-

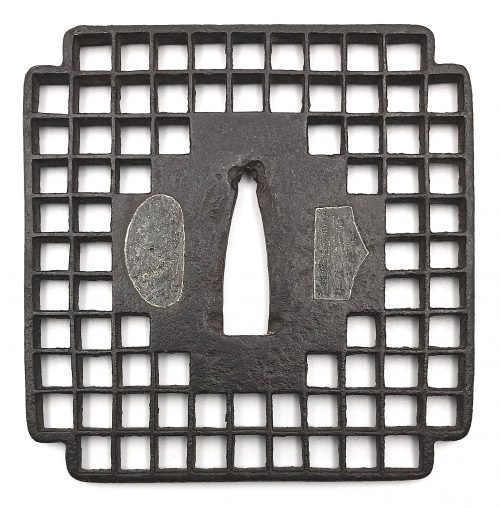

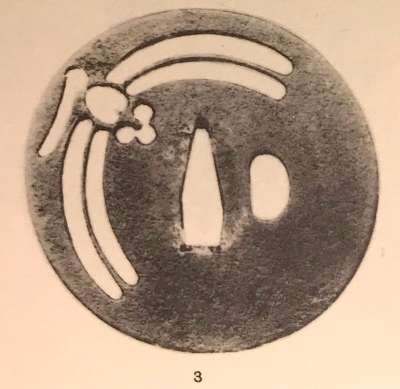

Iron tsuba of round form with design of hatchet executed in openwork (sukashi) and three fan panels motif on both sides carved in low relief (sukidashi-bori). Designs on the fan panels - face: bellflower, plum blossom in mist, grass leaves; - back: clouds, grass, and half plum blossom in mist. Copper sekigane. Koga-hitsu-ana probably cut out on a later date. Kamakura or kamakura-bori school. Edo period. Height: 83.8 mm, Width: 82.2 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 3.2 mm. NBTHK certificate № 4005500: Hozon (worthy of preservation).

Iron tsuba of round form with design of hatchet executed in openwork (sukashi) and three fan panels motif on both sides carved in low relief (sukidashi-bori). Designs on the fan panels - face: bellflower, plum blossom in mist, grass leaves; - back: clouds, grass, and half plum blossom in mist. Copper sekigane. Koga-hitsu-ana probably cut out on a later date. Kamakura or kamakura-bori school. Edo period. Height: 83.8 mm, Width: 82.2 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 3.2 mm. NBTHK certificate № 4005500: Hozon (worthy of preservation). -

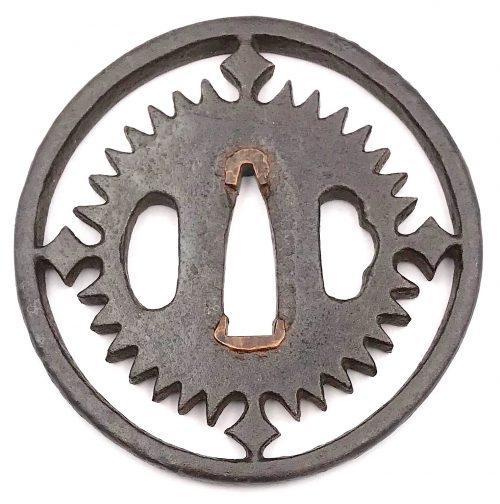

Round iron plate of grey colour decorated in low relief (sukidashi-bori) on the face with sea waves (both layered waves, seigaiha, and rough waves, araumi), sago palm (cycas revoluta, sotetsu), presumably orchid leaves (ran) - five of them - hanging from the above, and reeds (ashi), and on the back with waves (seigaiha only), rocks, chrysanthemums (kiku), clove (chori), reed, and presumably orchid leaves - three of them - hanging from the above. The kozuka-hitsu-ana was probably cut later. The plate is lacking the raised rim, typical for the kamakura-bori school. Muromachi period. Dimensions: Height: 76.8 mm, width: 76.1 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 3.3 mm, at rim 2.0 mm. Height of nakago-ana: 29 mm. Weight: 82.4 g. NBTHK certificate № 402152: Hozon - "Worthy of preservation". A similar (most probably the same) tsuba is illustrated and described at Butterfield & Butterfield. IMPORTANT JAPANESE SWORDS, SWORD FITTINGS AND ARMOR. Auction Monday, November 19th, 1979. Sale # 3063 under lot № 66. It describes the piece as following: “Kamakura bori work of the Muromachi period. Round thin plate with some small iron bones in the edge. Carved with design of plants (sego palm) rocks, and waves on the face. The back has half of two chrysanthemums, waves, clove, and sego palm leaves. The kozuka-hitsu has been added and later enlarged. A good typical example without the rim most have. Diameter: 7.7 cm., thickness 2.5 mm. Estimated price $100-200":

Round iron plate of grey colour decorated in low relief (sukidashi-bori) on the face with sea waves (both layered waves, seigaiha, and rough waves, araumi), sago palm (cycas revoluta, sotetsu), presumably orchid leaves (ran) - five of them - hanging from the above, and reeds (ashi), and on the back with waves (seigaiha only), rocks, chrysanthemums (kiku), clove (chori), reed, and presumably orchid leaves - three of them - hanging from the above. The kozuka-hitsu-ana was probably cut later. The plate is lacking the raised rim, typical for the kamakura-bori school. Muromachi period. Dimensions: Height: 76.8 mm, width: 76.1 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 3.3 mm, at rim 2.0 mm. Height of nakago-ana: 29 mm. Weight: 82.4 g. NBTHK certificate № 402152: Hozon - "Worthy of preservation". A similar (most probably the same) tsuba is illustrated and described at Butterfield & Butterfield. IMPORTANT JAPANESE SWORDS, SWORD FITTINGS AND ARMOR. Auction Monday, November 19th, 1979. Sale # 3063 under lot № 66. It describes the piece as following: “Kamakura bori work of the Muromachi period. Round thin plate with some small iron bones in the edge. Carved with design of plants (sego palm) rocks, and waves on the face. The back has half of two chrysanthemums, waves, clove, and sego palm leaves. The kozuka-hitsu has been added and later enlarged. A good typical example without the rim most have. Diameter: 7.7 cm., thickness 2.5 mm. Estimated price $100-200":

Butterfield & Butterfield, 1979. Sale # 3063, lot № 66.

-

Mokkō-form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) iron plate of grey colour decorated on both sides with waves, reeds, cloud, pagoda, and thatched hut in low relief (sukidashi-bori). The kozuka-hitsu-ana is original, the kogai-hitsu-ana probably cut later (lacks raised rim, fuchidoru). Wide (5.7 mm) raised rim of rounded square dote-mimi type, decorated with fine cross-hatching. Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: Height: 75.9 mm, width: 76.4 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 2.3 mm, at rim 4.4 mm. Kamakura-bori tsuba of such a form is unusual. The rim is also unusual; it is possible that cross-hatching was done as a preparatory step for damascening, or the the damascening (gold or silver) disappeared with passage of time.

Mokkō-form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) iron plate of grey colour decorated on both sides with waves, reeds, cloud, pagoda, and thatched hut in low relief (sukidashi-bori). The kozuka-hitsu-ana is original, the kogai-hitsu-ana probably cut later (lacks raised rim, fuchidoru). Wide (5.7 mm) raised rim of rounded square dote-mimi type, decorated with fine cross-hatching. Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: Height: 75.9 mm, width: 76.4 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 2.3 mm, at rim 4.4 mm. Kamakura-bori tsuba of such a form is unusual. The rim is also unusual; it is possible that cross-hatching was done as a preparatory step for damascening, or the the damascening (gold or silver) disappeared with passage of time.

-

Thin iron plate of round form and black color carved in sukidashi-bori with design of rocks, waves, clouds, temple gates (torii), mountain pavilion and 5-storey pagoda on both sides, alluding to Todai-ji temple in Nara. Hitsu-ana pierced later. Very narrow very slightly raised rim. Copper sekigane.

Late Muromachi period, 16th century. Dimensions: 88.7 x 88.0 x 2.4 mm (seppa-dai), 1.8 mm (base plate).Reference: “Art of the Samurai” on page 232, №140: ”Kamakura tsuba with Sangatsu-do tower and bridge. Muromachi period, 16th century. 83 mm x 80 mm. Unsigned. Tokyo National Museum. The mountain pavilion and bridge carved in sunken relief on the iron tsuba – both part of Tōdai-ji, a temple in Nara – are detailed in fine kebori (line) engraving. As a result of the chiseling used to create the relief, the ground of the piece is relatively thin".

-

The thin, four-lobed iron plate of brownish color is carved on each side with two concentric grooves in the middle of the web, and with four thin scroll lines (handles, kan) that follow the shape of the rim. The hitsu-ana were added at a later date. Copper sekigane. Kamakura-bori school. Muromachi period, circa 1400-1550. Size: Height 80.4 mm, width 79.0 mm, thickness 3.2 mm at seppa-dai and 2.7 mm at the rim. Weight: 97.7 g. NBTHK Certificate №4004241: 'Hozon' attestation. As for the motif: the concentric circles is a widespread and generic design. It is described by John W. Dower [The Elements of Japanese Design, 1985, p. 132, #2201-30] as follows: Circle: Enclosure (wa). As a crest by itself, the cirlce carries obvious connotations of perfection, harmony, completeness, integrity, even peace. [...] Ordinary circles are labeled according to their thickness, with terminology ranging from hairline to "snake's eye". The motif that is described by both Compton Collection and R.E. Haynes as "scrolls", presented by John W. Dower as "Handle (kan): Although probably a purely ornamental and nonrepresentational design in origin, over the centuries this motif acquired the label kan, denoting its resemblance to the metal handles traditionally used on chests of drawers. [...] Very possibly the "handle" motif represents an early abstract version of the popular mokko, or melon pattern." Early Chinese Taoists claimed that special melon was associated with the Eastern Paradise of Mount Horai just as life-giving peaches were associated with the Western Paradise of the Kunlun Mountains. [...] A design motif called mokko (also translated as "melon" in accordance with the two ideographs with which it is written) may have nothing to do with the fruit. Mokko designs... are widely used as crests of both private families and Shinto shrines and are repeated as background designs that evoke a sense of classicism" [Symbols of Japan. Merrily Baird, 2001]. There is a look alike tsuba at Dr. Walter A. Compton Collection, 1992, Christie’s auction, Part II, pp. 14-15, №16:

The thin, four-lobed iron plate of brownish color is carved on each side with two concentric grooves in the middle of the web, and with four thin scroll lines (handles, kan) that follow the shape of the rim. The hitsu-ana were added at a later date. Copper sekigane. Kamakura-bori school. Muromachi period, circa 1400-1550. Size: Height 80.4 mm, width 79.0 mm, thickness 3.2 mm at seppa-dai and 2.7 mm at the rim. Weight: 97.7 g. NBTHK Certificate №4004241: 'Hozon' attestation. As for the motif: the concentric circles is a widespread and generic design. It is described by John W. Dower [The Elements of Japanese Design, 1985, p. 132, #2201-30] as follows: Circle: Enclosure (wa). As a crest by itself, the cirlce carries obvious connotations of perfection, harmony, completeness, integrity, even peace. [...] Ordinary circles are labeled according to their thickness, with terminology ranging from hairline to "snake's eye". The motif that is described by both Compton Collection and R.E. Haynes as "scrolls", presented by John W. Dower as "Handle (kan): Although probably a purely ornamental and nonrepresentational design in origin, over the centuries this motif acquired the label kan, denoting its resemblance to the metal handles traditionally used on chests of drawers. [...] Very possibly the "handle" motif represents an early abstract version of the popular mokko, or melon pattern." Early Chinese Taoists claimed that special melon was associated with the Eastern Paradise of Mount Horai just as life-giving peaches were associated with the Western Paradise of the Kunlun Mountains. [...] A design motif called mokko (also translated as "melon" in accordance with the two ideographs with which it is written) may have nothing to do with the fruit. Mokko designs... are widely used as crests of both private families and Shinto shrines and are repeated as background designs that evoke a sense of classicism" [Symbols of Japan. Merrily Baird, 2001]. There is a look alike tsuba at Dr. Walter A. Compton Collection, 1992, Christie’s auction, Part II, pp. 14-15, №16: The description goes: “A kamakurabori type tsuba, Muromachi period, circa 1400. The thin, six-lobed iron plate is carved on each side with a wide groove that follows the shape of the rim, and with six scroll lines and a single thin circular groove. […] The hitsu-ana was added at a later date, circa 1500-1550. Height 8.3 cm, width 8.6 cm, thickness 2.5 mm. The tsuba was initially intended to be mounted on a tachi of the battle type in use from Nambokucho to early Muromachi period (1333-1400)”. Sold at $935.

And another one in Robert E. Haynes Catalog #9 on page 24-25 under №23:

The description goes: “A kamakurabori type tsuba, Muromachi period, circa 1400. The thin, six-lobed iron plate is carved on each side with a wide groove that follows the shape of the rim, and with six scroll lines and a single thin circular groove. […] The hitsu-ana was added at a later date, circa 1500-1550. Height 8.3 cm, width 8.6 cm, thickness 2.5 mm. The tsuba was initially intended to be mounted on a tachi of the battle type in use from Nambokucho to early Muromachi period (1333-1400)”. Sold at $935.

And another one in Robert E. Haynes Catalog #9 on page 24-25 under №23:

R.E. Haynes description: “Typical later Kamakura-bori style work. This type of plate and carving show the uniform work produced by several schools in the Muromachi period. Some had brass inlay and others were just carved as this one is. The hitsu are later. Ca. 1550. Ht. 8.8 cm, Th. 3.25 mm”. Sold for $175.

R.E. Haynes description: “Typical later Kamakura-bori style work. This type of plate and carving show the uniform work produced by several schools in the Muromachi period. Some had brass inlay and others were just carved as this one is. The hitsu are later. Ca. 1550. Ht. 8.8 cm, Th. 3.25 mm”. Sold for $175.

-

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with a ladle, pestle, mortar, and rice sickle in positive silhouette openwork (nikubori-ji-sukashi). Slightly rounded rim with iron bones (tekkotsu). Seppa-dai plugged with copper fittings (sekigane). Silver patina. The design resembles mochi-making utensils; mochi (rice cake) symbolizes longevity. Kanayama school, c. 1590 (Momoyama period). Note: unusually large size for a Kanayama tsuba: diameter 79.5 mm, thickness at seppa-dai: 5.5 mm, at rim: 6.0 mm. Concerning the design: While the ladle and pestle are clear, the mortar (under the seppa-dai), and the sickle (to the left) require certain imagination.

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with a ladle, pestle, mortar, and rice sickle in positive silhouette openwork (nikubori-ji-sukashi). Slightly rounded rim with iron bones (tekkotsu). Seppa-dai plugged with copper fittings (sekigane). Silver patina. The design resembles mochi-making utensils; mochi (rice cake) symbolizes longevity. Kanayama school, c. 1590 (Momoyama period). Note: unusually large size for a Kanayama tsuba: diameter 79.5 mm, thickness at seppa-dai: 5.5 mm, at rim: 6.0 mm. Concerning the design: While the ladle and pestle are clear, the mortar (under the seppa-dai), and the sickle (to the left) require certain imagination. -

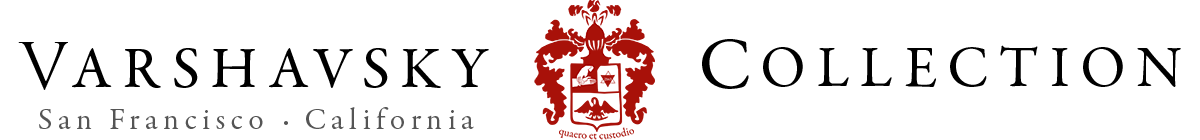

Iron tsuba of round form with design of slanting rays of light (shakoh) or clock gear (tokei) in openwork (sukashi). Commonly considered a Christian / Jesuit motif. Round-cornered rim. Copper sekigane. Momoyama period: Late 16th century (Tensho/Keicho era). Height: 72.5 mm, Width: 72.2 mm, Rim thickness: 5.5 mm, Center thickness: 5.3 mm. Round-cornered rim. Provenance: Sasano collection. Sasano Masayuki, Japanese Sword Guards Masterpieces from The Sasano Collection, Part I, № 136: "The general belief that this design represents the gear of a clock is erroneous, rather it shows the slanting rays of light from a cross, with the small diamond shapes representing the upright and transverse bars. The Christian influence is obvious..."

Iron tsuba of round form with design of slanting rays of light (shakoh) or clock gear (tokei) in openwork (sukashi). Commonly considered a Christian / Jesuit motif. Round-cornered rim. Copper sekigane. Momoyama period: Late 16th century (Tensho/Keicho era). Height: 72.5 mm, Width: 72.2 mm, Rim thickness: 5.5 mm, Center thickness: 5.3 mm. Round-cornered rim. Provenance: Sasano collection. Sasano Masayuki, Japanese Sword Guards Masterpieces from The Sasano Collection, Part I, № 136: "The general belief that this design represents the gear of a clock is erroneous, rather it shows the slanting rays of light from a cross, with the small diamond shapes representing the upright and transverse bars. The Christian influence is obvious..." -

Iron tsuba of round form with design of the Chinese character for cinnabar (shu-no-ji) in openwork (sukashi). Round-cornered rim. Copper sekigane. Kanayama school. Early Edo period: Early 17th century (Kan-ei era). Height: 70.0 mm. Width: 69.6 mm. Rim thickness: 6.8 mm. Center thickness: 5.8 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 139: "Many areas have a coarse texture and strong tekkotsu, with the thickness of the metal graduating from the rim to the seppa-dai. The combined color of the iron and motif date this work to the early Edo period".

Iron tsuba of round form with design of the Chinese character for cinnabar (shu-no-ji) in openwork (sukashi). Round-cornered rim. Copper sekigane. Kanayama school. Early Edo period: Early 17th century (Kan-ei era). Height: 70.0 mm. Width: 69.6 mm. Rim thickness: 6.8 mm. Center thickness: 5.8 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 139: "Many areas have a coarse texture and strong tekkotsu, with the thickness of the metal graduating from the rim to the seppa-dai. The combined color of the iron and motif date this work to the early Edo period". -

A very thin kobushi-gata form iron tsuba decorated in openwork (sukashi), some openings filled with grey metal (silver or pewter) treated in a way to resemble cracked ice, ginkgo leaf to recto and plum blossoms to verso in low-relief (takabori) and gold inlay (zōgan), and unevenly folded over rim (hineri-mimi). The overall theme of the piece is linked to the icy ponds, falling ginkgo leaves and blossoming plums in the late winter.

Size: 84 x 80 mm, thickness (center): 2 mm.Signed: Yamashiro no kuni Fushimi no ju Kaneie [Kaneie of Fushimi in Yamashiro Province] [山城國伏見住金家], with Kaō.

Probably the work of Meijin-Shodai Kaneie (c. 1580 – 1600).

The silver or pewter inlays likely a later work that may be attributed to Goto Ichijo (1791 – 1876) or one of his apprentices in the late 19th century, possibly as a tribute to the great Kaneie masters. Here is an article by Steve Waszak dedicated to Kaneie masters and this tsuba in particular.Kaneie

For many tosogu aficionados, this name reigns supreme among all tsubako across Japanese history. The first Kaneie is celebrated for many things. He is recognized as being the first ever to bring pictorial landscape subjects to a canvas so small as that of a tsuba plate. His skill in being able to render classical Chinese landscape themes while working with a material as unyielding as steel, and to do so with the sensitivity he does, is nothing short of astounding. The quality of his workmanship — especially that of his exquisitely carved motif elements and the extraordinary deftness of his tsuchime (槌目 or 鎚目, hammer-blow) utilizing such thin plates — astonishes even to this day. His sensibilities concerning the shaping of his sword guards and the presentation of the rims were no less innovative than his subject matter. He was among the very first to regularly sign his name as a tsuba smith. And it is likely that he served the great warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the latter years of the 16th century. Despite the great fame and reputation of Kaneie, very little of the lives of the two men who are seen by most scholars as the “true Kaneie” tsubako of the Momoyama and earliest Edo Periods is known to us now. They were both smiths working in steel, with occasional added soft-metal inlay (usually serving to highlight features), and both made sword guards of the same style, using subject matter focused on landscapes, allusions to historical events, or religious themes. The first of these men is often referred to as “O-Shodai,” or Great First Generation, while the second is known as “Meijin-Shodai,” or Famous First Generation. While some see subsequent generations stemming from these first two men, others have the O-Shodai and the Meijin-Shodai as THE two true Kaneie and make a sharp distinction between these two smiths and any others who may share the name.The work of the O-Shodai may appear with two different mei. One of these is written “Joshu Fushimi Ju Kaneie,” while his work may also carry a mei reading “Yamashiro no Kuni Fushimi Ju Kaneie.” It is thought by some scholars that the earlier works present with the “Joshu” mei, while his later works feature the “Yamashiro” mei. However, there are only some five or six tsuba extant with the “Joshu” signature, so we should not necessarily see works with the “Yamashiro” signature as dating only to the latest years of his working life. The answers to the questions of exactly when Kaneie might have begun his life as a tsubako, or how old he was when he moved to sign his works with the “Yamashiro” mei, will probably remain shrouded in uncertainty.The association between Kaneie and Toyotomi Hideyoshi is speculative, to be sure, but the circumstantial evidence is tantalizing. The area of Fushimi is thought to have been an entirely unremarkable land prior to Hideyoshi’s building of a castle there, so it would seem unlikely that the first Kaneie would have been working in such a nondescript place, much less including the place name in his mei, before Hideyoshi’s putting it on the map, so to speak. Why emphasize such pride of place in one’s signature unless the place itself carries a certain weight? The name “Kaneie” translates roughly to “gold family,” which, given Hideyoshi’s notorious love of gold, would seem too much of a coincidence when combined with the explicit mention of Fushimi in the signatures. Combine this with the consideration of what is an equally compelling relationship between the celebrated tsubako Nobuie and Oda Nobunaga (“Nobuie” means roughly “of the family of “Nobu”), whom Hideyoshi served as a top general until Oda’s demise in 1582, and the circumstantial evidence becomes even harder to deny the plausibility of. Oda, ever the innovator, may have been the one responsible for birthing the practice of tsubako regularly signing their works. Having a superb smith like Nobuie affix the name to the tsuba as a regular practice establishes a sort of “brand name,” a brand coming with the seal of approval of Oda Nobunaga. It is more than possible that Nobunaga may have then used these valuable sword guards as rewards given to vassals and other important relations to honour them for their services to him, a practice that would have allowed Nobunaga to avoid having to use gold, guns, swords, horses, or land to do so. The awarding of a magnificent Nobuie tsuba to a deserving warrior, an appreciated ally, or a family member would bring honour to the recipient, of course, but would also honour the maker of the sword guard, and even the giver of the object. Such a way of thinking would be absolutely typical of him, and given that both Oda Nobunaga and Nobuie were men of Kiyosu in Owari in the early Momoyama Period, it does not strain credulity to imagine that the above dynamic could have occurred in just this way. If indeed it did, Toyotomi Hideyoshi is unlikely to have let this pass unnoticed. He may even have been so honoured himself! When he rose to power very shortly after Oda’s death, then, and when he reinforced and consolidated that power in the late 1580s and early 1590s, which included the building of the castle at Fushimi, perhaps he sought to emulate the Oda vision and practice of establishing a “royal tsubako.” If so, Kaneie would have been that smith.As noted, this scenario is speculative, and not a little romantic. This does not mean, however, that it is in fact not likely, for there would be a number of coincidences involved for it to be entirely false.Tsuba scholars will say that Kaneie’s skills in the making of his sword guards indicate an armour-making background. This is an interesting viewpoint, but one can’t help but wonder how many armourers were possessed of such fluent literacy in lyrical Chinese historical tales that they could then represent them as motifs on steel plates. Kaneie subjects often are in the form of Chinese landscapes and allusions, as noted, one of which — The Eight Views of the Xiao and the Xiang — was very well known as a famous subject of Chinese painting and poetry from the Song Dynasty. There exist Kaneie tsuba which depicts at least some of these “views,” and it seems unlikely that if one or more of them were to be created, not all of them would be, in a sort of “series.” The cultural and literary fluency Kaneie would seem to have had, then, may suggest a Buddhist background, and indeed, some of the subjects seen are explicitly Buddhist in nature. Perhaps his background then, somehow offering a dovetailing of metalwork and Buddhist teachings; in any event, we are all the richer for at least some of the works of Kaneie to have survived to reach us today.One of the hallmarks of Kaneie tsuba (real ones) is the extreme thinness of the plate, combined with utterly superb tsuchime expression of that plate. To be able to hammer the plate to achieve such strength of expression while the plate is so thin is seen by the Japanese as practically miraculous. A notable and important kantei point between the early masterpieces by the two “Shodai” Kaneie and the tsuba made by followers is this thinness of the plate. Another kantei point: because the plate is so thin when raised areas representing motif elements are present, they are inlaid into the plate, because trying to carve them from such a thin plate would be practically impossible: the likelihood of piercing the plate would be high, and the plate in that area, even if not pierced, would be significantly weakened by trying to manage the raising of a motif element from the plate. In real Kaneie works, then, one would expect any raised motif elements to be inlaid.Other highlights: the “Shodai” Kaneie are famous for the kobushi-gata (拳形) or “fist-shaped” design in their work, but despite this, there actually aren’t that many extant sword guards boasting this shape. Another feature for which the Kaneie are justly famous is their folding over of the lip of the rim onto the plate in a very tasteful manner, just here and there, rather than uniformly across the tsuba. However, again, this feature is actually not commonly seen, either. The combination, then, of a kobushi-gata shape with the rim folded over in just a few areas is that much rarer.Which brings us to the featured piece.Here is a Kaneie tsuba, a “Meijin-Shodai” Kaneie, which presents with a very thin plate, being between 1.5 and 2mm in thickness. The motif elements are inlaid, as we should expect. The sugata (姿, shape) is Kobushi-gata with the rim folded over in only a few places, representing a relatively infrequently encountered form, as stated. The tsuba here is fortunate not to have any added hitsu-ana, unlike many or most other Kaneie do. The sukashi elements are fascinating to consider, being difficult to determine the meaning of; however, the raised elements clearly point to a seasonal motif, with cherry and plum blossoms on the omote for Spring, and ginkgo on the ura for Fall. The inlaid metal in two of the openings — silver, shibuichi, or pewter, perhaps — is very likely a later addition, probably 19th-century, and more specifically, late-19th-century. The finishing on these inlaid portions has all the hallmarks of Goto Ichijo workmanship. Namely, the treatment of the surface of the inlay to resemble fallen snow (in the Japanese sense of things) is expressed in a very Ichijo sense of things, and, given the great importance of Kaneie tsuba, and the seasonal expression the motif of the guard has, it is plausible that the inlay is Ichijo work or that of one of his top students. In any event, this inlay complements the rest of the tsuba beautifully. The inlay also resembles the art of kintsugi (金継ぎ, golden joinery) or the Japanese practice of ceramic repair using lacquer when a piece is particularly special or important. In this way, a nod is given to Tea Culture, too, creating a wonderful blending of associations and allusions, typical of the highest Japanese aesthetic sense.At 8.4cm, the tsuba is of an excellent size and is in great condition (no rust, no deep rust pitting, no fire damage). There is, intriguingly, one small sign of battle damage at 6:00 on the guard: it would seem a sword blow cut into the tsuba at the rim, and penetrated slightly into the plate. The superb repair represented by a little stitch or two right at the rim and along a few millimetres of the plate is visible on very close inspection. The repair is old, probably nearly contemporary with when the tsuba was made. Given the high status of Kaneie in their lifetime (as tsubako for Hideyoshi, one might imagine their importance), and given the obvious high quality of this piece, it is not surprising that the finest repair efforts were put into its care.The name Kaneie justly enjoys its fame and accolades as pre-eminent among the tens of thousands of tsubako in Japanese history. We are fortunate indeed to have had a small number of the works of the early masters survive to this day. The first of their kind, and as most scholars and aficionados would wholeheartedly agree, the best of their kind, Kaneie sword guards remain among the very finest examples of the Japanese metal-working traditions. -

Iron tsuba with hammer marked surface and design of a plum and cherry blossoms to the right of nakaga-ana in openwork (sukashi). Raised rim, typical to katchushi school. The thickness of the plate provides for later Muromachi period making.

Late Muromachi period (1514-1573). Size: 85.8 x 85.0 x 3.6 (center), 4.1 (rim) mm; weight: 136 g. -

Iron tsuba of circular form with a branch of loquat (biwa) pierced in positive silhouette (ji-sukashi) and carved in marubori technique (marubori-sukashi). Kozuka and kogai hitsu-ana are plugged with shakudo.

Signature: Choshu Kawaji ju Hisatsugu saku. Chōshū school in Nagato province.

According to M. Sesko 'Genealogies' Hisatsugu was a 4th generation Kawaji School master from Chōshū (present day Nagato), with the name Gonbei, formerly Toramatsu, adopted son of Tomohisa (1687-1743) [page 117]. For Tomohisa work see TSU-0104 in this collection. -

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of moon, stars, cloud, snowflake, gorintō, and Genji-mon in negative openwork (in-sukashi). Raised tubular rim (dote-mimi). Deep black patina, traces of lacquer. Naka-daka type of plate (thicker in center, getting thiner towards the rim). Visible gap between the rim and the plate. Dimensions: Height: 91.7 mm; Width: 90.8 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 2.5 mm, plate before rim: 2.2 mm, of the rim: 5.6 mm. At least Mid Muromachi period, 15th century, but possibly earlier. In 'Silver Book', commenting tsuba №34 Sasano writes: "The technique used to create the rim is the same used for the peak (koshimaki) of helmets (kabuto) during the Kamakura and Nanbokucho periods." On the other hand, the abundance of sukashi elements points towards later times, perhaps late Muromachi or even Momoyama period. "Gorintō is a grave stone composed of five pieces, piled on one the other, representing, from the bottom upward, earth, water, fire, wind, and heaven, respectively" [Nihon Tō Kōza, Volume VI, Part 1. AFU, 1993, p. 6. / LIB-1554]. A romantic description of the piece may look like this: The air is scented (incense symbol); it's a graveyard, marked by gorintō; a winter (snowflake) evening or night (moon, stars); mist is rising from a ravine towards moon. I did not manage to find a katchūshi piece of this design, only a few Kamakura-bori tsuba:

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of moon, stars, cloud, snowflake, gorintō, and Genji-mon in negative openwork (in-sukashi). Raised tubular rim (dote-mimi). Deep black patina, traces of lacquer. Naka-daka type of plate (thicker in center, getting thiner towards the rim). Visible gap between the rim and the plate. Dimensions: Height: 91.7 mm; Width: 90.8 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 2.5 mm, plate before rim: 2.2 mm, of the rim: 5.6 mm. At least Mid Muromachi period, 15th century, but possibly earlier. In 'Silver Book', commenting tsuba №34 Sasano writes: "The technique used to create the rim is the same used for the peak (koshimaki) of helmets (kabuto) during the Kamakura and Nanbokucho periods." On the other hand, the abundance of sukashi elements points towards later times, perhaps late Muromachi or even Momoyama period. "Gorintō is a grave stone composed of five pieces, piled on one the other, representing, from the bottom upward, earth, water, fire, wind, and heaven, respectively" [Nihon Tō Kōza, Volume VI, Part 1. AFU, 1993, p. 6. / LIB-1554]. A romantic description of the piece may look like this: The air is scented (incense symbol); it's a graveyard, marked by gorintō; a winter (snowflake) evening or night (moon, stars); mist is rising from a ravine towards moon. I did not manage to find a katchūshi piece of this design, only a few Kamakura-bori tsuba:

100 selected tsuba from European collections. Catalogue by Robert Haynes and Robert Burawoy, 1984, page 16, №5.

While the upper tsuba is dated end of Muromachi, the lower is attributed to the 17th century - Momoyama or early Edo period, though the author put this attribution under question. Deciphering of the strangely shaped opening to the left of nakago-ana is sometimes "a conventional scroll", and sometimes - a fern or bracken. I think mine is a cloud or mist, but I don't have any material evidence proving this understanding and came to conclusion by context only. It may easily be a dinosaurs playing ball. The fact that this thing always accompanies the Genji-mon, or incense symbol, it may be a scent itself.

Japanese Sword Fittings. Collection of G.H. Naunton, Esq., by Henri L. Joly, - 1912; №9.

-

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of pine tree mushrooms (matsutake) in openwork (sukashi). Hitsu-ana of elongated oval form. Raised rim (mimi) with iron bones (tekkotsu). Copper sekigane. Size: 84.5 mm x 85.1 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm (center), 5.6 mm (rim). Mid Muromachi period, 15th century. The shape and width of the rim, as well as the shape of the hitsu-ana, argue for earlier Muromachi. Tsuba is slightly wider than high, that might suggest middle of Muromachi age. According to Robert Haynes, circa 1450-1500.

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with design of pine tree mushrooms (matsutake) in openwork (sukashi). Hitsu-ana of elongated oval form. Raised rim (mimi) with iron bones (tekkotsu). Copper sekigane. Size: 84.5 mm x 85.1 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm (center), 5.6 mm (rim). Mid Muromachi period, 15th century. The shape and width of the rim, as well as the shape of the hitsu-ana, argue for earlier Muromachi. Tsuba is slightly wider than high, that might suggest middle of Muromachi age. According to Robert Haynes, circa 1450-1500. -

Iron tsuba of circular form with design of pine trees (matsu) and monkey toys (kukurizaru) in openwork (ko-sukashi). Ko-Katchushi school.

Raised rim (mimi) with iron bones (tekkotsu). Size: Diameter: 99.5 mm; Thickness: 2.1 mm at centre; 4.3 mm at the rim.Early Muromachi period: 15th century (Kakitsu - Bun'an era, 1441 - 1449).

-

Iron tsuba of round form with design of diamond-shaped family crest (waribishi-mon) in openwork (sukashi). Bevelled, raised rim. Kozuka-hitsu-ana plugged with tin or lead. Ko-Katchushi school. Early Muromachi period: Early 15th century (Oei era). Size: Height: 89.3 mm. Width: 89.0 mm. Rim thickness: 4.3 mm. Center thickness: 2.9 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 41: "In this tsuba, a family crest incorporating four lozenges sits upright on the right side of the nakago-ana. The straight lines of the lozenge add substance and power. Initially, the crest creates confusion regarding the age, yet the overall impression is one lacking in vigor and probably dates rather later than Nanbokucho period".

Iron tsuba of round form with design of diamond-shaped family crest (waribishi-mon) in openwork (sukashi). Bevelled, raised rim. Kozuka-hitsu-ana plugged with tin or lead. Ko-Katchushi school. Early Muromachi period: Early 15th century (Oei era). Size: Height: 89.3 mm. Width: 89.0 mm. Rim thickness: 4.3 mm. Center thickness: 2.9 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 41: "In this tsuba, a family crest incorporating four lozenges sits upright on the right side of the nakago-ana. The straight lines of the lozenge add substance and power. Initially, the crest creates confusion regarding the age, yet the overall impression is one lacking in vigor and probably dates rather later than Nanbokucho period". -

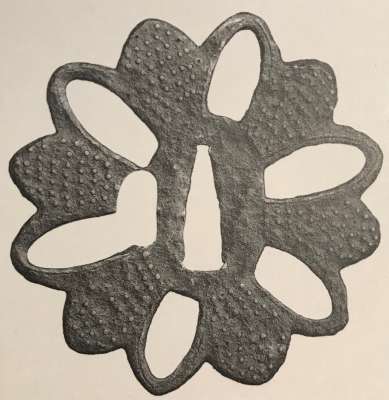

Yamagane tsuba of round form with design of a 14 petal chrysanthemum (kiku) in cast openwork (sukashi), with slightly raised rounded rim. Early Muromachi period (1393-1457). Size: Height: 64.5 mm; Width: 64.0 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 4.1 mm; Weight: 52.5 g. Provenance: Sasano collection (though not illustrated in the book 'Sasano: Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994', which only covers tsuba made of iron). Wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) by Sasano Masayuki. References: Illustrated on p. 140 at Tosogu: Treasure of the samurai by Graham Gemmell in the article Muromachi period tsuba by Robin Peverett, London, 1991, pp. 131-145. Sold at Sotheby's, London, Thursday 10 April 1997 Sotheby's, London, 1997 [Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A.Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections], p. 16: "A ko-kinko bronze Tsuba, early Muromachi period (1393-1453) of circular form, with raised rounded rim, pierced with kiku petals and with a small elongated kozuka-hitsu, the work appearing to be cast and finished by hand. 6.4cm, thickness at centre 4.15mm, at rim 4.8mm. With a Tomobako, bearing a hakogaki by Masayuki Sasano, with rating Shu. Estimated: £1,000-1,500." Hakogaki (courtesy M. Sesko): 古金工 鐔 Ko-Kinkō tsuba 菊花透 無銘 山銅地透 時代 室町前期 古雅入念 秀作 昭和戊辰年伏月 素心鑑 kikka-sukashi, mumei yamagane, ji-sukashi jidai Muromachi-zenki koga nyūnen, shūsaku Showa tsuchinoe-tatsudoshi fukugetsu Soshinkan Kikka-sukashi, unsigned. Of yamagane and with ji-sukashi. Era is early Muromachi period. Excellent and carefully made work of classical elegance. June in the year of the dragon of the Shōwa era (1988) Soshinkan (pen name of Sasano Masayuki).

Yamagane tsuba of round form with design of a 14 petal chrysanthemum (kiku) in cast openwork (sukashi), with slightly raised rounded rim. Early Muromachi period (1393-1457). Size: Height: 64.5 mm; Width: 64.0 mm; Thickness at seppa-dai: 4.1 mm; Weight: 52.5 g. Provenance: Sasano collection (though not illustrated in the book 'Sasano: Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994', which only covers tsuba made of iron). Wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) by Sasano Masayuki. References: Illustrated on p. 140 at Tosogu: Treasure of the samurai by Graham Gemmell in the article Muromachi period tsuba by Robin Peverett, London, 1991, pp. 131-145. Sold at Sotheby's, London, Thursday 10 April 1997 Sotheby's, London, 1997 [Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A.Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections], p. 16: "A ko-kinko bronze Tsuba, early Muromachi period (1393-1453) of circular form, with raised rounded rim, pierced with kiku petals and with a small elongated kozuka-hitsu, the work appearing to be cast and finished by hand. 6.4cm, thickness at centre 4.15mm, at rim 4.8mm. With a Tomobako, bearing a hakogaki by Masayuki Sasano, with rating Shu. Estimated: £1,000-1,500." Hakogaki (courtesy M. Sesko): 古金工 鐔 Ko-Kinkō tsuba 菊花透 無銘 山銅地透 時代 室町前期 古雅入念 秀作 昭和戊辰年伏月 素心鑑 kikka-sukashi, mumei yamagane, ji-sukashi jidai Muromachi-zenki koga nyūnen, shūsaku Showa tsuchinoe-tatsudoshi fukugetsu Soshinkan Kikka-sukashi, unsigned. Of yamagane and with ji-sukashi. Era is early Muromachi period. Excellent and carefully made work of classical elegance. June in the year of the dragon of the Shōwa era (1988) Soshinkan (pen name of Sasano Masayuki). -

A yamagane (unrefined copper) ko-kinko tsuba of slightly elongated round form with design of wisteria carved in sculptural relief (nikubori). Copper sekigane. Unsigned. Muromachi period, likely the 16th century.

A yamagane (unrefined copper) ko-kinko tsuba of slightly elongated round form with design of wisteria carved in sculptural relief (nikubori). Copper sekigane. Unsigned. Muromachi period, likely the 16th century.Size: 74.3 x 71.8 x 3.2 mm.

NBTHK certificate №4003986: Hozon (worthy preservation). In custom wooden box. -

Two ymagane tsuba (daisho) with chiseled diaper pattern of waves. The larger tsuba (dai) is of mokkō form with a wide (4.6 mm) polished rim (fukurin?). Water spray is realized in copper ten-zōgan. Size: 75.0 x 71.6 x 3.2 (center), 4.0 (rim) mm. Copper sekigane. The smaller tsuba (sho) is of oval form, without a rim. No inlay. Size: 53.2 x 45.5 x 4.1 mm. Ko-kinko school. Muromachi period. In Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 5th International Convention & Exhibition, 2009 on page 51 under № 5-U8 there is a piece from George Gaucys collection, described as follows: Unsigned Tachi-Kanagushi tsuba, Yamagane base. Nami (wave) motif. Circa: Muromachi period (15th century). 6.88 x 6.81 x 0.45 (rim), 0.36 (center). The classic wave form is typically seen in Muromachi period tosogu. The patina is rich and rustic, which presents history and warmth. This tsuba may be interpreted as either tachi-kanagushi or ko-kinko work. Early tachi tsuba were symmetrical in design and also not very sophisticated, Design elements filled in up to seppadai as the waves do in this tsuba. There is a simple fikurin of the same metal and it is flat to the plate. On the ko-kinko side, the crests of the waves show more complexity than tachi works and less symmetry. A very intriguing tsuba from late Muromachi period."

Two ymagane tsuba (daisho) with chiseled diaper pattern of waves. The larger tsuba (dai) is of mokkō form with a wide (4.6 mm) polished rim (fukurin?). Water spray is realized in copper ten-zōgan. Size: 75.0 x 71.6 x 3.2 (center), 4.0 (rim) mm. Copper sekigane. The smaller tsuba (sho) is of oval form, without a rim. No inlay. Size: 53.2 x 45.5 x 4.1 mm. Ko-kinko school. Muromachi period. In Kokusai Tosogu Kai; 5th International Convention & Exhibition, 2009 on page 51 under № 5-U8 there is a piece from George Gaucys collection, described as follows: Unsigned Tachi-Kanagushi tsuba, Yamagane base. Nami (wave) motif. Circa: Muromachi period (15th century). 6.88 x 6.81 x 0.45 (rim), 0.36 (center). The classic wave form is typically seen in Muromachi period tosogu. The patina is rich and rustic, which presents history and warmth. This tsuba may be interpreted as either tachi-kanagushi or ko-kinko work. Early tachi tsuba were symmetrical in design and also not very sophisticated, Design elements filled in up to seppadai as the waves do in this tsuba. There is a simple fikurin of the same metal and it is flat to the plate. On the ko-kinko side, the crests of the waves show more complexity than tachi works and less symmetry. A very intriguing tsuba from late Muromachi period."

Kokusai Tosogu Kai 5th, 2009, p. 51, № 5-U8: ko-kinko or tachi-kanagushi tsuba.

-

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of oval form with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.7 mm wide. Possibly, early Mino (ko-Mino) school. Size: 66.6 x 59.9 x 4.0 mm. Some connoisseurs believe that this kind of tsuba was in mass production at the time. Small animal believed to be a fox, however some attribute it to a long-tailed rabbit or a squirrel. I am leaning towards the rabbit. Similar example is found at Robert E. Haynes Catalog №3, April 9-11, 1982 on page 11, under № 15: “Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm” [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. The only difference betwen my tsuba and his is that his has a square hole on the right shoulder of the seppa-dai. Early Muromachi (if we follow Robert it is even Nanbokucho, 1337-1392) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that “waves and rabbit” motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Mokkōgata tsuba of similar design in this collection - see TSU-0282.

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of oval form with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.7 mm wide. Possibly, early Mino (ko-Mino) school. Size: 66.6 x 59.9 x 4.0 mm. Some connoisseurs believe that this kind of tsuba was in mass production at the time. Small animal believed to be a fox, however some attribute it to a long-tailed rabbit or a squirrel. I am leaning towards the rabbit. Similar example is found at Robert E. Haynes Catalog №3, April 9-11, 1982 on page 11, under № 15: “Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm” [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. The only difference betwen my tsuba and his is that his has a square hole on the right shoulder of the seppa-dai. Early Muromachi (if we follow Robert it is even Nanbokucho, 1337-1392) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that “waves and rabbit” motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Mokkōgata tsuba of similar design in this collection - see TSU-0282.

TSU-0282: Ko-kinko yamagane tsuba with waves and rabbit motif.

-

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of mokko form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.4 mm wide. A look-a-like tsub of oval form instead of mokko-gata is illustrated at Robert E. Haynes's Catalog #3,1982 on page 11, lot 15: "Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm" [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. Muromachi (if we follow Robert) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that "waves and rabbit" motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Size: 68.5 x 59.8 x 4.0 mm. NBTHK Certificate № 423120. This tsuba is listed at Yakiba website with the following passage: "Attributions as well as dating of this type of tsuba has been the subject debate over the years. There are those who believe these type of tsuba to be ko-Mino (early Mino School) tsuba, others believe them to be tachi-kanaguchi tsuba. Still others insist they are simply ko-kinko (early soft metal) tsuba. This tsuba was authenticated and determined to be "Ko-Kinko" by the NBTHK". Oval form tsuba with the same design can be found in this collection - TSU-0323.

Ko-kinko ymagane cast tsuba of mokko form (kirikomi-mokkō-gata) with chiseled diaper pattern of double head waves on both sides and a rabbit cast and carved with its eye inlaid in yellow metal (gold or brass) on the face. Fukurin which holds together the sandwiched layers of metal (sanmai) is about 2.4 mm wide. A look-a-like tsub of oval form instead of mokko-gata is illustrated at Robert E. Haynes's Catalog #3,1982 on page 11, lot 15: "Rare design in style of Sanmai (three layers) / Wasei work. With yamagane core and heavy rim cover. The web plates are carved with double head Goto style waves and the face has a fox. The web plates were riveted at the seppadai. See Lot 4, page 8. Ca. 1350. Ht. 6.6 cm, th. 3 mm" [underscore mine]. Quality of photo is so poor that I decided not to provide it here. Muromachi (if we follow Robert) or Momoyama period. The Momoyama attribution is mostly based on a fact that "waves and rabbit" motif became most popular in Momoyama times. Size: 68.5 x 59.8 x 4.0 mm. NBTHK Certificate № 423120. This tsuba is listed at Yakiba website with the following passage: "Attributions as well as dating of this type of tsuba has been the subject debate over the years. There are those who believe these type of tsuba to be ko-Mino (early Mino School) tsuba, others believe them to be tachi-kanaguchi tsuba. Still others insist they are simply ko-kinko (early soft metal) tsuba. This tsuba was authenticated and determined to be "Ko-Kinko" by the NBTHK". Oval form tsuba with the same design can be found in this collection - TSU-0323.

TSU-0323. Ko-kinko yamagane tsuba with waves and rabbit motif.

-

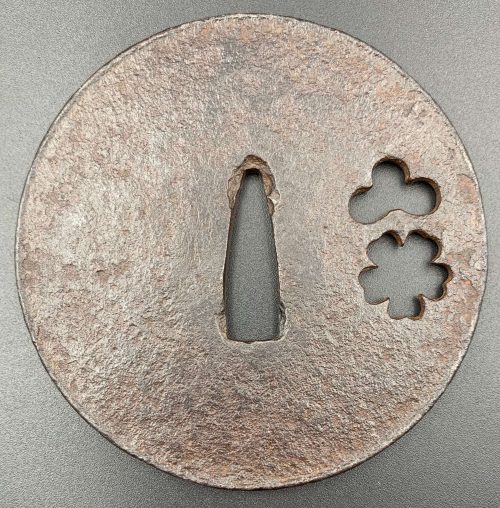

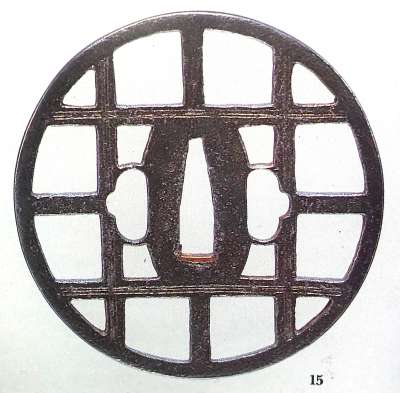

Iron tsuba of square with cut-off edges form (sumi-iri-kakugata) with lattice design in openwork (sukashi) and solid center. Hitsu-ana plugged with lead.

Unsigned. Late Muromachi period, ca. 16th century.

Size: 81.3 x 80.0 x 3.6 mm References: 1) Tsuba Kanshoki. Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975, p. 95, lower image. It's also called Kyō shōami. 2) KTK-11: Koshi motif, Late Muromachi (16th c.) -

Iron tsuba of square with cut-off edges form (sumi-iri-kakugata) with lattice design in openwork (sukashi) and pierced center.

Unsigned. Late Muromachi period, ca. 16th century.

Size: 73.2 x 72.4 x 3.6 mm References: 1) Tsuba Kanshoki. Kazutaro Torogoye, 1975, p. 95, lower image. It's also called Kyō shōami. 2) KTK-11: Koshi motif, Late Muromachi (16th c.) -

Iron tsuba of round form decorated with a deer and maple leaves in positive silhouette openwork (ji-sukashi), with details finely carved in low relief (kebori). Nakagō-ana plugged with copper fittings (sekigane). Traces of lacquer on the surface.

NBTHK: Hozon, №424947.

Design: An autumnal tsuba with an allusion to Kasuga Shrine in Nara.

Attributed by NBTHK to Shoami. Age: Probably the Momoyama period (1574 – 1603) or early Edo period (1603 – 1650), but judging on the item's substantial size (diameter 86.6 mm) and considerable thinness (3.4 mm) may be attributed to earlier times (late Muromachi period, 1514 – 1573). -

Iron tsuba of round form with design of lattice (kōshi-mon, 格子文) cut in openwork (sukashi), with low relief shallow linear carving along the bars. Well forged plate with brown-ish hue. To the right of nakago-ana there is a clear inscription of the character Shō (正), which is explained by Markus Sesko is follows: "The Shinsa obviously recognized more from the signature when having the tsuba in hand, i.e. they were confident to say it is signed "Shōami" but the rest is illegible (ika-fumei, 以下不明). That is, if they were just able to read the first character SHŌ (正) and saw that there were two more, most likely A (阿) and MI (弥), they would have put those character in boxes on the paper. Boxes around characters namely means that the character is not 100% legible but it can be assumed what it is." Momoyama or early Edo period. Dimensions: 85.9 mm diameter, 3.6 mm thickness at seppa-dai. Weight: 79 g. NBTHK certificate № 425069 with attestation: Hozon - "Worthy of preservation". A similar tsuba is presented at Japanese Sword Fittings from the R. B. Caldwell Collection. Sale LN4188 "HIGO". Sotheby's, 30th March 1994, №15. The description says: "A rare early Kamakura-bori tsuba. Nambokucho period (late 14th century). Of circular form, the dark plate carved and pierced with a gate design, the struts with double engraved lines. Unsigned. 8.5 cm." The lot was sold for 1,840 GBP.We have two possible explanations of the discrepancy between Sotheby's and Shinsa/Sesko attribution: 1) either Sotheby's or Shinsa/Sesko were wrong in their attribution or 2) these are two different pieces, one - Kamakura-bori from the 14th century and another - Shōami from 16th/17th century. Anyway, I would consider my piece as a Shōami tsuba of Momoyama - early Edo period, just for the sake of modesty.

Iron tsuba of round form with design of lattice (kōshi-mon, 格子文) cut in openwork (sukashi), with low relief shallow linear carving along the bars. Well forged plate with brown-ish hue. To the right of nakago-ana there is a clear inscription of the character Shō (正), which is explained by Markus Sesko is follows: "The Shinsa obviously recognized more from the signature when having the tsuba in hand, i.e. they were confident to say it is signed "Shōami" but the rest is illegible (ika-fumei, 以下不明). That is, if they were just able to read the first character SHŌ (正) and saw that there were two more, most likely A (阿) and MI (弥), they would have put those character in boxes on the paper. Boxes around characters namely means that the character is not 100% legible but it can be assumed what it is." Momoyama or early Edo period. Dimensions: 85.9 mm diameter, 3.6 mm thickness at seppa-dai. Weight: 79 g. NBTHK certificate № 425069 with attestation: Hozon - "Worthy of preservation". A similar tsuba is presented at Japanese Sword Fittings from the R. B. Caldwell Collection. Sale LN4188 "HIGO". Sotheby's, 30th March 1994, №15. The description says: "A rare early Kamakura-bori tsuba. Nambokucho period (late 14th century). Of circular form, the dark plate carved and pierced with a gate design, the struts with double engraved lines. Unsigned. 8.5 cm." The lot was sold for 1,840 GBP.We have two possible explanations of the discrepancy between Sotheby's and Shinsa/Sesko attribution: 1) either Sotheby's or Shinsa/Sesko were wrong in their attribution or 2) these are two different pieces, one - Kamakura-bori from the 14th century and another - Shōami from 16th/17th century. Anyway, I would consider my piece as a Shōami tsuba of Momoyama - early Edo period, just for the sake of modesty.

Caldwell Collection. Sotheby's 1994, №15.

-

A ko-tosho tsuba made of iron, of the round form (丸型, maru-gata), pierced in negative silhouette (文透, mon-sukashi) with the design of Shingon Buddhism symbols of vajra [金剛杵] (kongosho), Sun, Moon and Star [月日星] (tsuki-hi-hoshi) – three sources of light [三光] (sankō). Round rim. No hitsu-ana; the shape of nakago-ana may suggest use on naginata [薙刀. Muromachi period (1393 – 1573). Height: 94.4 mm, Width: 93.4 mm, Centre thickness: 3.1 mm. Another possible explanation for "The element at the 11-o’clock position is in my opinion a kemari ball for the courtly game of the same name (picture attached)" [Markus Sesko].

A ko-tosho tsuba made of iron, of the round form (丸型, maru-gata), pierced in negative silhouette (文透, mon-sukashi) with the design of Shingon Buddhism symbols of vajra [金剛杵] (kongosho), Sun, Moon and Star [月日星] (tsuki-hi-hoshi) – three sources of light [三光] (sankō). Round rim. No hitsu-ana; the shape of nakago-ana may suggest use on naginata [薙刀. Muromachi period (1393 – 1573). Height: 94.4 mm, Width: 93.4 mm, Centre thickness: 3.1 mm. Another possible explanation for "The element at the 11-o’clock position is in my opinion a kemari ball for the courtly game of the same name (picture attached)" [Markus Sesko].

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi [月岡 芳年] (Japan, 1839 – 1892): Tokugawa Yoshimune [徳川 吉宗] (1684 – 1751) playing kemari [蹴鞠]

-

Iron tsuba of round form with design of military commander's fan (gunbai) in openwork (sukashi). Square rim. Hitsu-ana plugged with lead or tin. Ko-tosho school. Mid Muromachi period. Late 15th century: Entoku era [1489-92] / Meio era [1489-1501]. Height: 80.3 mm, Width: 81.5 mm, Rim thickness: 3.0 mm. Centre thickness: 3.5 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, №23 in Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994: Ko-tosho. Sukashi design: Military commander's fan (gunbai). Mid Muromachi period. Late 15th century (Entoku / Meio era). The military commander's fan (gunbai) was cherished by samurai warriors. This tsuba is relatively thick, with the large fan nicely positioned on the plate.

Iron tsuba of round form with design of military commander's fan (gunbai) in openwork (sukashi). Square rim. Hitsu-ana plugged with lead or tin. Ko-tosho school. Mid Muromachi period. Late 15th century: Entoku era [1489-92] / Meio era [1489-1501]. Height: 80.3 mm, Width: 81.5 mm, Rim thickness: 3.0 mm. Centre thickness: 3.5 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, №23 in Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994: Ko-tosho. Sukashi design: Military commander's fan (gunbai). Mid Muromachi period. Late 15th century (Entoku / Meio era). The military commander's fan (gunbai) was cherished by samurai warriors. This tsuba is relatively thick, with the large fan nicely positioned on the plate. -

Iron tsuba of round form with design of triple diamond (matsukawa-bishi) in openwork (sukashi). Square rim. Ko-Tosho school. Nanbokucho period: Late 14th century (Oan/Eiwa era). Height: 92.3 mm. Width: 92.3 mm. Rim thickness: 2.5 mm. Center thickness: 3.0 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 15: "Two small lozenges are attached to each end of a larger lozenge. Most Ko-tosho tsuba have inspirational designs, however this has a rather casual appearance, although it represents the unstable political situation at the time".

Iron tsuba of round form with design of triple diamond (matsukawa-bishi) in openwork (sukashi). Square rim. Ko-Tosho school. Nanbokucho period: Late 14th century (Oan/Eiwa era). Height: 92.3 mm. Width: 92.3 mm. Rim thickness: 2.5 mm. Center thickness: 3.0 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 15: "Two small lozenges are attached to each end of a larger lozenge. Most Ko-tosho tsuba have inspirational designs, however this has a rather casual appearance, although it represents the unstable political situation at the time". -

The chrysanthemoid (kiku-gata) iron plate with polished surface decorated with arabesque (karakusa) and paulownia (kiri) leaves and flowers in brass, copper and silver flush inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Some of the inlay goes over the edge. Kozuka- and kogai-hitsu-ana are filled with lead plugs. Sekigane of copper. Chrysanthemum and paulownia are the symbols of imperial family. The face is signed: Izumi no Kami to the right of nakago-ana, and Yoshiro on the left; the back is signed Koike Naomasa. His signed work is considered by many experts to have been made-to-order only. The original wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) signed by Dr. Kazutaro Torigoye and dated Showa 39 (1964). The late Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: 89 mm x 84 mm x 3.6 mm; Weight: 170 g. Hakogaki lid: Yoshirō kikka-gata Hakogaki lid inside: Iron, signed on the omote: Izumi no Kami – Yoshirō; on the ura: Koike Naomasa. Kikka-gata, pronounced maru-mumi, two hitsu-ana, karakusa, and kiri design in brass, silver, and suaka hira-zōgan. Height 8.5 cm, thickness 3.5 mm. Herewith I judge this work as authentic. On a lucky day in July of 1964. Torigoe Kōdō [Kazutarō] + kaō According to Robert Haynes [Catalog #7, 1983; №32, page 42-43] "This full form of the signature is seen very rarely". His example, illustrated in that catalogue, measures: height = 86 mm, thickness at seppa-dai = 3.75 mm and signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back and Koike Naomasa on the face. The further description of his specimen by Robert Haynes:

The chrysanthemoid (kiku-gata) iron plate with polished surface decorated with arabesque (karakusa) and paulownia (kiri) leaves and flowers in brass, copper and silver flush inlay (hira-zōgan) on both sides. Some of the inlay goes over the edge. Kozuka- and kogai-hitsu-ana are filled with lead plugs. Sekigane of copper. Chrysanthemum and paulownia are the symbols of imperial family. The face is signed: Izumi no Kami to the right of nakago-ana, and Yoshiro on the left; the back is signed Koike Naomasa. His signed work is considered by many experts to have been made-to-order only. The original wooden box (tomobako) with inscription (hakogaki) signed by Dr. Kazutaro Torigoye and dated Showa 39 (1964). The late Muromachi or Momoyama period, 16th century. Dimensions: 89 mm x 84 mm x 3.6 mm; Weight: 170 g. Hakogaki lid: Yoshirō kikka-gata Hakogaki lid inside: Iron, signed on the omote: Izumi no Kami – Yoshirō; on the ura: Koike Naomasa. Kikka-gata, pronounced maru-mumi, two hitsu-ana, karakusa, and kiri design in brass, silver, and suaka hira-zōgan. Height 8.5 cm, thickness 3.5 mm. Herewith I judge this work as authentic. On a lucky day in July of 1964. Torigoe Kōdō [Kazutarō] + kaō According to Robert Haynes [Catalog #7, 1983; №32, page 42-43] "This full form of the signature is seen very rarely". His example, illustrated in that catalogue, measures: height = 86 mm, thickness at seppa-dai = 3.75 mm and signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back and Koike Naomasa on the face. The further description of his specimen by Robert Haynes:"Early signed example of the work of Koike Naomasa. The kiku shape iron plate is well finished. The flush inlay is brass, for the scroll work on both sides, with the leaves and kiri mon in brass, copper and silver with strong detail carving. Some of the inlay goes almost over the edge, which is goishi gata. The large hitsuana are plugged in lead with starburst kokuin surface design. [...]The face is signed in deep bold kanji: Koike Naomasa; the back is signed: Izumi no Kami, on the right and Yoshiro on the left. There are one or two small pieces of inlay missing. Sold by Sotheby London, Oct. 27, 1981, lot 368. Height = 86 mm, thickness (seppa-dai) = 3.75 mm, (edge) = 4 mm."

Another similar example presented at: "Tsuba" by Günter Heckmann, 1995, №T55 — "Designation: Koike Naomasa. Mid Edo, end of the 17th century. Iron, hira-zogan in brass, copper, silver and shakudo, katakiri-bori. Tendrils and leaves. 87.0 x 78.0 x 4.0 mm." Reference: Japanische Schwertzierate by Lumir Jisl, 1967, page. 13. [SV: Actually, his tsuba is signed Izumi no Kami Yoshiro on the back; and Koike Naomasa on the front, exactly as Robert Haynes's tsuba. Dating this tsuba Mid-Edo, 17th century may be considered a misattribution]. More details regarding the Yoshirō tsuba. -

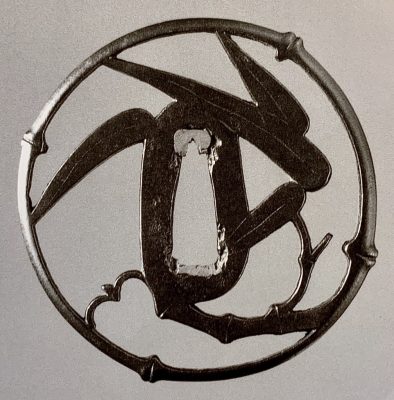

Kyo-sukashi iron tsuba of round form with design of hollyhock (aoi ) and wild geese. Slightly rounded rim. Copper sekigane. Momoyama period, late 16th - early 17th century. Height: 82.6 mm, Width: 82.1 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 4.5 mm. NTHK (Nihon Token Hozon Kai) certified.

Kyo-sukashi iron tsuba of round form with design of hollyhock (aoi ) and wild geese. Slightly rounded rim. Copper sekigane. Momoyama period, late 16th - early 17th century. Height: 82.6 mm, Width: 82.1 mm, Thickness at seppa-dai: 4.5 mm. NTHK (Nihon Token Hozon Kai) certified. -

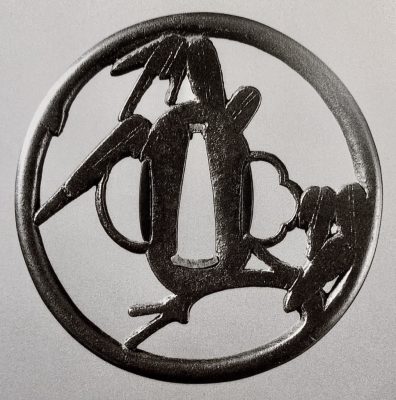

Iron tsuba of round form with design of water plantain (omodaka) and wild goose in openwork (sukashi). Slightly rounded, square rim. Copper sekigane. Kyo school. Late Muromachi period: Early 16th century (Tenbun era) [Sasano's attribution]. Height: 76.2 mm. Width: 75.8 mm. Rim thickness: 5.3 mm. Center thickness: 4.5 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 68: "The water plantain (omodaka) first appeared as a design for sword fittings in the Heian period. From such early beginnings, this decorative plant has shared a long history with the samurai. Also known as shogun's grass (shogununso), it was held in high esteem as a symbol of victory". The same tsuba was found at Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A. Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections. Sotheby's, London, Thursday 10 April 1997, page 22, item 60, saying that this is a "Kyo-sukashi tsuba, early to middle Edo period (late 17th/18th century) [Sotheby's attribution], and that it represents "a small bird among omodaka and aoi plants".

Iron tsuba of round form with design of water plantain (omodaka) and wild goose in openwork (sukashi). Slightly rounded, square rim. Copper sekigane. Kyo school. Late Muromachi period: Early 16th century (Tenbun era) [Sasano's attribution]. Height: 76.2 mm. Width: 75.8 mm. Rim thickness: 5.3 mm. Center thickness: 4.5 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 68: "The water plantain (omodaka) first appeared as a design for sword fittings in the Heian period. From such early beginnings, this decorative plant has shared a long history with the samurai. Also known as shogun's grass (shogununso), it was held in high esteem as a symbol of victory". The same tsuba was found at Japanese Swords and Tsuba from the Professor A. Z. Freeman and the Phyllis Sharpe Memorial collections. Sotheby's, London, Thursday 10 April 1997, page 22, item 60, saying that this is a "Kyo-sukashi tsuba, early to middle Edo period (late 17th/18th century) [Sotheby's attribution], and that it represents "a small bird among omodaka and aoi plants". -

Copper tsuba of slightly elongated round form carved in low relief (shishiaibori and sukisagebori) and inlaid in gold, silver and shakudō with the design of dreaming Rosei (Lu Sheng): he is half-sitting by the pillow with his eyes closed, holding his fan, with a scroll by his feet, surrounded by flying butterflies.

Edo period, first half of the 18th century.

Dimensions: 70.8 x 67.1 x 5.0 mm. Signed on the reverse: Jōi (乗 意) + Kaō. Sugiura Jōi [杉 浦 乗 意] (1701-1761) was a master of Nara School in Edo; he was a student of Toshinaga [M. Sesko, ‘Genealogies’, p. 32]. “Sugiura Jōi (1701-1761) made many fuchigashira and kozuka, tsuba are rather rare.” [M. Sesko, The Japanese toso-kinko Schools, pp. 148-149]. On Rosei (Lu Sheng) dream's legend see Legend in Japanese Art by Henri L. Joly (1908 edition) on page 293. -

Iron tsuba of quatrefoil form with design of bamboo stems and leaves, and a plank bridge in openwork (sukashi). Hitsu-ana of irregular form. Iron with smooth chocolate patina. Copper and shakudō sekigane. This piece is illustrated in Sasano: Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994 on page 295 under № 254 with the following description:

Iron tsuba of quatrefoil form with design of bamboo stems and leaves, and a plank bridge in openwork (sukashi). Hitsu-ana of irregular form. Iron with smooth chocolate patina. Copper and shakudō sekigane. This piece is illustrated in Sasano: Japanese Sword Guard Masterpieces from the Sasano Collection, 1994 on page 295 under № 254 with the following description:Nishigaki. First generation Kanshiro (died in the sixth year of Genroku, 1693, at the age of 81). Sukashi design: Bamboo (take). Early Edo period, late 17th century (Kanbun / Enppo era). Height: 72.6 mm; Width: 71.5 mm; Rim thickness: .6 mm; Centre thickness: 5.1 mm. Rounded rim. The shape of this sword guard is a quatrefoil and the design is arranged in the form of a saddle flap. Two bamboo trunks with leaves comprise the design. Calm, soothing and sophisticated are the features of this artist in his later years. Such characteristics may remind one of the work of the first Hikozo.

Provenance: Sasano Masayuki collection, № 254. What is interesting, and what had been found by Bruce Kirkpatrick, is that in the earlier photograph of the same piece ['Sukashi tsuba - bushido no bi' by Sasano Masayuki, photography by Fujimoto Shihara, 1972 (in Japanese), page 245, №201] we clearly see kebori - linear carving that decorates the bamboo leaves and the planks of the bridge. The said kebori have totally disappeared between 1972 and 1994. The tsuba became absolutely flat! Now we can only speculate about the reasons for such cruel treatment of the artistically and historically important item.

Sukashi tsuba - bushido no bi. Author: Sasano Masayuki, photography: Fujimoto Shihara, 1972 (in Japanese). Page 245, №201.

-

Iron tsuba of quatrefoil form with design of bamboo stems and leaves in openwork (sukashi) decorated with carving (kebori) . Copper sekigane. Early Edo period, late 17th century (Kanbun / Enppo era). First generation Kanshiro of Nishigaki school in Higo Province died in the sixth year of Genroku, 1693, at the age of 81). Height: 74.4 mm; Width: 74.2 mm; Centre thickness: 4.9 mm. Rounded rim. The design was quite popular among the Higo masters.

Iron tsuba of quatrefoil form with design of bamboo stems and leaves in openwork (sukashi) decorated with carving (kebori) . Copper sekigane. Early Edo period, late 17th century (Kanbun / Enppo era). First generation Kanshiro of Nishigaki school in Higo Province died in the sixth year of Genroku, 1693, at the age of 81). Height: 74.4 mm; Width: 74.2 mm; Centre thickness: 4.9 mm. Rounded rim. The design was quite popular among the Higo masters.

Kanshiro III, early 18th century (Sasano 1994 №267)

Matashichi I, late 17th century (Sasano 1994 №270)

The design of my tsuba closely resembles the one at the last example (Sasano 1994 №280), however, the form (mine is quatrefoil) and the execution (strength) are very different, which result in a very different spirit of my piece.

Shigemitsu II, early 18th century (Sasano 1994 №280)

-

Iron tsuba of oval form with design of stylized paulownia (nage-giri) in openwork (sukashi). Leaf veins carved in kebori technique. Rounded rim. Copper sekigane. Unsigned. Attributed to Kanshirō, third generation Nishigaki (1680-1761). Edo period: Early 18th century (Kyoho / Genbun era). Size: Height: 77.8 mm. Width: 71.9 mm. Rim thickness: 5.9 mm. Center thickness: 5.0 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 264: "Nishigaki. Third generation Kanshiro (died in in the eleventh year of Hohreki, 1761 at the age of eighty-two). This oblong shape appears a little amateurish at first, however, it was done intentionally to add flavor to to the design. The neat composition is a feature of the third Kanshiro."

Iron tsuba of oval form with design of stylized paulownia (nage-giri) in openwork (sukashi). Leaf veins carved in kebori technique. Rounded rim. Copper sekigane. Unsigned. Attributed to Kanshirō, third generation Nishigaki (1680-1761). Edo period: Early 18th century (Kyoho / Genbun era). Size: Height: 77.8 mm. Width: 71.9 mm. Rim thickness: 5.9 mm. Center thickness: 5.0 mm. Provenance: Sasano Masayuki Collection, № 264: "Nishigaki. Third generation Kanshiro (died in in the eleventh year of Hohreki, 1761 at the age of eighty-two). This oblong shape appears a little amateurish at first, however, it was done intentionally to add flavor to to the design. The neat composition is a feature of the third Kanshiro." -

Iron tsuba of mokko form decorated with encircled family crests in low relief carving; niku from 3.0 mm in the centre to 4.0 mm at rim and full 1 mm raised uchikaeshi-mimi. Nobuie [信家] signature (hanare-mei) to the left of nakago-ana; on the reverse, to the right of nakago-ana, the inscription reads “62”, which may be how old the master was at the age of making the tsuba. Pewter or lead plugged hitsuana. In a wooden box, in a custom pouch. Size: H: 80 mm, W: 75, Th(c): 3.1 mm, Th(r): 4.0 mm Weight: 103.5 g

Iron tsuba of mokko form decorated with encircled family crests in low relief carving; niku from 3.0 mm in the centre to 4.0 mm at rim and full 1 mm raised uchikaeshi-mimi. Nobuie [信家] signature (hanare-mei) to the left of nakago-ana; on the reverse, to the right of nakago-ana, the inscription reads “62”, which may be how old the master was at the age of making the tsuba. Pewter or lead plugged hitsuana. In a wooden box, in a custom pouch. Size: H: 80 mm, W: 75, Th(c): 3.1 mm, Th(r): 4.0 mm Weight: 103.5 gSigned: Nobuie [信家] / 62

Probably the work of Shodai Nobuie (c. 1580).

Tokubetsu hozon certificate № 2002993 of the N.B.T.H.K., dated January 15, 2016. NOBUIE TSUBA by Steve Waszak The iron tsuba made by the two early Nobuie masters are regarded as the greatest sword guards ever made across hundreds of years of Japanese history. Only a small handful of other smiths' names are even mentioned in the same breath as that of Nobuie. Despite the well-deserved fame of the Nobuie name, virtually nothing is known with certainty about the lives of the two men who made the pieces carrying this name. They are thought to have been men of Owari Province, with the Nidai Nobuie also spending time in Aki Province at the end of the Momoyama Period. Two Nobuie tsubako are recognized. The man whom most consider to have been the Shodai signed his sword guards with finer and more elegantly inscribed characters than the smith seen by most as the Nidai. The term used to describe the mei of the Shodai is "hanare-mei" or "ga-mei," while that used to characterize the signature of the Nidai is "futoji-mei" or "chikara-mei." These terms refer to the fineness and grace of the Shodai's signature and the relatively more powerfully inscribed characters of the Nidai's. The Shodai is thought to have lived during the Eiroku and Tensho eras in the latter part of the 16th century, while the Nidai's years are considered to have been from Tensho into the Genna era. This locates both smiths well within the Golden Age of tsuba artists -- the Momoyama Period. Nobuie tsuba are esteemed and celebrated for the extraordinary beauty of their iron. The combination of the forging of the metal, the surface treatment by tsuchime and yakite married to powerfully expressive carving, the masterful manipulation of form, mass and shape, and the colour and patina of the iron makes Nobuie sword guards not only unique in the world of tsuba, but the greatest of the great. The sword guard here is a Shodai-made masterwork, done in mokko-gata form, a shape the early Nobuie smiths mastered to a degree unmatched by any others. The expanding of the mass of the tsuba from the seppa-dai to the mimi, increasing by 50% from the centre of the guard to the rim, creates a sense of exploding energy, which is then contained by the uchikaeshi-mimi, yielding a lightning-in-a-bottle effect of captured energy. The hammering the master has employed to finish the surface is subtle and sensitive, achieving a resonant profundity, and the deep blue-black colour -- augmented by a lustrous patina -- leaves the tsuba to positively glow in one's hand. In this piece, Nobuie has used a motif of several kamon, or family crests, each carved only lightly on the surface in a loose ring around the nakago-ana. Due to the shallow depth of this carving, together with the tsuchime finish of the plate, the effect is to leave the kamon with a sort of weathered appearance, recalling the prime aesthetic values of sabi and wabi, which had great circulation in the Tea Culture so ascendant in the Momoyama years. However, the effects of sabi and wabi expressed in the treatment described above are amplified and deepened by the color and patina of the iron, thereby adding yet another aesthetic value -- yuugen -- which is linked with the abiding mystery of the universe and one more — mono no aware — which alludes to the pathos of life's experiences and transitory nature. In short, this Nobuie tsuba joins poetry with power and therein exemplifies the unrivalled brilliance of Nobuie workmanship. -

Iron tsuba of mokko form decorated with arabesque (karakusa) in low relief carving. niku from 4.0 mm in the centre to 5.1 mm at the rim. Strong Nobuie [信家] signature (futoji-mei) to the left of nakago-ana. Hitsuana plugged with pewter.

Size: H: 88.2 mm, W: 83.6, Th(c): 4.0 mm, Th(r): 5.1 mm Weight: 167 g.Signed: Nobuie [信家]

Probably the work of Nidai Nobuie (c. 1600).

Tokubetsu hozon certificate № 229324 of the N.B.T.H.K., dated 22.12.2010 -

Iron tsuba in a form of an eight-petalled blossom (lotus) form, petals separated by linear low-relief carving, both hitsu-ana filled with gold plugs, the surface decorated with tsuchime-ji, rich grey-brownish patina, niku from 4 mm in the centre to 6 mm at the rim. Strong (futoji-mei) Nobuie [信家] signature to the left of nakago-ana. Attributed to the 2nd generation of Nobuie masters (Nidai Nobuie).

Size: outer diameter 84 mm, thickness at centre: 4 mm, at rim: 6 mm. Wight: 167 g.Signed: Nobuie [信家]

Probably the work of Nidai Nobuie (c. 1600).

The gold plugs are likely a later work. -

Iron tsuba of mokkō-form with a pine and a frog on the face and a snail on the back, carved and inlaid with gold. Each figurative element of the design is signed on three inlaid cartouches: Masaharu (正春), Kazuyuki (一之), and Yoshikazu (良一) [read by Markus Sesko]. Snake, snail, and frog together make a design called "SANSUKUMI" - Three Cringing Ones [Merrily Baird]. The snail can poison the snake, the frog eats the snail, and the snake eats the frog. It's unclear whether the pine replaces the snake on this tsuba, or the snake is hiding in the pine? Anyway, the frog and the snail are clearly represented. "Maybe we have here a joint work with Masaharu (the silver cartouche next to the pine) being the master and making the plate and Kazuyuki and Yoshikazu as his students carving out the frog and the snail respectively". Copper sekigane.

Dimensions: 70.9 x 67.2 x 3.0 mm. Edo period (18th century).Markus Sesko writes: "I agree, the frog and the snail most likely allude to the san-sukumi motif. It is possible that we have here an artist's choice to deliberately leave out the snake, maybe he thought that the motif is already obvious and there is no need to add a snake to make it clear that the tsuba shows the san-sukumi motif." [Markus Sesko].

Kazuyuki (一之): adopted son of Kumagai Yoshiyuki, student of Ichijō (Gotō-Ichijō Scool) [M. Sesko 'Genealogies', page 19.] Masaharu (正春): Kasuya fam., student of Masamichi (1707-1757) who was the 4th generation Nomura School master in Edo. [M. Sesko 'Genealogies', page 49.] -

Large iron tsuba with hammer marks on the surface, small oval opening to the right of nakaga-ana; yamagane fukurin chiselled with tortois shell diaper pattern.

Early Muromachi period (1393-1453). Size: 101.2 x 101.9 x 2.4 (center), 5.2 (rim) mm; weight: 148.4 g. -

Iron tsuba of a round form (maru-gata) pierced (sukashi) with two six-petal flowers at 6 and 12 o’clock and modified lozenges at 3 and 9 o’clock, and inlaid in brass (suemon-zōgan) with tendrils and flowers (chrysanthemum, cherry blossom, Chinese bellflower, paulownia); openings outlined with scalloped brass wire. The plate is slightly concave with traces of lacquer on the surface. Nakago-ana plugged with copper sekigane. Some elements of inlay missing. The rim with conspicuous tekkotsu, quite worn. Measurements: Height 92.0 mm; Width 86.3 mm; thickness at seppa-dai 3.2 mm, at rim 4.2 mm. Time: Late Muromachi (1514 – 1573) or earlier.

Iron tsuba of a round form (maru-gata) pierced (sukashi) with two six-petal flowers at 6 and 12 o’clock and modified lozenges at 3 and 9 o’clock, and inlaid in brass (suemon-zōgan) with tendrils and flowers (chrysanthemum, cherry blossom, Chinese bellflower, paulownia); openings outlined with scalloped brass wire. The plate is slightly concave with traces of lacquer on the surface. Nakago-ana plugged with copper sekigane. Some elements of inlay missing. The rim with conspicuous tekkotsu, quite worn. Measurements: Height 92.0 mm; Width 86.3 mm; thickness at seppa-dai 3.2 mm, at rim 4.2 mm. Time: Late Muromachi (1514 – 1573) or earlier. -

Iron tsuba of quatrefoil form (mokka-gata) adorned with the design of stars, wild geese, blossoms, leaves and tendrils realized in the brass inlay. The inlay technique includes suemon-zōgan and ten-zōgan. A smaller opening (kozuka hitsu-ana) surrounded by a scalloped brass border. The seppa-dai bordered with linear inlay. A few dots of inlay on both sides are missing. Measurements: height 71 mm, width 70 mm, thickness at centre 2.7 cm Time: Late Muromachi (1514 – 1573)