascinating to consider, being difficult to determine the meaning of; however, the raised elements clearly point to a seasonal motif, with cherry and plum blossoms on the omote for Spring, and ginkgo on the ura for Fall. The inlaid metal in two of the openings — silver, shibuichi, or pewter, perhaps — is very likely a later addition, probably 19th-century, and more specifically, late-19th-century. The finishing on these inlaid portions has all the hallmarks of Goto Ichijo workmanship. Namely, the treatment of the surface of the inlay to resemble fallen snow (in the Japanese sense of things) is expressed in a very Ichijo sense of things, and, given the great importance of Kaneie tsuba, and the seasonal expression the motif of the guard has, it is plausible that the inlay is Ichijo work or that of one of his top students. In any event, this inlay complements the rest of the tsuba beautifully. The inlay also resembles the art of kintsugi (金継ぎ, golden joinery) or the Japanese practice of ceramic repair using lacquer when a piece is particularly special or important. In this way, a nod is given to Tea Culture, too, creating a wonderful blending of associations and allusions, typical of the highest Japanese aesthetic sense.At 8.4cm, the tsuba is of an excellent size and is in great condition (no rust, no deep rust pitting, no fire damage). There is, intriguingly, one small sign of battle damage at 6:00 on the guard: it would seem a sword blow cut into the tsuba at the rim, and penetrated slightly into the plate. The superb repair represented by a little stitch or two right at the rim and along a few millimetres of the plate is visible on very close inspection. The repair is old, probably nearly contemporary with when the tsuba was made. Given the high status of Kaneie in their lifetime (as tsubako for Hideyoshi, one might imagine their importance), and given the obvious high quality of this piece, it is not surprising that the finest repair efforts were put into its care.The name Kaneie justly enjoys its fame and accolades as pre-eminent among the tens of thousands of tsubako in Japanese history. We are fortunate indeed to have had a small number of the works of the early masters survive to this day. The first of their kind, and as most scholars and aficionados would wholeheartedly agree, the best of their kind, Kaneie sword guards remain among the very finest examples of the Japanese metal-working traditions. -

The chrysanthemoid (kiku-gata) iron plate with polished surface decorated with arabesque (karakusa) and paulownia (kiri) leaves and flowers in brass, copper and silver flush inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Some of the inlay goes over the edge. Kozuka- and kogai-hitsu-ana are filled with lead plugs. Sekigane of copper. Chrysanthemum and paulownia are the symbols of imperial family. The face is signed: Izumi no Kami to the right of nakago-ana, and Yoshiro on the left; the back is signed Koike Naomasa. His signed work is considered by many experts to have been made-to-order only. The original wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) signed by Dr. Kazutaro Torigoye and dated Showa 39 (1964). The late Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: 89 mm x 84 mm x 3.6 mm; Weight: 170 g. Hakogaki lid: Yoshirō kikka-gata Hakogaki lid inside: Iron, signed on the omote: Izumi no Kami – Yoshirō; on the ura: Koike Naomasa. Kikka-gata, pronounced maru-mumi, two hitsu-ana, karakusa, and kiri design in brass, silver, and suaka hira-zōgan. Height 8.5 cm, thickness 3.5 mm. Herewith I judge this work as authentic. On a lucky day in July of 1964. Torigoe Kōdō [Kazutarō] + kaō According to Robert Haynes [Catalog #7, 1983; №32, page 42-43] "This full form of the signature is seen very rarely". His example, illustrated in that catalogue, measures: height = 86 mm, thickness at seppa-dai = 3.75 mm and signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back and Koike Naomasa on the face. The further description of his specimen by Robert Haynes:

The chrysanthemoid (kiku-gata) iron plate with polished surface decorated with arabesque (karakusa) and paulownia (kiri) leaves and flowers in brass, copper and silver flush inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Some of the inlay goes over the edge. Kozuka- and kogai-hitsu-ana are filled with lead plugs. Sekigane of copper. Chrysanthemum and paulownia are the symbols of imperial family. The face is signed: Izumi no Kami to the right of nakago-ana, and Yoshiro on the left; the back is signed Koike Naomasa. His signed work is considered by many experts to have been made-to-order only. The original wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) signed by Dr. Kazutaro Torigoye and dated Showa 39 (1964). The late Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: 89 mm x 84 mm x 3.6 mm; Weight: 170 g. Hakogaki lid: Yoshirō kikka-gata Hakogaki lid inside: Iron, signed on the omote: Izumi no Kami – Yoshirō; on the ura: Koike Naomasa. Kikka-gata, pronounced maru-mumi, two hitsu-ana, karakusa, and kiri design in brass, silver, and suaka hira-zōgan. Height 8.5 cm, thickness 3.5 mm. Herewith I judge this work as authentic. On a lucky day in July of 1964. Torigoe Kōdō [Kazutarō] + kaō According to Robert Haynes [Catalog #7, 1983; №32, page 42-43] "This full form of the signature is seen very rarely". His example, illustrated in that catalogue, measures: height = 86 mm, thickness at seppa-dai = 3.75 mm and signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back and Koike Naomasa on the face. The further description of his specimen by Robert Haynes:"Early signed example of the work of Koike Naomasa. The kiku shape iron plate is well finished. The flush inlay is brass, for the scroll work on both sides, with the leaves and kiri mon in brass, copper and silver with strong detail carving. Some of the inlay goes almost over the edge, which is goishi gata. The large hitsuana are plugged in lead with starburst kokuin surface design. [...]The face is signed in deep bold kanji: Koike Naomasa; the back is signed: Izumi no Kami, on the right and Yoshiro on the left. There are one or two small pieces of inlay missing. Sold by Sotheby London, Oct. 27, 1981, lot 368. Height = 86 mm, thickness (seppa-dai) = 3.75 mm, (edge) = 4 mm."

Another similar example presented at: "Tsuba" by Günter Heckmann, 1995, №T55 — "Designation: Koike Naomasa. Mid Edo, end of the 17th century. Iron, hira-zogan in brass, copper, silver and shakudo, katakiri-bori. Tendrils and leaves. 87.0 x 78.0 x 4.0 mm." Reference: Japanische Schwertzierate by Lumir Jisl, 1967, page. 13. [SV: Actually, his tsuba is signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back; and Koike Naomasa on the front, exactly as Robert Haynes's tsuba. Dating this tsuba Mid-Edo, 17th century may be considered a misattribution]. More details regarding the Yoshirō tsuba. -

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels – circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiselled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or leaves all over the plate. Both hitsu-ana are trimmed with brass. Nakago-ana of trapezoidal form. A distinctive character of this tsuba is a mon at 12 hours, depicting paulownia, or Kiri-mon [桐紋] – a symbol of the Toyotomi clan, led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣 秀吉, 1537 – 1598). Kiri-mon was also used as fuku-mon (alternative family crests) for the Imperial Family and Imperial Court. Another important emblem at 6 o’clock is the Katakura clan [片倉氏, Katakura-shi] family crest. Katakura Kagetsuna (片倉 景綱, 1557 – 1615), a retainer of Date Masamune (伊達 政宗, 1567 – 1636); Kagetsuna was operational in Hideyoshi’s Odawara campaign in 1590, which ultimately ended the unification of Japan. Unsigned but may be attributed to Koike Yoshirō Naomasa or his workshop (Yoshirō, orKaga-Yoshirō school). Dimensions: Diameter: 85.5 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 5.0 mm.

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels – circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiselled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or leaves all over the plate. Both hitsu-ana are trimmed with brass. Nakago-ana of trapezoidal form. A distinctive character of this tsuba is a mon at 12 hours, depicting paulownia, or Kiri-mon [桐紋] – a symbol of the Toyotomi clan, led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣 秀吉, 1537 – 1598). Kiri-mon was also used as fuku-mon (alternative family crests) for the Imperial Family and Imperial Court. Another important emblem at 6 o’clock is the Katakura clan [片倉氏, Katakura-shi] family crest. Katakura Kagetsuna (片倉 景綱, 1557 – 1615), a retainer of Date Masamune (伊達 政宗, 1567 – 1636); Kagetsuna was operational in Hideyoshi’s Odawara campaign in 1590, which ultimately ended the unification of Japan. Unsigned but may be attributed to Koike Yoshirō Naomasa or his workshop (Yoshirō, orKaga-Yoshirō school). Dimensions: Diameter: 85.5 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 5.0 mm.

Kiri-mon

Katakura-mon

-

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of sea waves in low relief carving (kebori) and pierced with design of cherry blossom in negative silhouette (in-sukashi) and water wheel in positive silhouette (ji-sukashi). The solid portion of the plate has a shallow groove just before the edge. Copper sekigane. School attribution is unclear. Unsigned. Momoyama period, 16th - 17th century. Dimensions: Height: 70.3 mm, width: 71.1 mm, thickness at seppa-dai: 4.4 mm, at rim 4.1 mm. Provenance: Robert E. Haynes, Mark Weisman. This is what shibuiswords.com says about this tsuba:

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of sea waves in low relief carving (kebori) and pierced with design of cherry blossom in negative silhouette (in-sukashi) and water wheel in positive silhouette (ji-sukashi). The solid portion of the plate has a shallow groove just before the edge. Copper sekigane. School attribution is unclear. Unsigned. Momoyama period, 16th - 17th century. Dimensions: Height: 70.3 mm, width: 71.1 mm, thickness at seppa-dai: 4.4 mm, at rim 4.1 mm. Provenance: Robert E. Haynes, Mark Weisman. This is what shibuiswords.com says about this tsuba:"A very unusual iron plate tsuba. The solid plate is carved with waves on both sides. A cherry bloom in sukashi, lower left, and the right third of the plate in openwork with design of a water wheel. The rim with some iron bones. The hitsu-ana is original but the shape may have been slightly changed. One would expect this to be the work of the early Edo period, but the age of the walls of the sukashi would suggest that this is a work of the middle Muromachi period. This must be the forerunner for the Edo examples we see of this type of design." (Haynes)

I managed to find a look-a-like tsuba in Haynes Catalog #5, 1983, pp. 20-21, №44: "Typical later Heianjo brass inlay example. Ca. 1725. Ht. 7 cm., Th. 4.5 mm., $100/200".We see that the plate design of both tsuba is the same, and the only difference is the trim. It would be logical to assume that both pieces were made at about the same time, rather than 225 years apart. To be fair, let's accept that they were made in Momoyama period.

Haynes Catalog #5, 1983, pp. 20-21, №44.

-

Iron tsuba of slightly elongated round form decorated with design of melon flowers, vines, and leaves in brass flat inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Slightly raised rim (mimi) carved in a way to simulate ring-shaped covering (fukurin). Kozuka hitsu-ana and kogai hitsu-ana both plugged with soft metal (tim or lead). Copper sekigane. Heianjō or Kaga School. Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Iron, hira-zōgan brass inlay. Round (maru gata) form, diameter 79 mm. Size: 80.3 x 78.4 mm; thickness at seppa-dai: 3.4 mm; at the middle: 3.8 mm; before the rim: 2.4 mm, rim: 2.8 mm. Note on design: though this design resembles family crests with oak and mulberry leaves, I believe it's a melon flower [see Jeanne Allen. Designer's guide to Samurai Patterns. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1990, page 114, №130 "Melon Flowers":Note about the distribution of thickness (niku-oki): "this tsuba has toroid features, niku raises from the rim towards the centre but thins once more out when approaching the seppa-dai" [M. Sesko, "Handbook...", p. 48].

Iron tsuba of slightly elongated round form decorated with design of melon flowers, vines, and leaves in brass flat inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Slightly raised rim (mimi) carved in a way to simulate ring-shaped covering (fukurin). Kozuka hitsu-ana and kogai hitsu-ana both plugged with soft metal (tim or lead). Copper sekigane. Heianjō or Kaga School. Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Iron, hira-zōgan brass inlay. Round (maru gata) form, diameter 79 mm. Size: 80.3 x 78.4 mm; thickness at seppa-dai: 3.4 mm; at the middle: 3.8 mm; before the rim: 2.4 mm, rim: 2.8 mm. Note on design: though this design resembles family crests with oak and mulberry leaves, I believe it's a melon flower [see Jeanne Allen. Designer's guide to Samurai Patterns. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1990, page 114, №130 "Melon Flowers":Note about the distribution of thickness (niku-oki): "this tsuba has toroid features, niku raises from the rim towards the centre but thins once more out when approaching the seppa-dai" [M. Sesko, "Handbook...", p. 48].

Jeanne Allen. Designer's guide to Samurai Patterns. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1990. Page 114, №130.

-

Iron tsuba in a form of an eight-petalled blossom (lotus) form, petals separated by linear low-relief carving, both hitsu-ana filled with gold plugs, the surface decorated with tsuchime-ji, rich grey-brownish patina, niku from 4 mm in the centre to 6 mm at the rim. Strong (futoji-mei) Nobuie [信家] signature to the left of nakago-ana. Attributed to the 2nd generation of Nobuie masters (Nidai Nobuie).

Size: outer diameter 84 mm, thickness at centre: 4 mm, at rim: 6 mm. Wight: 167 g.Signed: Nobuie [信家]

Probably the work of Nidai Nobuie (c. 1600).

The gold plugs are likely a later work.