-

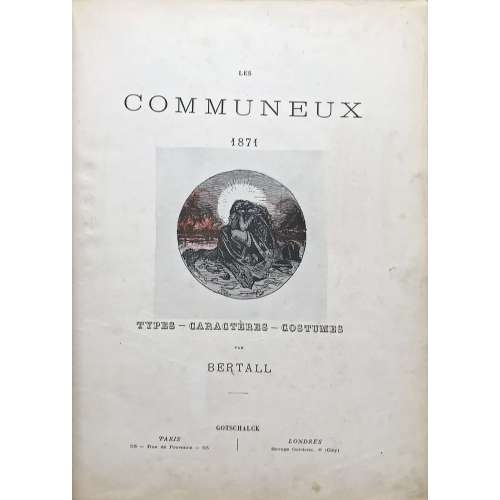

Folio (240 x 320 mm), hardbound in blue-aubergine cloth with gilt lettering and decoration. Album with Avant-Propos and 34 hand-colored lithographs by Bertall, numbered 1 through 34. Details in Russian: "Памяти парижской коммуны".

Folio (240 x 320 mm), hardbound in blue-aubergine cloth with gilt lettering and decoration. Album with Avant-Propos and 34 hand-colored lithographs by Bertall, numbered 1 through 34. Details in Russian: "Памяти парижской коммуны". -

Iron tsuba of round form with brown patina decorated with the design of a Buddhist temple bell (tsurigane) in openwork (sukashi), with details outlined in brass wire (sen-zōgan), the outer ring decorated with two rows of brass dots (ten-zōgan), and the bell details carved in sukidashi-bori as on kamakura-bori pieces.

Ōnin school. Unsigned. Late Muromachi period, 16th century. Dimensions: 88.8 x 88.3 x 3.0 mm. As per Merrily Baird, two legends are usually associated with the image of tsurigane, a large, suspended Buddhist bell: one is that of Dojo Temple (Dojo-ji), and the other is of Benkei stealing the tsurigane of Miidera Temple. Interestingly, this type of bell (tsurigane) is not described as a family crest (mon), while suzu and hansho bells are. -

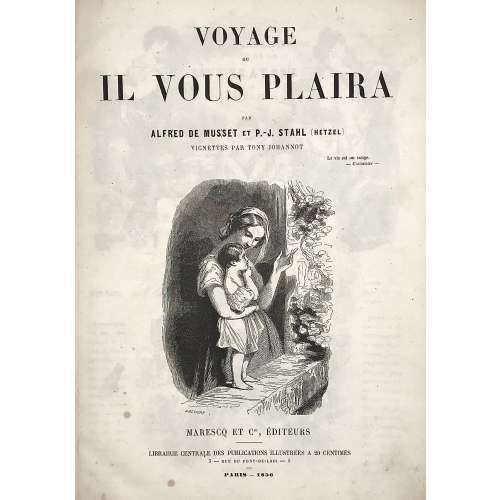

Voyage ou Il vous plaira by Alfred de Musset and P.-J. Stahl (Hetzel); Tony Johannot (illustrations). [Les chefs d'oeuvres de la litterature et de l'illustration] // Marescq et Cie, éditeurs, - Paris, 1856.

Contes de Charles Nodier by Jean Charles Emmanuel Nodier (1780 – 1844) illustrated by H. Émy.

Owner's binding in red half Morocco, A4 (297 x 219 mm). "Voyage ou Il vous plaira" (60 pages) and fairy tales by Charles Nodier with illustrations by H. Émy (Armand-Louis-Henri Telory, born in Strasbourg in 1820 and died in 1874): "La Fée aux miettes" ; "Le songe d'or (fable levantine)"; "La légende de la Soeur Béatrix"; "Trilby"; Inès de las Sierras"; "Baptiste Montauban"; "Smarra ou les démons de la nuit"; "La neuvaine de la Chandeleur"; "La combe de l’homme mort". Extensive foxing, owner's pencil drawings on some pages, otherwise good condition.

-

Le Petit Chaperon rouge (Little Red Riding Hood), three wood engravings by Gustave Doré, 1864: "En passant dans un bois elle rencontra compère le Loup"; "Le Chaperon rouge fut bien étonné de voir comment sa grand'mère était faite en son déshabillé"; "Cela n'empêche pas qu'avec ses gran dents il avait mangé une bonne grand'mère". Engraved by Adolphe Pannemaker. Le Petit Poucet (Little Thumb), one wood engraving by Gustave Doré, 1864: "Une bonne femme vint leur ouvrir". Engraved by Héliodore-Joseph Pisan. La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), one wood engraving by Gustave Doré, 1864: "Il marcha vers le château qu'il voyait au bout d'une grande avenue où il entra". Engraved by Héliodore-Joseph Pisan. Medium: Paper; Wood engraving. Illustrations for P.-J. Hetzel's edition of Perrault's Fairy Tales (Les Contes de Perrault) by Gustave Doré published in 1864. Size: frame: 428 x 302 mm; sheet: 280 x 231 mm; image: 194 x 244 mm.

Le Petit Chaperon rouge (Little Red Riding Hood), three wood engravings by Gustave Doré, 1864: "En passant dans un bois elle rencontra compère le Loup"; "Le Chaperon rouge fut bien étonné de voir comment sa grand'mère était faite en son déshabillé"; "Cela n'empêche pas qu'avec ses gran dents il avait mangé une bonne grand'mère". Engraved by Adolphe Pannemaker. Le Petit Poucet (Little Thumb), one wood engraving by Gustave Doré, 1864: "Une bonne femme vint leur ouvrir". Engraved by Héliodore-Joseph Pisan. La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), one wood engraving by Gustave Doré, 1864: "Il marcha vers le château qu'il voyait au bout d'une grande avenue où il entra". Engraved by Héliodore-Joseph Pisan. Medium: Paper; Wood engraving. Illustrations for P.-J. Hetzel's edition of Perrault's Fairy Tales (Les Contes de Perrault) by Gustave Doré published in 1864. Size: frame: 428 x 302 mm; sheet: 280 x 231 mm; image: 194 x 244 mm. -

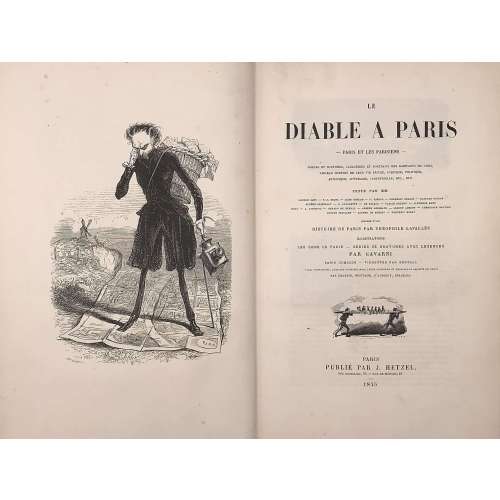

A two-volume set, published in Paris by P.-J. Hetzel in 1845 and 1846.

Vol. 1:

Title: LE | DIABLE A PARIS | — PARIS ET LES PARISIENS — | MŒURS ET COUTUMES, CARACTERES ET PORTRAITS DES HABITANTS DE PARIS, | TABLEAU COMPLET DE LEUR VIE PRIVEE, PUBLIQUE, POLITIQUE, | ARTISTIQUE, LITTERAIRE, INDUSTRIELLE, ETC., ETC. | TEXTE PAR MM. | GEORGE SAND — P.-J. STAHL — LEON GOZLAN — P. PASCAL — FREDERIC SOULIE — CHARLES NODIER | EUGENE BRIFFAULT — S. LAVALETTE — DE BALZAC — TAXILE DELORD — ALPHONSE KARR | MÉRY — A. JUNCETIS — GERARD DE NERVAL — ARSÈNE HOUSSAYE — ALBERT AUBERT — THÉOPHILE GAUTIER | OCTAVE FEUILLET — ALFRED DE MUSSET — FRÉDÉRIC BÉRAT | précédé d’une | HISTOIRE DE PARIS PAR THEOPHILE LAVALLÉE | ILLUSTRATIONS | LES GENS DE PARIS — SERIES DE GRAVURES AVEC LEGENDES | PAR GAVARNI | PARIS COMIQUE — VIGNETTES DE BERTALL | VUES, MONUMENTS, EDIFICES PARTICULIERS, LIEUX CÉLÈBRES ET PRINCIPAUX ASPECTS DE PARIS | PAR CHAMPIN, BERTRAND, D’AUBIGNY, FRANÇAIS. | [DEVICE] | PARIS | PUBLIÉ PAR J. HETZEL, | RUE RICHELIEU, 76 – RUE DE MÉNARS, 10. | 1845 ||

Pagination: ffl, [2 – h.t. / Paris: Typographie Lacrampe et Comp., Rue Damiette, 2 ; Papeir de la fabrique de sainte-marie] [2 – blank / frontis. ‘Diable’ with lantern standing on map of Paris] [2 – t.p. /blank] [I] II-XXXII, [1] 2-380, bfl. Sheet size: 27.5 x 17.5 cm.

Collation: 4to; A(4) – D(4), [1(4)] 2(4) – 47(4), 48(2); illustrations: frontispiece, vignette title-page, numerous text engravings and 99 plates.

Vol. 2: Title: LE | DIABLE A PARIS | — PARIS ET LES PARISIENS — | MŒURS ET COUTUMES, CARACTERES ET PORTRAITS DES HABITANTS DE PARIS, | TABLEAU COMPLET DE LEUR VIE PRIVEE, PUBLIQUE, POLITIQUE, | ARTISTIQUE, LITTERAIRE, INDUSTRIELLE, ETC., ETC. | TEXTE PAR MM. | DE BALZAC — EUGÈNE SUE — GEORGE SAND — P.-J. STAHL — ALPHONSE KARR | HENRY MONNIER — OCTAVE FEUILLET — DE STENDAHL — LEON GOZLAN — S. LAVALETTE — ARMAND MARRAST | LAURENT-JAN —ÉDOUARD OURLIAC — CHARLES DE BOIGNE — ALTAROCHE — EUG. GUINOT | JULES JANIN — EUGENE BRIFFAULT — AUGUSTE BARBIER — MERQUIS DE VARENNES — ALFRED DE MUSSET | CHARLES NODIER — FRÉDÉRIC BÉRAT — A. LEGOYT| précédé d’une | GÉOGRAPHIE DE PARIS PAR THEOPHILE LAVALLÉE | ILLUSTRATIONS | LES GENS DE PARIS — SERIES DE GRAVURES AVEC LEGENDES | PAR GAVARNI | PARIS COMIQUE — PANTHÉON DU DIABLE A PARIS PAR BERTALL | VUES, MONUMENTS, EDIFICES PARTICULIERS, LIEUX CÉLÈBRES ET PRINCIPAUX ASPECTS DE PARIS | PAR CHAMPIN, BERTRAND, D’AUBIGNY, FRANÇAIS. | [DEVICE] | PARIS | PUBLIÉ PAR J. HETZEL, | RUE RICHELIEU, 76 – RUE DE MÉNARS, 10. | 1846 || Pp. : ffl, [2 – h.t. / Paris: Typographie Lacrampe et Comp., Rue Damiette, 2 ; Papeir de la fabrique de sainte-marie] [2 – t.p. /blank] [I] II-LXXX, [1] 2-364, bfl. Sheet size: 27.5 x 17.5 cm. Collation: 4to; A(4) – I(4) – J(4), 1(4), 2(4) – 45(4), 46(2); illustrations: vignette title-page, numerous text engravings and 112 plates.Binding: [allegedly Roger de Coverly (British, 1831 — 1914)], 28.2 x 19 cm, ¾ brown calf ruled in gilt, brown marbled boards, nonpareil marbled endpapers, raised and ruled in gilt bands, floral devices and title lettering to spine. AEG. Foxing to flyleaves, tips of corners just a very little rubbed as are the glazed marbled paper boards; endpapers foxed; very occasional light scattered foxing of text.

Provenance: (1) Armorial bookplate (Ex Libris Sir John Whittaker Ellis, 1st Baronet (1829 – 1912), Lord Mayor of London 1881; (2) Bookplate Ex Libris Robert Frederick Green) dated 1909.

Reference: L. Carteret (1927) pp. 203-207: the first edition, lacking the publisher's white pictorial wrappers. -

Iron tsuba of mokkō form decorated with inome (wild boar's eye) in openwork (sukashi) outlined with brass wire. The plate decorated with 3 concentric circular rows of brass dots in ten-zōgan. Center of the plate outlined with the inlaid circular brass wire (sen-zōgan). Some dots and the outline of inome on the face are missing.

Ōnin school. Unsigned. Mid Muromachi period, middle of the 15th century. Dimensions: 72.1 x 71.3 x 2.3 mm. -

Thin iron plate of round form and black color carved in sukidashi-bori with design of rocks, waves, clouds, temple gates (torii), mountain pavilion and 5-storey pagoda on both sides, alluding to Todai-ji temple in Nara. Hitsu-ana pierced later. Very narrow very slightly raised rim. Copper sekigane.

Late Muromachi period, 16th century. Dimensions: 88.7 x 88.0 x 2.4 mm (seppa-dai), 1.8 mm (base plate).Reference: “Art of the Samurai” on page 232, №140: ”Kamakura tsuba with Sangatsu-do tower and bridge. Muromachi period, 16th century. 83 mm x 80 mm. Unsigned. Tokyo National Museum. The mountain pavilion and bridge carved in sunken relief on the iron tsuba – both part of Tōdai-ji, a temple in Nara – are detailed in fine kebori (line) engraving. As a result of the chiseling used to create the relief, the ground of the piece is relatively thin".

-

Thin six-lobed iron plate of brownish color is carved on each side with a groove that follows the rim and a concentric grooves around the center of the plate, also carved with six thin scroll lines (mokkō or handles, kan) that follow the shape of the rim. Mokume surface treatment. Hitsu-ana possibly added at a later date, and kogai-hitsu-ana plugged with gold. Silver sekigane.

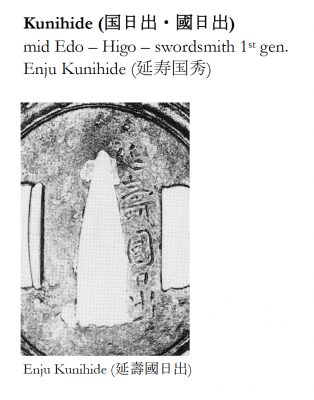

Signed: Kunihide [國秀]. Higo school, 1st generation swordsmith.

Mid Edo period, ca. 1800.

Would be possibly attributed to Kamakura-bori school revival of the 19th century.

References: Nihon Tō Kōza, Volume VI / Japanese Sword / Kodōgu Part 1, page 231: Enju Kunihide, a tōshō from Higo: "...forging of the jigane is excellent, and there are also pieces with mokume hada."

Haynes Index Vol. 1, p. 741, H 03569.0: "Enju Kunihide in Higo province, died 1830, student of Suishinshi Masahide. Retainer of the Hosokawa Daimyō, etc."

Additional Information from Markus Sesko: This tsuba indeed is made by Enju Kunihide, who in his later years signed the HIDE [秀] character as HI [日] and DE [出], as here: Size: 77.4 x 74.9 x 2.7 mm

Similar pieces are:

1. In this collection № TSU-0341: Kamakura-bori tsuba with mokkō motif. Muromachi period, 15th - 16th century.

2. Dr. Walter A. Compton Collection, 1992, Christie’s auction, Part II, pp. 14-15, №16: “A kamakurabori type tsuba, Muromachi period, circa 1400. The thin, six-lobed iron plate is carved on each side with a wide groove that follows the shape of the rim, and with six scroll lines and a single thin circular groove. […] The hitsu-ana was added at a later date, circa 1500-1550. Height 8.3 cm, width 8.6 cm, thickness 2.5 mm. The tsuba was initially intended to be mounted on a tachi of the battle type in use from Nambokucho to early Muromachi period (1333-1400)”. Sold at $935.

Size: 77.4 x 74.9 x 2.7 mm

Similar pieces are:

1. In this collection № TSU-0341: Kamakura-bori tsuba with mokkō motif. Muromachi period, 15th - 16th century.

2. Dr. Walter A. Compton Collection, 1992, Christie’s auction, Part II, pp. 14-15, №16: “A kamakurabori type tsuba, Muromachi period, circa 1400. The thin, six-lobed iron plate is carved on each side with a wide groove that follows the shape of the rim, and with six scroll lines and a single thin circular groove. […] The hitsu-ana was added at a later date, circa 1500-1550. Height 8.3 cm, width 8.6 cm, thickness 2.5 mm. The tsuba was initially intended to be mounted on a tachi of the battle type in use from Nambokucho to early Muromachi period (1333-1400)”. Sold at $935.

3. And another one in Robert E. Haynes Catalog #9 on page 24-25 under №23: “Typical later Kamakura-bori style work. This type of plate and carving show the uniform work produced by several schools in the Muromachi </em period. Some had brass inlay and others were just carved as this one is. The hitsu are later. Ca. 1550. Ht. 8.8 cm, Th. 3.25 mm”. Sold for $175.

3. And another one in Robert E. Haynes Catalog #9 on page 24-25 under №23: “Typical later Kamakura-bori style work. This type of plate and carving show the uniform work produced by several schools in the Muromachi </em period. Some had brass inlay and others were just carved as this one is. The hitsu are later. Ca. 1550. Ht. 8.8 cm, Th. 3.25 mm”. Sold for $175.

-

Iron tsuba of mokkō form (mokkōgata) pierced (sukashi) and inlaid with precast dark brass inlay (taka-zōgan) with somewhat abstract/geometrical design that can be liberally described as pines, mist, and snow.

Momoyama or early Edo period. End of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century. Heianjō school. Unsigned. Dimensions: 86.8 x 82.9 x 4.5 mm. -

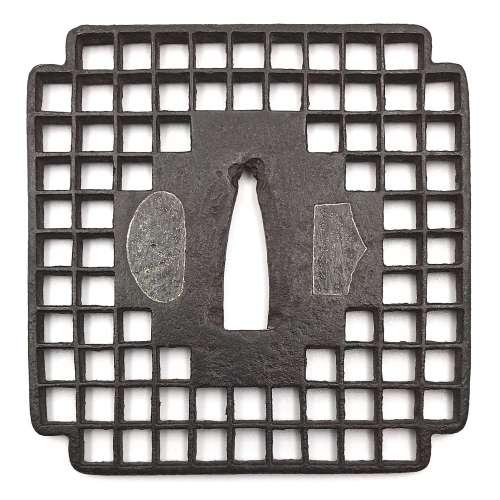

Iron tsuba of square with cut-off edges form (sumi-iri-kakugata) with lattice design in openwork (sukashi) and pierced center.

Unsigned. Late Muromachi period, ca. 16th century.

Size: 73.2 x 72.4 x 3.6 mm References: 1) Tsuba Kanshoki. Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975, p. 95, lower image. It's also called Kyō shōami. 2) KTK-11: Koshi motif, Late Muromachi (16th c.) -

Iron tsuba of square with cut-off edges form (sumi-iri-kakugata) with lattice design in openwork (sukashi) and solid center. Hitsu-ana plugged with lead.

Unsigned. Late Muromachi period, ca. 16th century.

Size: 81.3 x 80.0 x 3.6 mm References: 1) Tsuba Kanshoki. Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975, p. 95, lower image. It's also called Kyō shōami. 2) KTK-11: Koshi motif, Late Muromachi (16th c.) -

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels – circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiselled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or leaves all over the plate. Both hitsu-ana trimmed with brass. Nakago-ana of trapezoidal form. A distinctive character of this tsuba is a mon at 6 hours depicting tomoe (comma). Yoshirō school (Kaga-Yoshirō). Attributed to Koike Yoshirō Naomasa himself. Unsigned. The Momoyama or early Edo period, end of the 16th to the first half of the 17th century (1574-1650). Size: Diameter 82.0 mm, thickness 3.8 mm at seppa-dai, 3.4 mm at rim.

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels – circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiselled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or leaves all over the plate. Both hitsu-ana trimmed with brass. Nakago-ana of trapezoidal form. A distinctive character of this tsuba is a mon at 6 hours depicting tomoe (comma). Yoshirō school (Kaga-Yoshirō). Attributed to Koike Yoshirō Naomasa himself. Unsigned. The Momoyama or early Edo period, end of the 16th to the first half of the 17th century (1574-1650). Size: Diameter 82.0 mm, thickness 3.8 mm at seppa-dai, 3.4 mm at rim. -

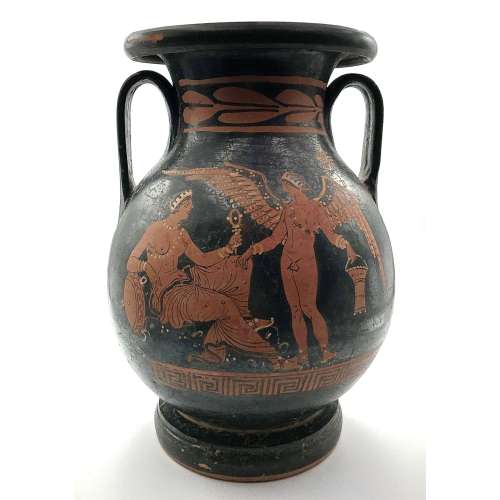

Seller provided description:"Finely painted via the red-figure technique, an elegant pelike vessel of a classic globular form with a cylindrical neck rising to a flared rim, and twin fluted handles, all upon a raised, concave, disc foot.Side A depicts a winged Eros who stands in contrapposto facing toward the left, in the nude save sandals, bracelets, a beaded sash, and a stephane (wreath) holding a situla (pail) in his left hand and gesturing toward the seated maenad before him. Though with her breasts exposed, the maenad does wear a lower garment, and is bedecked with a stephane, multiple bracelets, and strands of pearls around her neck - all delineated in fugitive white and yellow pigment. She holds a mirror in her left upraised hand and leans upon a tambourine with her right elbow. Above and to the right is a maker's mark of a circular format with a central X that is further adorned by nested wedges and dot motifs. Side B presents two opposing standing draped male figures, the gent on the left leaning upon a walking stick. Complementing the figural program, is a lovely decorative program adorning both sides of the vessel, with bands of laurel leaves above and a repeating Greek key/meander below. An outstanding example, masterfully wheel thrown, so that we see absolutely no signs of any jogs in the transitions between the different elements of the vase. Moreover, it presents ideal proportions perfect for presenting the superb painted iconographic/decorative program. The painting was executed with the utmost skill and artistry - the red-figure technique enabling the artist to delineate the figures' musculature, facial details, as well as the cascading drapery folds with extensive fugitive paint embellishments.Expected surface wear with some scuffs and pigment losses commensurate with age, but the painted program is generally very well preserved. Area of repair/restoration to cloak of male on right (Side B). Minute nick to left of male on left (Side B). Nice root marks throughout and areas of encrustation. Thermoluminescence (TL) report: the piece has been found to be ancient and of the period stated. Equivalent age: 2400 +/- 300 years. Certificate of Authenticity from Artemis Gallery. Provenance: private East Coast, USA collection. Greece, Southern Italy, Apulia, ca. 330 BCE.Size: 6.75" in diameter x 9.875" H (17.1 cm x 25.1 cm)Polina de Mauny, being both attentive and knowledgeable, was the first who noticed a possible mistake in the description above. It is highly probable that the woman on side A is not a maenad but Aphrodite herself, holding a mirror and leaning on a shield. Maenads were "often portrayed as inspired by Dionysus into a state of ecstatic frenzy through a combination of dancing and intoxication". The situla, held by Eros, unequivocally alludes to Dionysian ritual, which has to do as much with maenads as with Aphrodite. The nature of two men on side B remain unclear.

Seller provided description:"Finely painted via the red-figure technique, an elegant pelike vessel of a classic globular form with a cylindrical neck rising to a flared rim, and twin fluted handles, all upon a raised, concave, disc foot.Side A depicts a winged Eros who stands in contrapposto facing toward the left, in the nude save sandals, bracelets, a beaded sash, and a stephane (wreath) holding a situla (pail) in his left hand and gesturing toward the seated maenad before him. Though with her breasts exposed, the maenad does wear a lower garment, and is bedecked with a stephane, multiple bracelets, and strands of pearls around her neck - all delineated in fugitive white and yellow pigment. She holds a mirror in her left upraised hand and leans upon a tambourine with her right elbow. Above and to the right is a maker's mark of a circular format with a central X that is further adorned by nested wedges and dot motifs. Side B presents two opposing standing draped male figures, the gent on the left leaning upon a walking stick. Complementing the figural program, is a lovely decorative program adorning both sides of the vessel, with bands of laurel leaves above and a repeating Greek key/meander below. An outstanding example, masterfully wheel thrown, so that we see absolutely no signs of any jogs in the transitions between the different elements of the vase. Moreover, it presents ideal proportions perfect for presenting the superb painted iconographic/decorative program. The painting was executed with the utmost skill and artistry - the red-figure technique enabling the artist to delineate the figures' musculature, facial details, as well as the cascading drapery folds with extensive fugitive paint embellishments.Expected surface wear with some scuffs and pigment losses commensurate with age, but the painted program is generally very well preserved. Area of repair/restoration to cloak of male on right (Side B). Minute nick to left of male on left (Side B). Nice root marks throughout and areas of encrustation. Thermoluminescence (TL) report: the piece has been found to be ancient and of the period stated. Equivalent age: 2400 +/- 300 years. Certificate of Authenticity from Artemis Gallery. Provenance: private East Coast, USA collection. Greece, Southern Italy, Apulia, ca. 330 BCE.Size: 6.75" in diameter x 9.875" H (17.1 cm x 25.1 cm)Polina de Mauny, being both attentive and knowledgeable, was the first who noticed a possible mistake in the description above. It is highly probable that the woman on side A is not a maenad but Aphrodite herself, holding a mirror and leaning on a shield. Maenads were "often portrayed as inspired by Dionysus into a state of ecstatic frenzy through a combination of dancing and intoxication". The situla, held by Eros, unequivocally alludes to Dionysian ritual, which has to do as much with maenads as with Aphrodite. The nature of two men on side B remain unclear. -

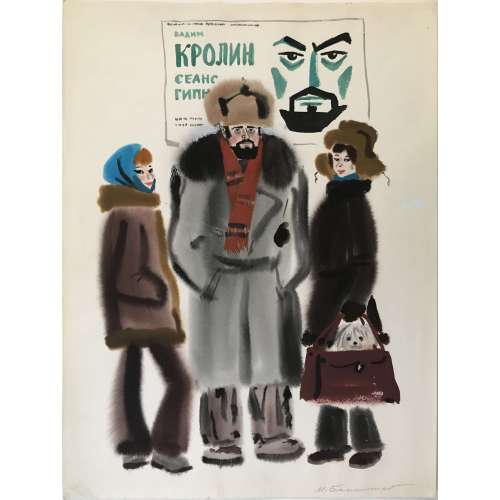

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Vadim Krolin, hypnosis session. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, ca. 1970s. Size: 36 x 48 cm.

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Vadim Krolin, hypnosis session. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, ca. 1970s. Size: 36 x 48 cm. -

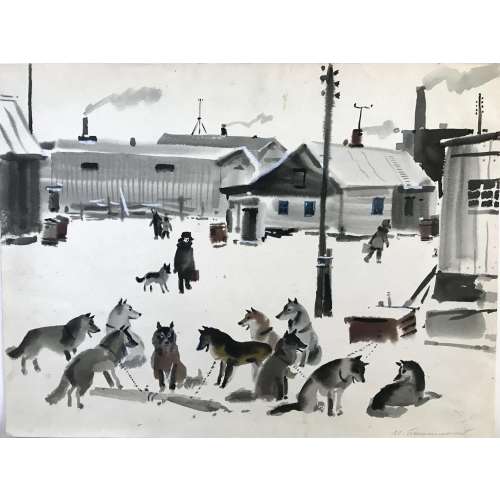

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Village, dogs. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, 1975. Size: 36 x 48 cm.

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Village, dogs. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, 1975. Size: 36 x 48 cm. -

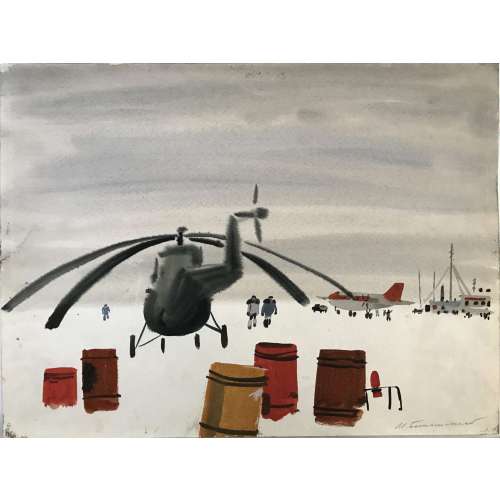

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Helicopter. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, 1975. Size: 36 x 48 cm.

Mikhail Belomlinsky. Born 1934, Russia. Helicopter. Watercolor painting on paper from Chukotka expedition, 1975. Size: 36 x 48 cm. -

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with eight roundels – circular emblems of flowers and/or family crests (mon) made of cast brass, pierced and chiseled in kebori, and with flat brass inlay (hira-zōgan) of vines or leaves all over the plate. Both hitsu-ana could have been trimmed with brass now lacking. Nakago-ana of triangular form, possibly enlarged, with copper sekigane. All typical emblems with bellflower, two variations on suhama theme, and 3, 4, 5, and 6-poinitng mon variations. A distinctive character of this tsuba is a mon at 12 hours depicting water plantain (omodaka).

“Omodaka was also called shōgunsō (victorious army grass); because of this martial connotation, it was a design favored for the crests of samurai families” [Family crests of Japan, Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, California]. Yoshirō school (Kaga-Yoshirō). The Momoyama or early Edo period, beginning of 17th century. Size: Height: 81.4 mm; width: 81.2; thickness 3.8 mm at seppa-dai. -

Ulster Official Scout pocket knife with brown jigged bone plastic handles.

Size: 93 mm (closed); 160 mm (opened); 70 mm blade.

Tang is etched with: Ulster